The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has found evidence of two giant asteroids slamming into each other in a nearby star system. The colossal collision ejected 100,000 times more dust than the impact that killed the dinosaurs.

The violent impact occurred recently in Beta Pictoris, a star system located 63 light-years away in the constellation Pictoris.

Beta Pictoris is a baby compared to our own solar system — having existed for only 20 million years compared with our system's venerable 4.5 billion years. It was first detected in 1983 by NASA's Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) spacecraft and is thought to have formed from the shockwave of a nearby supernova.

While the young star system currently contains at least two gas giant planets it has no known rocky worlds like our own. But rocky inner planets may be in the process of forming, thanks to large dust-producing collisions like the one spotted by JWST, the researchers behind the new findings said in a June 10 presentation at the 244th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Madison, Wisconsin.

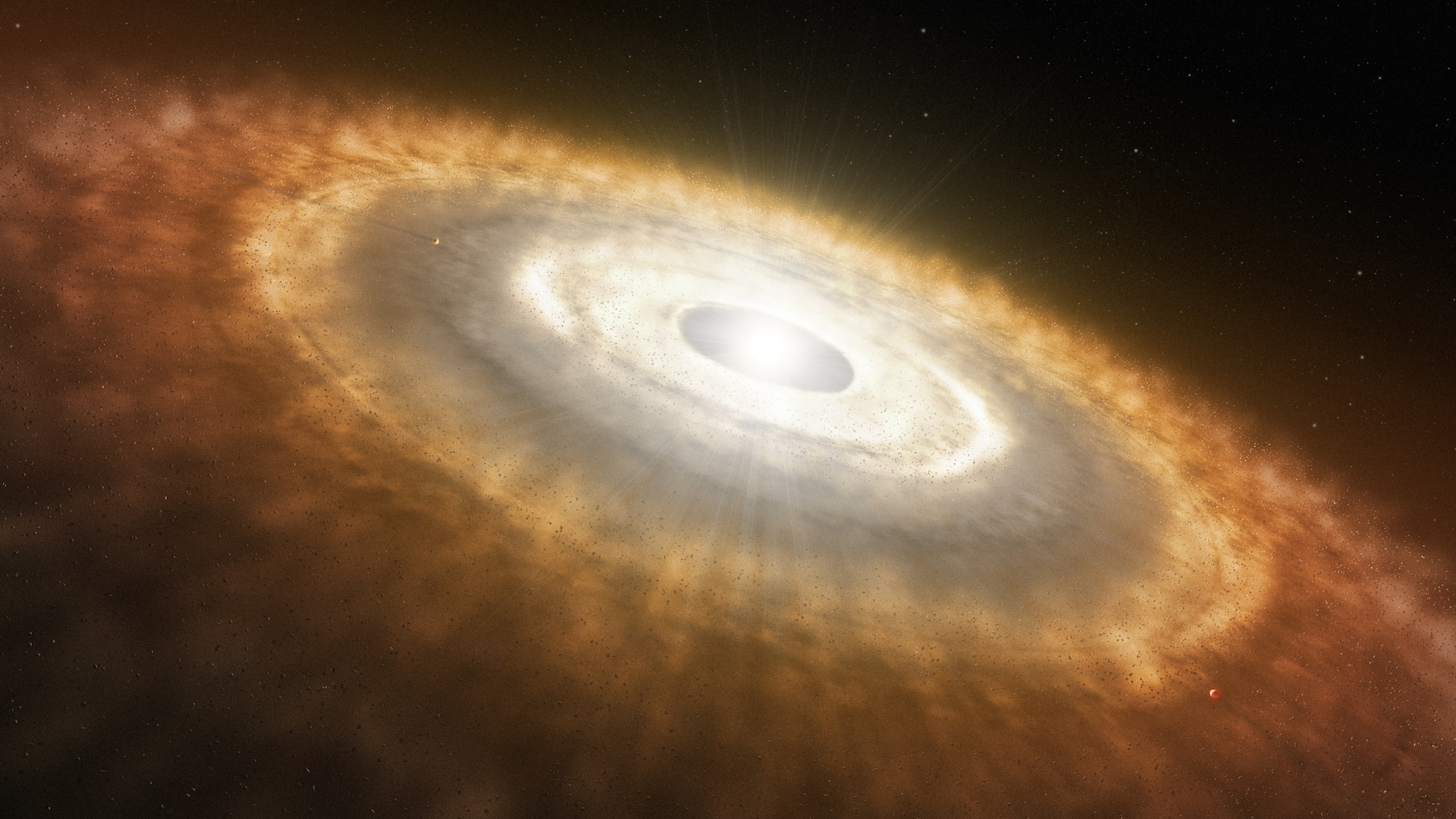

Because it is still very young, the star system's circumstellar debris disk — the vast ring of gas and dust surrounding the star — is a significantly more violent place than our own, making it the perfect place for astronomers to study the tumultuous early years of planet-forming systems. The team added that their findings could offer a rare insight into the history of our own solar system.

"Beta Pictoris is at an age when planet formation in the terrestrial planet zone is still ongoing through giant asteroid collisions, so what we could be seeing here is basically how rocky planets and other bodies are forming in real time," lead study author Christine Chen, an astronomer at Johns Hopkins University, said in a statement.

Related: James Webb telescope spots wind blowing faster than a bullet on '2-faced planet' with eternal night

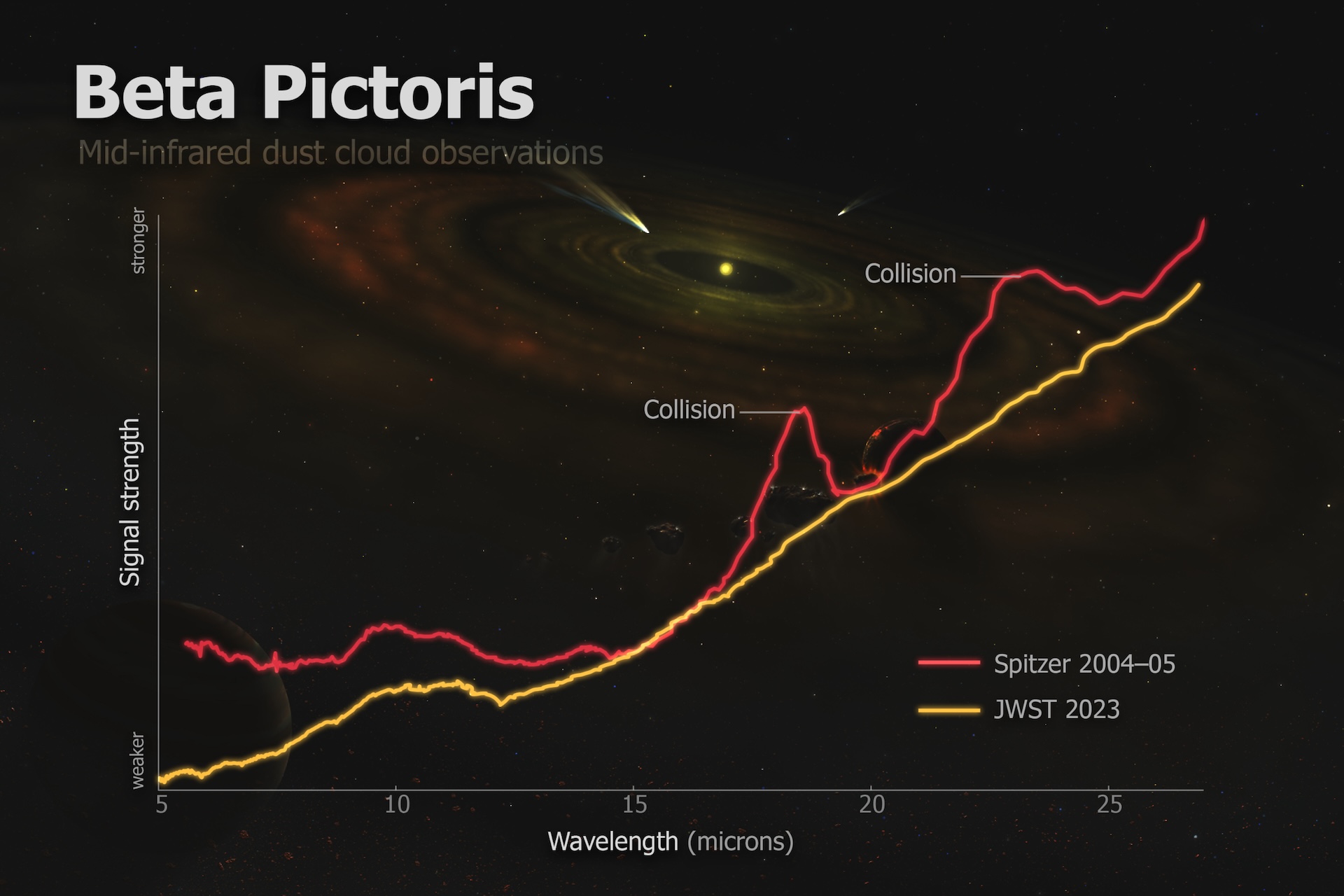

To capture a snapshot of the distant asteroid crash, the astronomers trained JWST's powerful eye on the system and found that giant masses of clumped silicate dust spotted by the Spitzer Space Telescope between 2004 and 2005 had completely disappeared.

This means that, sometime 20 years ago, a gigantic collision between two asteroids likely occurred, pounding the bodies into vast quantities of dust with particles smaller than pollen or powdered sugar, Chen said.

"With Webb's new data, the best explanation we have is that, in fact, we witnessed the aftermath of an infrequent, cataclysmic event between large asteroid-size bodies, marking a complete change in our understanding of this star system," Chen said.

The researchers suggest their findings will help astronomers to better understand how the architecture of star systems is constructed, and how often habitable systems like our own come into being.

"The question we are trying to contextualize is whether this whole process of terrestrial and giant planet formation is common or rare, and the even more basic question: Are planetary systems like the solar system that rare?" study co-author Kadin Worthen, a doctoral student in astrophysics at Johns Hopkins University, said in the statement. "We're basically trying to understand how weird or average we are."