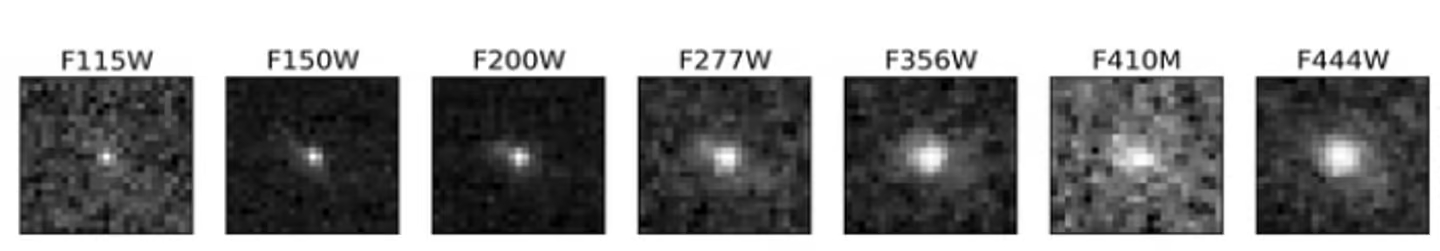

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have found what they say are three of our universe's earliest galaxies, spotted actively forming when the cosmos was just 400 million to 600 million years old.

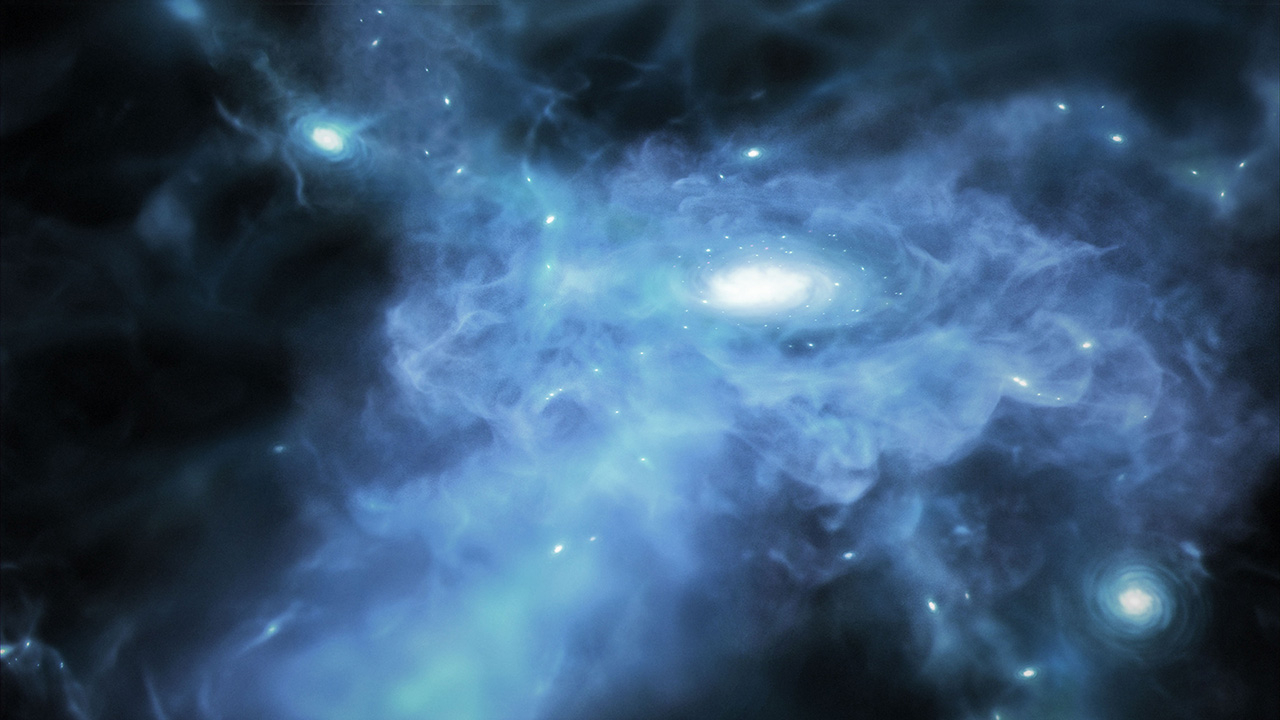

In the JWST's images, this galactic trio resembles fuzzy red smudges feeding on nearby helium and hydrogen.Over millions of years, it is these elements that sustain such galaxies as they grow, helping to shape them into the familiar ellipses and spirals we see across the cosmos.

"You could say that these are the first 'direct' images of galaxy formation that we've ever seen," study lead author Kasper Elm Heintz, who is an astrophysicist at the Cosmic Dawn Center (DAWN) in Denmark, said in a statement. "Whereas James Webb has previously shown us early galaxies at later stages of evolution, here we witness their very birth, and thus, the construction of the first star systems in the universe."

Related: Astronomers accidentally discover 'dark' primordial galaxy with no visible stars

About 400,000 years after the Big Bang, our universe was ushered into darkness. This occurred after space had cooled down enough from its formerly chaotic and scorching self to allow neutral hydrogen atoms to form, which blanketed the cosmos in an opaque primordial fog. That fog lifted about 1 billion years after the Big Bang, when light from the first generation of stars flooded the universe. Recent research has shown dwarf galaxies that formed during the first few hundred million years of the universe packed a surprisingly abundant punch to drive this fog-relieving process.

"This is the process that we see the beginning of in our observations," study co-author Darach Watson said in the university statement. "These galaxies are like sparkling islands in a sea of otherwise neutral, opaque gas," Heintz added in a NASA statement.

The legacy of a sparkling cosmic triplet

The JWST's powerful infrared eye was able to capture how light from the three observed galaxies was absorbed by large, dense reservoirs of neutral hydrogen gas around them — this result also showed that gas gathering into and feeding the galaxies themselves. There's so much gas in the scene, in fact, that the galaxies haven't yet birthed their first stars. In order for stars to be born, some sections of such primordial gas need to coalesce into extremely dense pockets, which then spurs the formation of stellar bodies. It would've likely taken millions of years for the first generation of stars to be born in these galaxies.

Astronomers don’t yet know how gas is distributed between the centers of galaxies, which also house supermassive black holes, as well as in galactic outskirts. Not only may future observations help solve that puzzle, but they could also reveal if these galaxies' gas reservoirs are entirely made of primordial hydrogen, or already sprinkled with heavier elements.

"It is a process that we'll investigate further, until hopefully, we are able to fit even more pieces of the puzzle together," said study co-author Gabriel Brammer of DAWN.

He noted that this discovery demonstrates the JWST is reaching beyond its primary mission goals. "Images and data of these distant galaxies were impossible to obtain before Webb," he said. "Plus, we had a good sense of what we were going to find when we first glimpsed the data – we were almost making discoveries by eye."

The findings are described in a paper published on May 23 in the journal Science.