Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) may have identified the smallest star in the known universe — or at least, the smallest known object that began forming like a star, before fizzling out as a so-called brown dwarf.

"One basic question you'll find in every astronomy textbook is, what are the smallest stars?," Kevin Luhman, an astronomer at Pennsylvania State University and lead author of a new paper on the strange object, said in a statement. "That's what we're trying to answer."

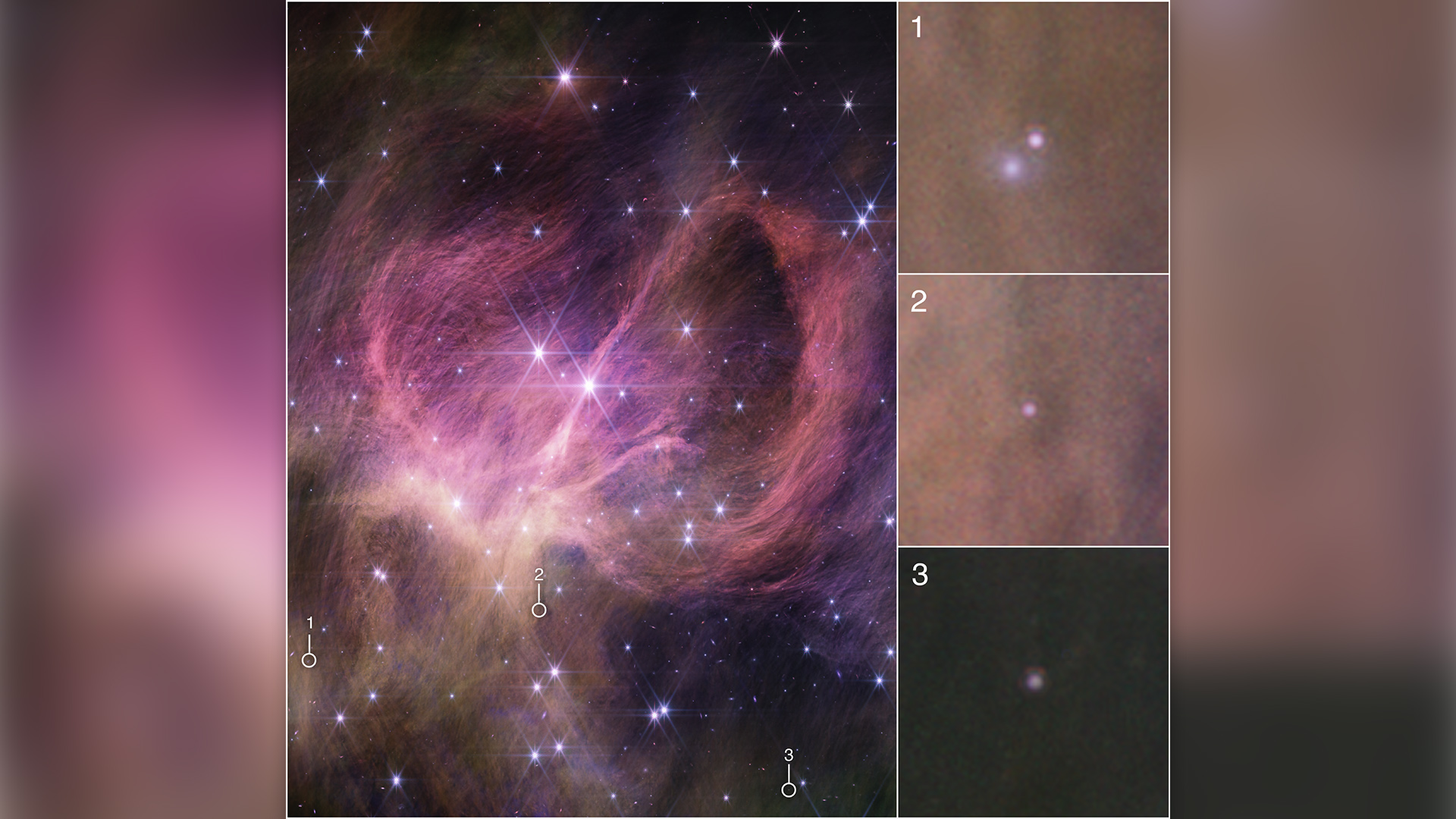

Using the JWST, Luhman and his team spotted the tiny proto-star in a star cluster named IC 348, which is located 1,000 light-years from Earth. The object is likely to be a brown dwarf, a type of celestial object that blurs the line between planet and star. The researchers published their findings on Dec. 13 in the Astronomical Journal.

Brown dwarfs are not quite stars, but they come close. Essentially, they are stars that failed to ignite, earning them the unflattering nickname "failed stars." Brown dwarfs are not massive enough to sustain typical hydrogen fusion in their cores. However, they do have enough mass to emit light and heat from fusing a specialized type of hydrogen, called deuterium. Deuterium is a stable form of hydrogen with an added neutron, whereas normal hydrogen only has a proton in its nucleus.

Related: What's the largest planet in the universe?

Most stars are incredibly dense compared to even the biggest planets; our own sun is about 1,000 times the mass of Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system, but its diameter is only 10 times that of Jupiter, according to NASA. In comparison, a large brown dwarf could pack about 80 Jupiters inside. But this particular brown dwarf is only three or four times more massive than Jupiter — easily making it the smallest "star," or star-like object, ever discovered. It is also very young; the star cluster that it belongs to is just 5 million years old.

In addition to being minuscule, the brown dwarf and its neighbors appear to have an intriguing molecule floating around in their atmospheres, the team found. The researchers detected a spectral signature from an unidentified hydrocarbon, a molecule that contains some of the raw ingredients for life as we know it. NASA's Cassini probe detected the same molecular signature in the atmosphere of Saturn's moon Titan, but this is the first time it has been seen outside of the solar system.

"Models for brown dwarf atmospheres don't predict its existence," study co-author Catarina Alves de Oliveira, an astronomer at the European Space Agency, said in the statement. "We're looking at objects with younger ages and lower masses than we ever have before, and we're seeing something new and unexpected."

Taken together, these observations could help researchers paint a clearer picture of how stars form — and how they fail. The researchers hope that future work will reveal even smaller stellar objects, as well as any tiny true stars that may be hiding nearby.