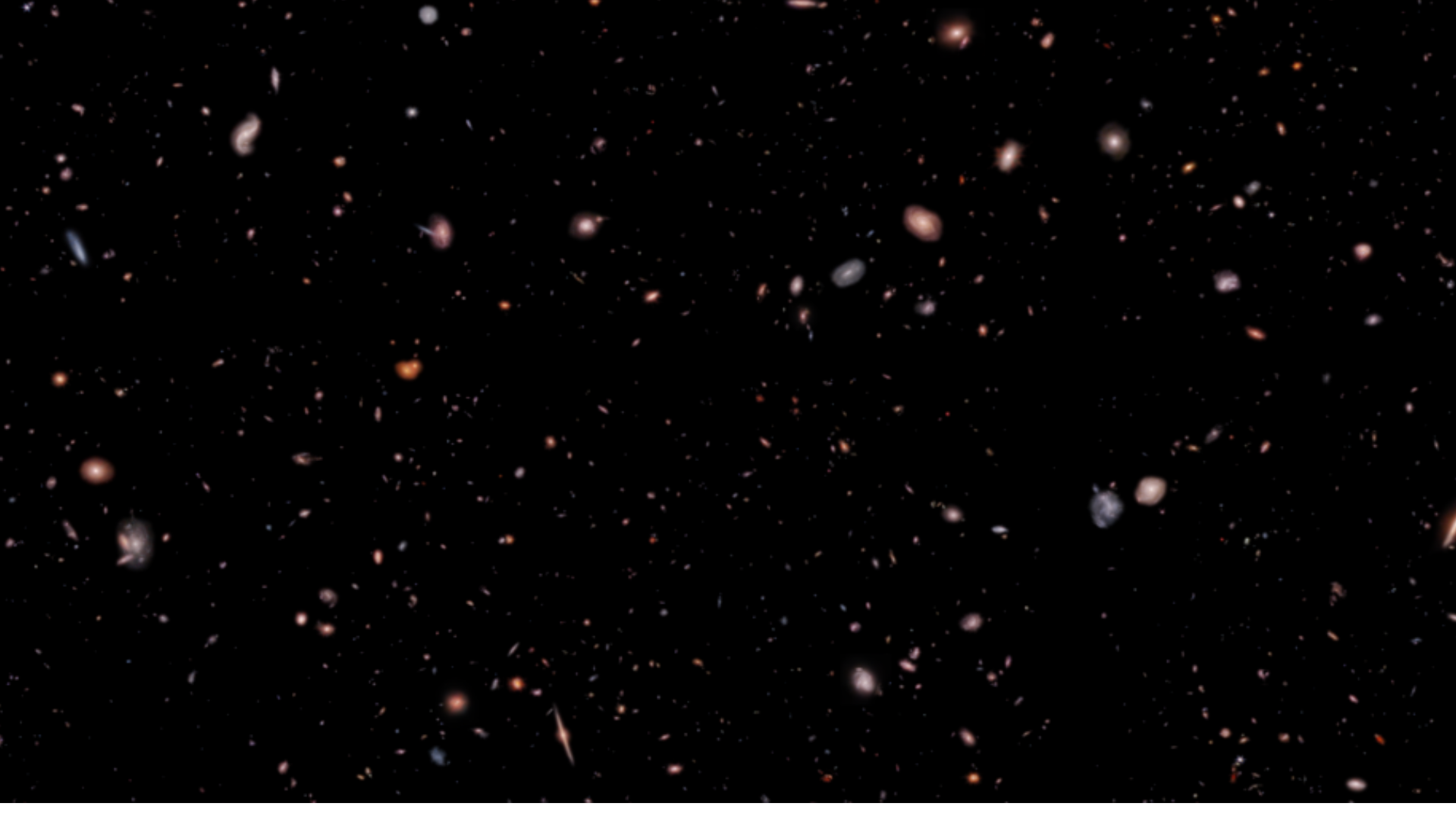

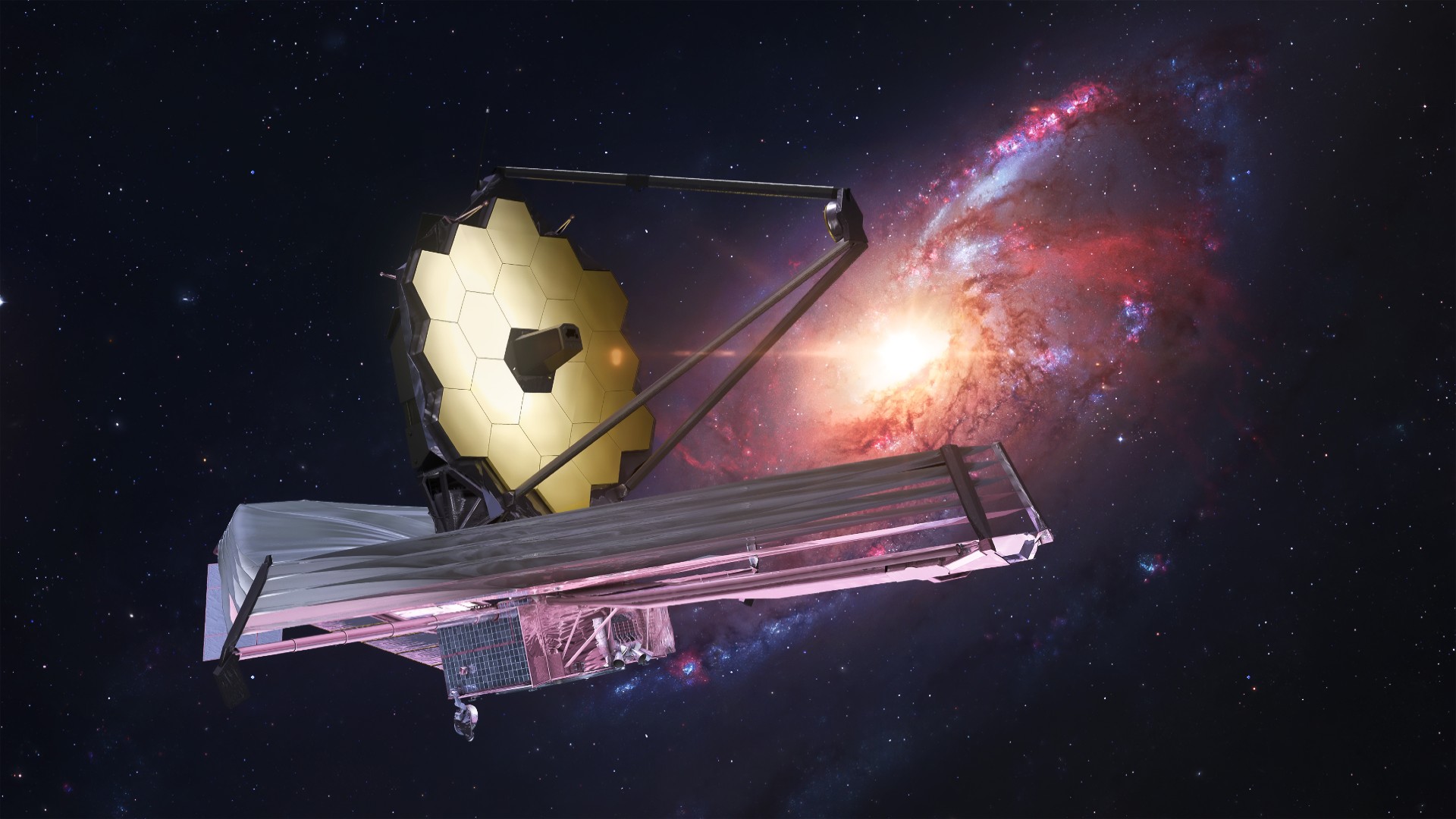

A new 3D visualization from the James Webb Space Telescope takes viewers on a journey back in time to just after the Big Bang.

In the video, over 5,000 galaxies can be seen in gorgeous full color and three dimensions. The cosmic journey begins with relatively nearby galaxies located within a few billion light-years of Earth and concludes at Maisie's Galaxy, which at 13.4 billion light-years from Earth is one of the most distant galaxies ever observed by humanity and is seen as it was just around 390 million years after the Big Bang.

As such, this new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) video doesn't just represent a journey through space but also a trip back through time, rewinding cosmic evolution back to a period when the 13.8 billion-year-old universe was under a third of its current age.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope spots violent collision between neutron stars

The video is the result of data collected by the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey (CEERS) and explores a region of space called the Extended Groth Strip. The Extended Groth Strip is located between the constellations of Ursa Major and Boötes and contains around 100,000 galaxies. It was extensively imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope between 2004 and 2005, and the new observations by the JWST build on the groundwork laid by Hubble.

Of particular interest to astronomers in this visualization is Maisie's Galaxy, serving as an example of the kind of early galaxy that the JWST is capable of studying. The powerful space telescope does this by observing the universe in infrared.

This is useful because as light from early galaxies travels billions of years to reach us, the expansion and the universe and the fact that it loses energy causes its wavelength to "stretch." This results in electromagnetic radiation that left the galaxies shortly after the Big Bang as optical light being "redshifted" down the electromagnetic spectrum past the red end of the visible light spectrum to infrared. The longer the light has traveled, the more extreme the redshift it experiences, making infrared the best way to see early galaxies.

"This observatory just opens up this entire period of time for us to study," Rochester Institute of Technology researcher and CEERS investigator Rebecca Larson said in a statement. "We couldn't study galaxies like Maisie's before because we couldn't see them. Now, not only are we able to find them in our images, we're able to find out what they're made of and if they differ from the galaxies that we see close by."

The goal of investigations using the CEERS data will be to learn more about the formation of early galaxies.

"We're used to thinking of galaxies as smoothly growing," Finkelstein concluded. "But maybe these stars are forming like firecrackers. Are these galaxies forming more stars than expected? Are the stars they're making more massive than we expect? These data have given us the information to ask these questions. Now, we need more data to get those answers."