Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have observed a supermassive black hole in the early universe that is killing its galaxy by starving it to death. Remarkably, this "galactic death by starvation" seems to have proceeded very quickly thanks to the creation of 2 million miles per hour winds of gas.

Galaxies are considered "dead" or "quiescent" when their star formation has been cut off. This can happen when the building blocks of stars, dense clouds of gas and dust, have been exhausted. Scientists have long suspected that galaxies can be "killed" prematurely by their central supermassive black holes "purging" them of gas and dust.

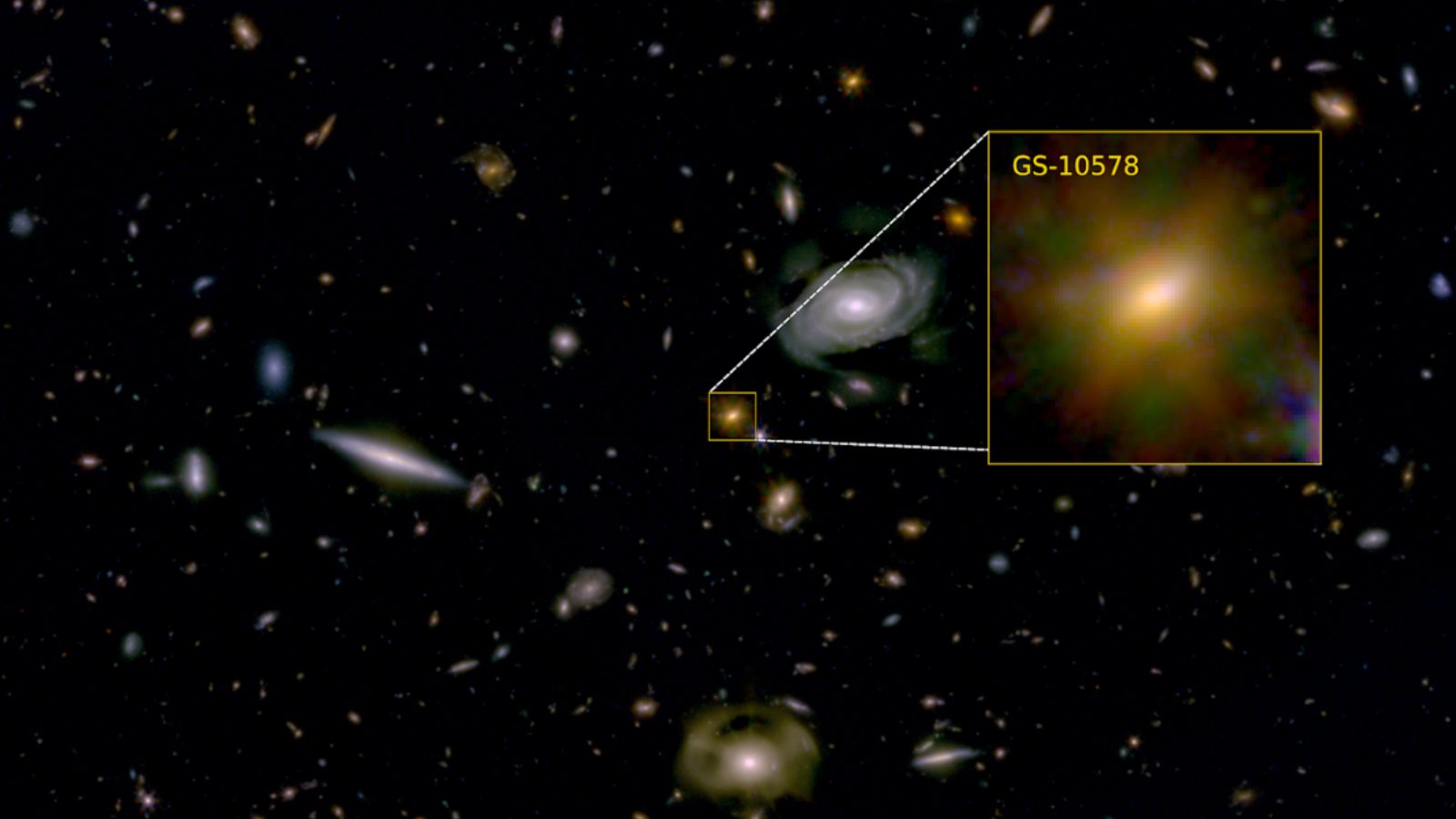

These JWST observations represent the first solid detection of such an effect and can indeed quench star birth by starving galaxies. The findings were delivered by a team of researchers led by University of Cambridge scientists who studied the early galaxy officially named GS-10578 but nicknamed "Pablo’s Galaxy" after the team member who proposed to observe it in detail.

Pabalo's galaxy is located around 11.5 billion light-years away, meaning it is seen as it was just 2.3 billion years or so after the Big Bang.

"Based on earlier observations, we knew this galaxy was in a quenched state: it's not forming many stars given its size, and we expect there is a link between the black hole and the end of star formation," team member Francesco D’Eugenio from Cambridge's Kavli Institute for Cosmology said in a statement. "However, until the JWST, we haven't been able to study this galaxy in enough detail to confirm that link, and we haven't known whether this quenched state is temporary or permanent."

Related: How do supermassive black holes 'starve' their galaxies to halt star formation?

With a mass 200 billion times that of the sun, the roughly Milky Way-sized galaxy that birthed most of its stars between 12.5 billion and 11.5 billion years ago is unusually massive for this period in the early universe.

"In the early universe, most galaxies are forming lots of stars, so it's interesting to see such a massive dead galaxy at this period in time," team member Roberto Maiolino, also from the Kavli Institute for Cosmology, said. "If it had enough time to get to this massive size, whatever process that stopped star formation likely happened relatively quickly."

Using the JWST, the team was able to determine that the supermassive black hole at the heart of Pablo’s Galaxy is pushing vast amounts of gas away at speeds as great as 2.2 million miles per hour. For context, that is 1,500 times as fast as the top speed of a Lockheed Martin F-16 jet fighter.

The speed of the gas is significant because it is substantial enough to defeat the gravitational influence of Pablo's galaxy and thus escape the galaxy for good.

Many galaxies with feeding or "accreting" supermassive black holes have rapid winds of gas flowing from them, but normally, these are of quite low mass. The JWST found a new component in the winds of Pablo's Galaxy that other telescopes have missed around other active galaxies.

This dense gas component is cooler and denser and thus emits little light which is why other telescopes didn't see it. The JWST, with its incredible sensitivity, was able to detect this dense gas stream because it is blocking light from galaxies behind it.

The team found that the mass of the gas stream from Pablo's Galaxy was greater than the gas needed to form the basis of the new star formation. This is enough to show that this galaxy's supermassive black hole is quenching star birth in this distant and early galaxy.

"We found the culprit," D’Eugenio said. "The black hole is killing this galaxy and keeping it dormant by cutting off the source of 'food' the galaxy needs to form new stars."

While the JWST observations confirmed prior models of galactic evolution and the role of supermassive black holes in quenching star birth, they did deliver some surprises.

Previously, theoretical models predicted the end of star formation could have a chaotic and turbulent effect on galaxies, destroying their shape. The fact that the stars in Pablo's Galaxy seem to still be moving in an orderly way hints that this might not always be the case.

The team now intends to follow up on the JWST observations of Pablo's Galaxy with an investigation conducted using the Atacama Large Millimeter-Submillimeter Array (ALMA), which consists of 66 radio telescopes located in Northern Chile. This could reveal if any cool, dense gas remains in Pablo's Galaxy and the effect its supermassive black hole is having on the galaxy's immediate surroundings.

"We knew that black holes have a massive impact on galaxies, and perhaps it's common that they stop star formation, but until the JWST, we weren't able to directly confirm this," Maiolino concluded. "It's yet another way that the JWST is such a giant leap forward in terms of our ability to study the early universe and how it evolved."

The team's research was published on Monday (Sept. 16) in the journal Nature Astronomy.