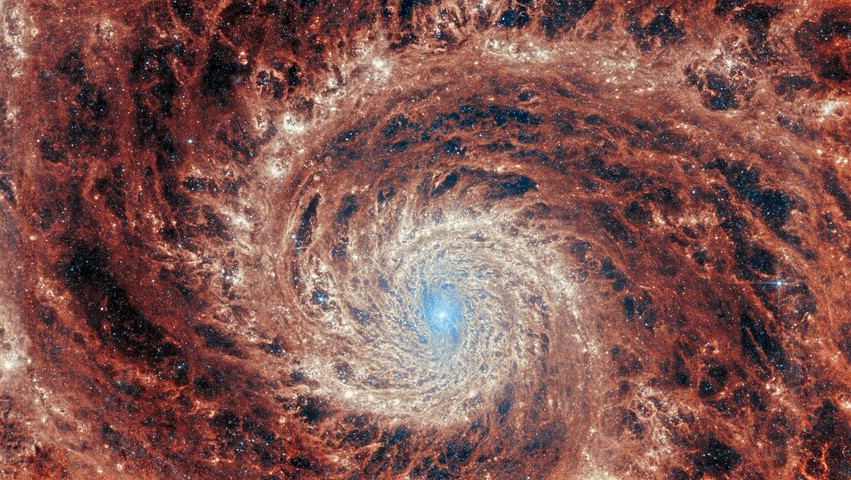

With a hypnotic new image released on Tuesday (Aug. 29), the James Webb Space Telescope allows us to gaze within a spiral galaxy floating some 27 million light-years away from Earth.

It's a vibrant snapshot representing a realm named M51 (also known as NGC 5194 or the Whirlpool galaxy) that brilliantly captures the rocky relationship this galaxy has with its nearby neighbor, a dwarf galaxy named NGC 5195. It is, in fact, partially because of this galactic interaction that M51 may have such an ornate pattern in the first place.

"The gravitational influence of M51's smaller companion is thought to be partially responsible for the stately nature of the galaxy's prominent and distinct spiral arms," the European Space Agency said in a statement about the visual.

And on the note of those stunning spiral arms, one intriguing fact about M51 is its winding structure dubs it a "grand-design" galaxy rather than just a standard spiral galaxy.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope and Hubble will help NASA's Juno probe study Jupiter's volcanic moon Io

While a typical spiral galaxy exhibits vortexed arms like M51 as well, grand-design spirals constitute about one-tenth of all spiral galaxies and possess very strongly defined arms that stem from a clear core region. Naturally, this makes them quite beautiful to look at from our vantage point on Earth. (It's technically up for debate whether our Milky Way is a grand-design galaxy as well).

ESA even calls M51 one of the most "photogenic galaxies in amateur and professional astronomy." As you can see, it's been a cosmic inspiration for as far back as 2001.

So, what am I looking at here?

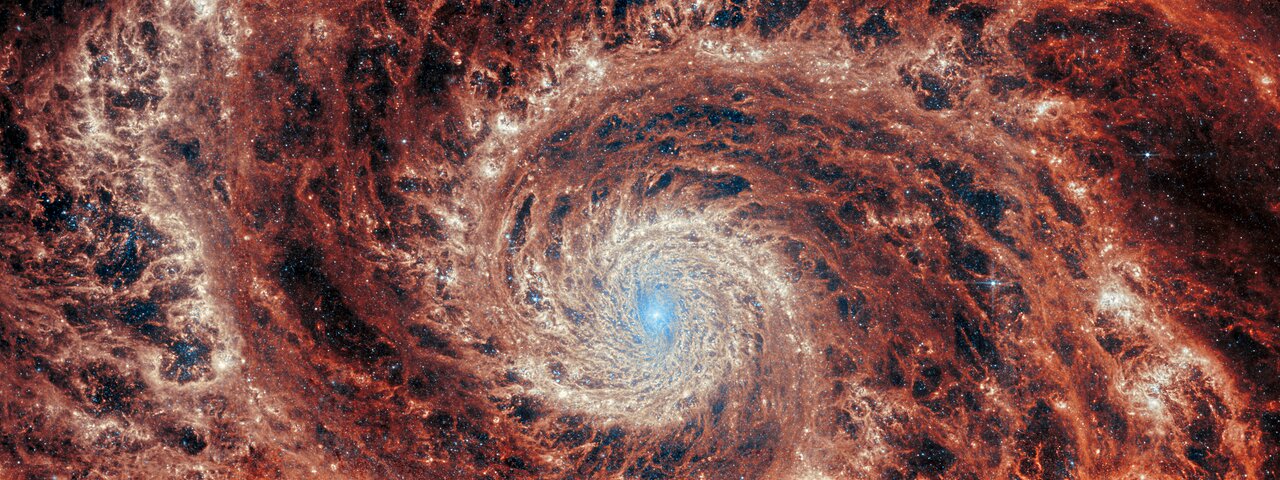

To image M51, the JWST tapped into two of its powerful infrared instruments: The Mid-Infrared Instrument and the Near-Infrared Camera. This, as you may expect, provided two separate perspectives on the galactic subject (though there is a composite image that combines the two).

Like their names suggest, both devices are built to capture the distant universe by decoding infrared light signals emanating from faraway stars and galaxies. Once such signals manage to make their way to the telescope's gold-plated, hexagonal mirrors, they're reflected onto the sensors which can then parse the data for us. This bit is actually why the JWST is considered to be such a big deal – human eyes cannot see infrared light (we can only see visible light) and so this machine is literally programmed to decode the invisible universe for us.

But what this means is, as with all JWST images, both M51 portraits have been colorized.

Yet the reason scientists infused such coffee-colored hues and allowed for shimmering white accents in these images of M51 goes far beyond aesthetics. Scientific artistry like this helps bring out some important details that may otherwise go unnoticed, blurred into the rest of the scene.

For instance, the dark red features in the NIRCam image, according to ESA, indicate warm filamentary dust in the realm while oranges and yellows show spots of ionized gas that were spurred by recently formed star clusters. "Stellar feedback has a dramatic effect on the medium of the galaxy and creates complex networks of bright knots as well as cavernous black bubbles," the agency explained.

Stellar feedback refers to the way stars pour energy into their surroundings, resulting in various processes that can dictate things like the rate of formation for other budding stars.

In the MIRI-centric image of M51, by contrast, empty cavities and bright filaments appear to alternate, presenting the impression of ripples propagating from the spiral arms. It also indicates a much more dramatic filamentary structure in general when compared to the NIRCam image. This is because certain light fragments associated with dust grains and molecules, the agency says, "illuminate the cold gas of the galaxy." Perhaps a welcome reminder that, despite some minor glitches the JWST team has reported with regard to MIRI, the instrument remains in good health.

And putting both the MIRI and NIRCam images together, scientists developed a composite photo that overlays all of those remarkable nuances.

Part of a series of observations known as Feedback in Emerging Extragalactic Star Clusters, or FEAST, these observations "were designed to shed light on the interplay between stellar feedback and star formation in environments outside our own galaxy," the agency said.

It was 2011 when a Hubble Space Telescope view of M51, taken in the visible light we can see, enticed scientists with its grandeur. Almost poetically, the team behind that whirlpool portrait stated that "although Hubble is providing incisive views of the internal structure of galaxies such as M51, the planned James Webb Space Telescope is expected to produce even crisper images."

Well, here we are.