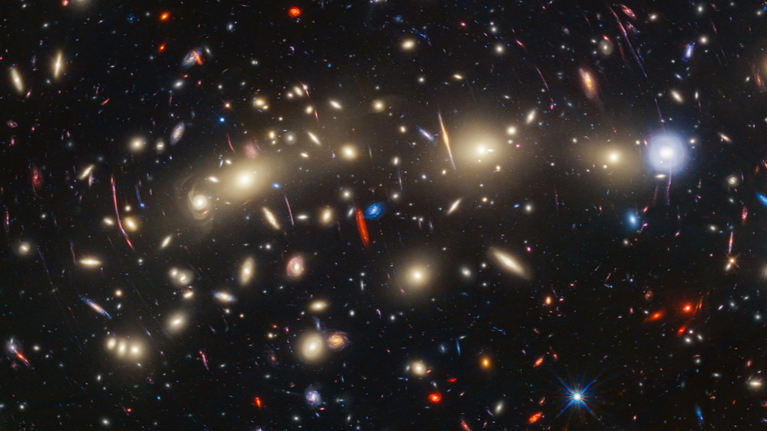

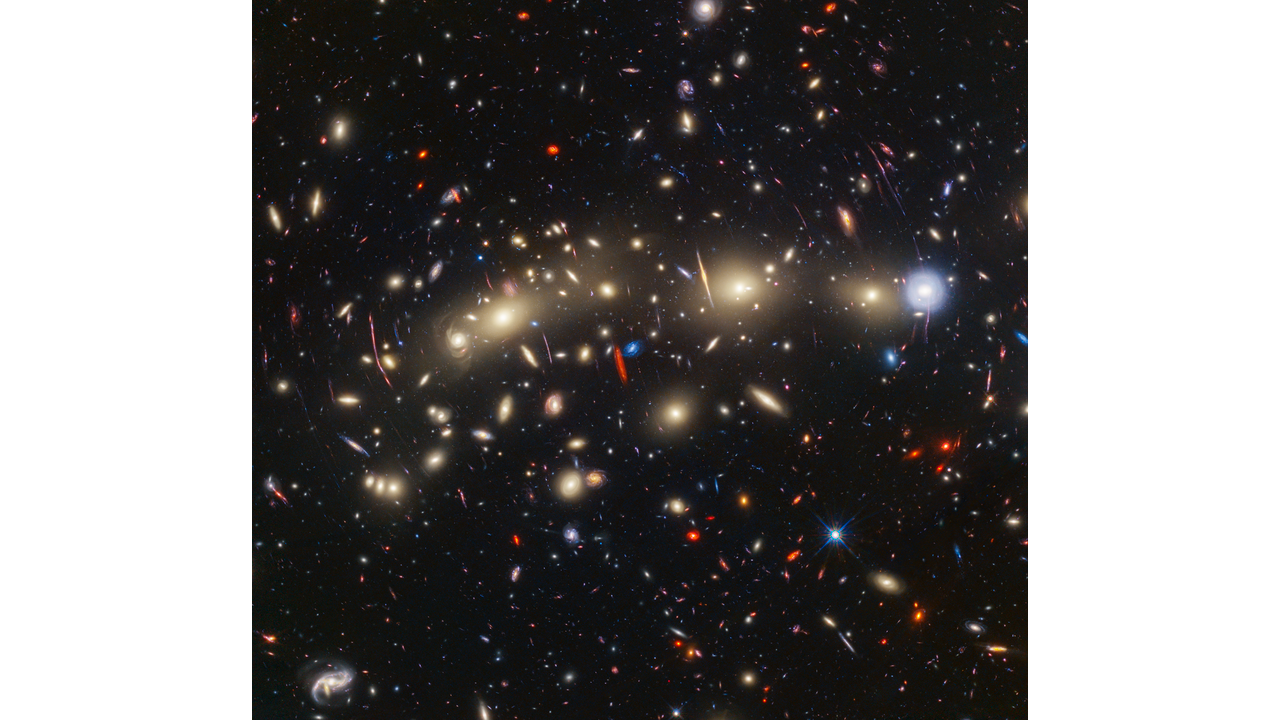

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) left astronomers feeling festive recently as it allowed them to image a distant, colorful cluster of galaxies they have dubbed the "Christmas Tree Galaxy Cluster."

In this cluster, the James Webb Space Telescope discovered flickering "Christmas lights" in the form of 14 new transient objects — celestial objects that brighten dramatically before dating . The winter wonderland is officially called MACS041, and is located about 4.3 billion light-years from Earth.

"We're calling MACS0416 the Christmas Tree Galaxy Cluster, both because it's so colorful and because of the flickering lights we find within it," Haojing Yan, an associate professor in the University of Missouri Department of Physics and Astronomy, said in a statement. "Transients are objects in space, like individual stars, that appear to suddenly brighten by orders of magnitudes and then fade away. These transient objects appear bright for only a short period of time and then are gone; it’s like we’re peering through a shifting magnifying glass."

Related: James Webb Space Telescope reveals most distant Milky Way galaxy doppelganger

Spotting so many transients in this galaxy was achieved by teaming the JWST up with the Hubble Space Telescope; the sheer number of transients spotted in one go, thanks to the duo, implies there are a lot more yet to be found within the Christmas Tree Galaxy Cluster. It's almost like the Christmas gift for astronomers that'll keep on giving.

Putting up the Christmas tree with Einstein

The light from the Christmas Tree Galaxy Cluster began its journey across the cosmos when the solar system, now 4.6 billion years old, was newly formed and just around 300 million years old. This would ordinarily make it too faint for even the JWST to see in detail, but a little trick first acknowledged by Albert Einstein made observing this cosmic Christmas a little easier.

In his 1915 theory of general relativity, which concerns the nature of gravity, Einstein said objects of great mass must warp the very fabric of space and time, united as a single entity called space-time, giving rise to a curvature we experience as gravity. And when anything — including light — passes these curved regions of space, those things' paths get curved. The closer to the body of mass a thing is, the more extreme the curvature it experiences.

As a result, when an object passes between Earth and a distant light source, the light from that background object takes a varied amount of time to reach us, as its path isn't following a straight line due to the curvature created by the passing object. This can ultimately cause that background object to appear amplified from our vantage point. The concept is called "gravitational lensing" as the intervening object acts as a natural, cosmic magnifying glass.

The JWST has been tapping into this phenomenon, with great success, to see some of the universe's earliest galaxies — and its view of the Christmas Tree Galaxy Cluster is its latest example.

"We can see so many transients in certain regions of this area because of a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing, which is magnifying galaxies behind this cluster," Yan said. "Right now, we have this rare chance that nature has given us to get a detailed view of individual stars that are located very far away. While we are currently only able to see the brightest ones, if we do this long enough — and frequently enough — we will be able to determine how many bright stars there are and how massive they are."

A monster in the Christmas tree?

The transients were found by Yan and the team as they were looking at four sets of images captured by the JWST over around four months, as part of the JWST’s PEARLS GTO 1176 program. The team has identified two objects in the images as supernova explosions that happen as stars reach the end of their lifespans. Yan is thrilled by this result, as he and his team can now use those supernovas to study the galaxies in which they are happening.

"The two supernovas and the other twelve extremely magnified stars are of different nature, but they are all important," Yan explained. "We have traced the change in brightness over time through their light curves, and by examining in detail how the light changes over time, we’ll eventually be able to know what kind of stars they are."

The astronomers also found something else extraordinary in the Christmas Tree Galaxy Cluster: A monster star in a galaxy, seen as it was when the universe was just 3 billion years old. They have named the star "Mothra" after the monstrous moth, Kaiju, from Japanese cinema.

The galaxy in which Mothra lurks was lensed to around 4,000 times its original brightness. The object lensing this galaxy is currently unknown, but Yan and the team estimate it has a mass of between 10,000 and 1 million times that of the sun. "The most likely explanation is a globular star cluster that’s too faint for the JWST to see directly," Jose Diego, research lead author and a scientist at the Instituto de Física de Cantabria scientist, said in a separate statement. "But we don’t know the true nature of this additional lens yet."

What is extra interesting about Mothra's galaxy is the fact it was also visible and lensed in Hubble Space Telescope images taken nine years ago. Normally, a lensing object and a background galaxy would move out of alignment over such a period, but Mothra's home galaxy and the object lensing it seem to have stuck together. In the future, Yan and the team hope to both figure out the nature of this lensing object and uncover some of its characteristics.

"We'll be able to understand the detailed structure of the magnifying glass and how it relates to dark matter distribution," Yan concluded. "This is a completely new view of the universe that’s been opened by JWST."

One of two papers detailing the observation of the Christmas Tree Galaxy Cluster was published in November in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, while the other has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal with a preprint available on the research repository arXiv.