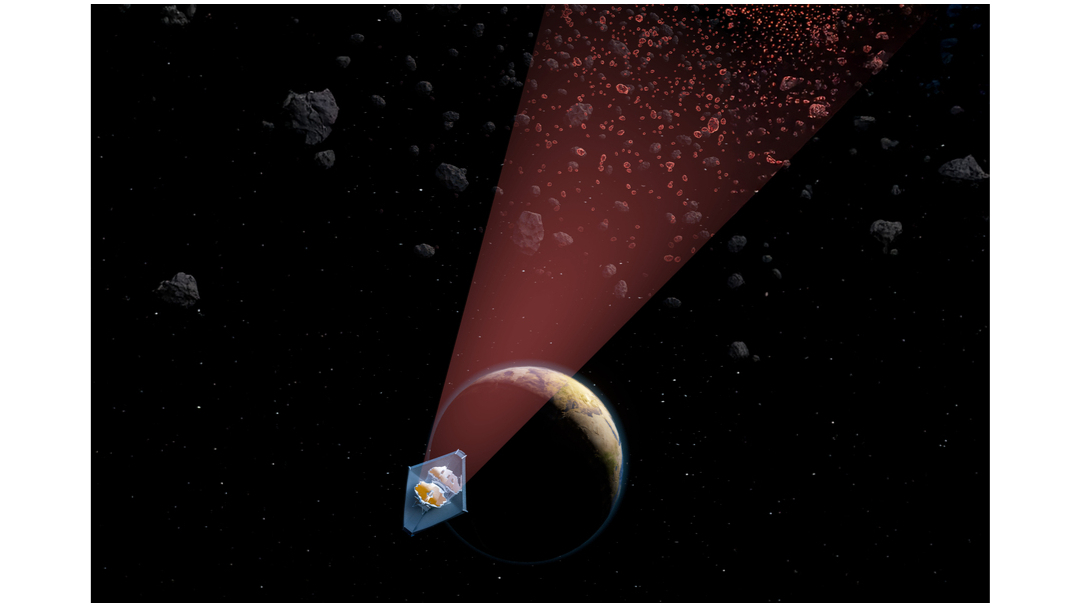

By reverse-engineering James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) exoplanet data, a team of astronomers just spotted dozens of tiny asteroids — including the smallest ever seen in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter.

The asteroids that are mostly likely to hit Earth aren't huge planet-killers, but smaller chunks of rock tens of meters wide — just big enough to wreak havoc on a city or a region. There are many more of these small asteroids, and they're more likely than their larger brethren to get nudged out of the main asteroid belt and migrate inward toward Earth. And because they're so small and hard to spot, astronomers might not see the next Chelyabinsk or Tunguska object coming until it's right on top of us.

"We have been able to detect near-Earth asteroids down to 10 meters in size when they are really close to Earth," Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) planetary scientist Artem Burdanov, lead author of a new study announcing the JWST results, said in a statement on Monday (Dec. 9).

But out in the asteroid belt, 112 million miles (180 million kilometers) away, where most of these small asteroids begin their journey toward Earth, the smallest object astronomers have been able to spot and track is about a kilometer wide.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) — A complete guide

Until now. Burdanov and his colleagues broke that record by finding a 33-foot-wide (10 m) asteroid hidden in JWST data, which was originally intended to search for atmospheres around the rocky exoplanets orbiting the nearby red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1.

"We now have a way of spotting these small asteroids when they are much farther away, so we can do more precise orbital tracking, which is key for planetary defense," said Burdanov. He and his colleagues published the work Monday in the journal Nature.

One astronomer's noise is another astronomer's treasure

If you're trying to capture an image of a planet passing in front of its star 41 light-years away, you need to filter out a lot of "noise" — things like asteroids, dust clouds and clumps of interstellar gas drifting through all the space between JWST and TRAPPIST-1.

One way of accomplishing that is to take multiple images of the same patch of sky, then stack them. The idea is that a faint but distant object, like the red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1, should stay in the same place, while closer objects like asteroids should move across the field of view.

When you stack several images of the same area, the result is several images of the star sitting on top of each other, making it look brighter. Meanwhile, all the faint, moving objects in the foreground, which only appear in one layer before moving on to another spot, look much fainter by comparison.

"For most astronomers, asteroids are sort of seen as the vermin of the sky, in the sense that they just cross your field of view and affect your data," study co-author Julien de Wit, also an MIT planetary scientist, and a member of the team that discovered the TRAPPIST-1 planets, said in the same statement.

But what counts as noise and what counts as data depends on what you're looking for — and this time, Burdanov and his colleagues wanted to look for small asteroids, which show up as faint, constantly moving pinpricks of infrared light in the JWST data. The team worked their way through 10,000 images of the TRAPPIST-1 system, looking for faint smudges of light in the foreground that could be main-belt asteroids.

Every time the astronomers thought they'd found an asteroid, they had to look at even more images of the surrounding patches of sky, to test their estimates about where the asteroid's orbit might have taken it next. In the end, they tracked down 138 previously undiscovered small asteroids, ranging from 10 meters to a few hundred meters wide.

"We thought we would just detect a few new objects, but we detected so many more than expected, especially small ones,” de Wit said. "It is a sign that we are probing a new population regime, where many more small objects are formed through cascades of collisions that are very efficient at breaking down asteroids below roughly 100 meters."

"This is a totally new, unexplored space we are entering, thanks to modern technologies,” Burdanov added. "It’s a good example of what we can do as a field when we look at the data differently. Sometimes there’s a big payoff, and this is one of them."