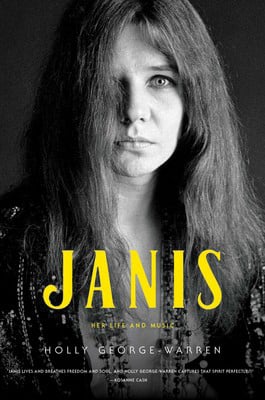

Texas-born rock icon Janis Joplin has been one of American culture’s most compelling figures for more than 50 years, in large part because of the intrigue she presents: Just who was this storm of a singer, and just what inside her came out as that voice? In Janis: Her Life and Music, author and music journalist Holly George-Warren makes a definitive exploration of those questions, laying out in impressive detail the particular personal alchemy that led Joplin to forge all-new alloys of power and vulnerability, freedom and fatalism.

Enabled by dozens of interviews and access to key archives, including the Joplin family’s, George-Warren achieves the assured voice of a biographer who knows her subject as well as anyone can. She chronicles every verifiable event and significant relationship in Joplin’s life so thoroughly, and quotes Joplin so thoughtfully, that when occasionally she allows herself a bit of speculation—Joplin “must have” or “might have”—it feels earned and insightful. And when the story reaches its sad end, George-Warren’s previous explanations of why Joplin used drugs—alcohol since her teen years, later speed, and by the end heroin—make the singer’s overdose death at 27 seem almost inevitable.

The book paints a portrait of an outsider whose thirst for acceptance was denied in her hometown of Port Arthur, then briefly satisfied by the 1950s and ’60s musical counterculture that embraced her in Austin and San Francisco. As her fame rose, though, the resultant scrutiny inflamed her core insecurities afresh. George-Warren makes clear Joplin’s competing desires: the picket-fence life that would have pleased her quite conventional mother versus the seeking, footloose path she first envisioned at age 14 upon reading Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. There are expected scenes among the beatniks, vagabonds, and hippies of Austin and San Francisco. But we also see Joplin sewing a quilt in traditional preparation for marriage. (Her engagement at age 22 to a philandering liar, with whom she’d fallen in love while using amphetamines on her first trip to California, ended with his abandonment and her first major heartbreak.) She plays golf with her aunt, adopts a puppy, and asks for a Betty Crocker cookbook for Christmas. The brash, flashy stage persona she developed and named Pearl, also the title of her final album, was more than just an act but less than the whole her.

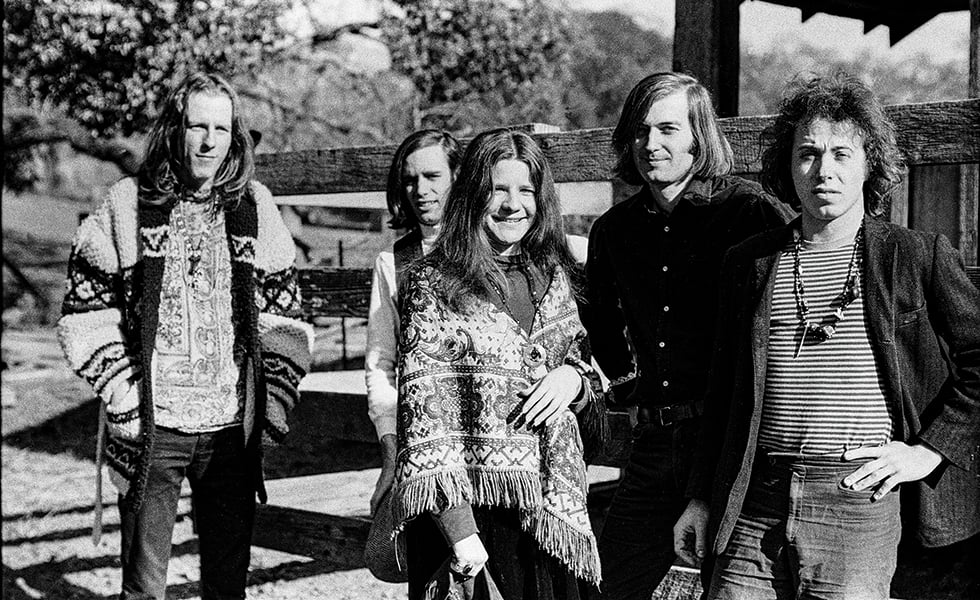

George-Warren is as attentive to Joplin’s musical influences and development as to the narrative of her life. The “swamp rock” acts of Southeast Texas and Southwest Louisiana—which attracted a rebellious, beer-swilling, teenage Joplin and her friends—are brought to life for readers unfamiliar with the somewhat obscure subgenre. George-Warren explains Joplin’s relationships with the performers she idolized, including blues singer Bessie Smith and Otis Redding. Both had a direct effect on Joplin’s stylistic choices as a singer. The book vividly depicts the various scenes that shaped her: the student music culture around the University of Texas at Austin, the ’60s folk revival in California and New York City, and the Haight-Ashbury hippie culture in San Francisco, where she would finally gain fame as a rock singer with Big Brother and the Holding Company and the band’s landmark album, Cheap Thrills.

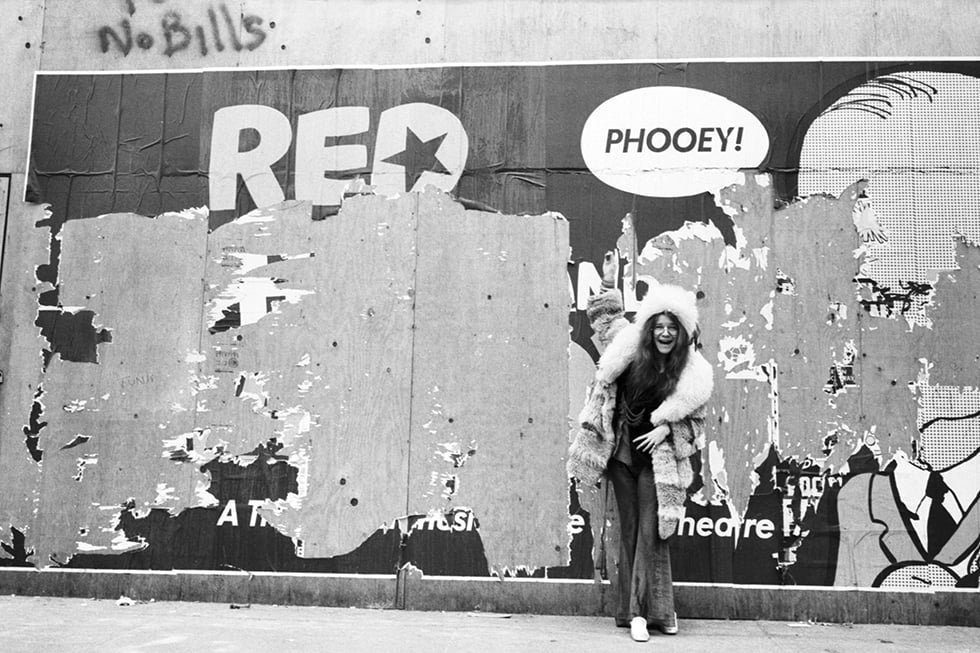

Joplin’s physicality is also a focus throughout the book, and it’s an emphasis entirely appropriate for a singer whose gutsy voice with its full-throated screeches was one of the most corporeal imaginable. Beginning with a childhood “tomboy” phase and continuing through her embrace of a beatnik aesthetic in high school, an infamous UT incident when she was nominated as the Ugliest Man on Campus, and beyond, Joplin’s bohemian appearance and style were among her most intense self-esteem dramas. George-Warren not only keeps tabs on the evolution of Joplin’s looks, but also provides insights into their meanings and contexts. Commenting on a letter home in which Joplin describes Summer of Love fashion (“capes of all kinds … boots, always boots”), George-Warren notes how Joplin’s wardrobe melded the influences of a roommate, of Smith’s beaded gowns and feathered hats, and of country singer Rose Maddox’s spangled costumes.

The author offers less analysis but plenty of particulars regarding Joplin’s voracious, omnivorous sexuality. New characters frequently arrive in the narrative with a variation on “with whom Janis would briefly share her bed,” and by the time George-Warren mentions in an arch aside Joplin’s tryst with pro quarterback Joe Namath, it’s hardly surprising. A few relationships, such as a yearlong affair with musician Joseph Allen “Country Joe” McDonald, stand out as more significant and serve as further markers of Joplin’s essential inner complexity. Even as Joplin sought free love with partners of various genders, she continually returned to her desire for a lasting “old man” from whom she could get the reliable, unconditional approval she felt only onstage. In an especially heartbreaking note, George-Warren points out that a long-awaited letter from the last of these loves was unopened in her mailbox as Joplin died on October 4, 1970.

As the narrative moves forward, George-Warren increases its granularity, zooming in to day-by-day and eventually hour-by-hour accounts of events as if, knowing the end is near, she seeks to hang on to her subject as long as possible. The denouement is unsatisfying in its brevity; George-Warren earns the prerogative to venture more commentary on Joplin’s legacy, and doing so would have helped readers frame the often-dizzying story she spins. But in view of the book’s skillful structuring and pacing, that’s a quibble.

A central theme in the book is an idea Joplin called the kozmic blues (and her cerebral, atheist father called the Saturday Night Swindle): a conviction that, as she put it, “no matter what you do, you get shot down anyway … it ain’t never gonna be all right—there’s always something going wrong.” Whether that’s a self-contained truth she discovered or a self-fulfilling truth she created, it’s a fitting lens through which to view a singer who was most famous for the line “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.” Joplin’s story embodies a life and an artistry embraced in full knowledge of—yet despite—its inevitable disappointments, shortcomings, and pain. Like Joplin herself, Janis delivers the most thrilling sort of pathos.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Mr. Reynolds’ Opus: How Graham Reynolds became Texas’ top composer.

-

Up From the Desert: As a child, I hunted for fossils in the Chihuahuan Desert beyond my backyard. Those afternoons shaped the way I think about my fronteriza identity today.

-

Michael Quinn Sullivan’s Recorded Conversation with Speaker Bonnen Exposes the Texas GOP for What It’s Always Been: The secret recording confirms the cynicism, vindictiveness, and ugliness at the heart of the Republican politics.