When the James Webb Space Telescope revealed its first five images to the public in July, the scientific community was amazed. The ambitious project had involved decades of work, and it had paid off with some of the most detailed images of the distant universe ever put together.

Foremost among these achievements is how the telescope has allowed humans to better observe and catalog exoplanets, or planets that exist outside of our solar system. NASA describes the telescope as tailor-made to study those elusive bodies — which, by virtue of their comparatively smaller size, are far harder to image than distant stars. Webb is particularly adept at observing the atmospheres of exoplanets — an exciting endeavor, as understanding their chemical composition could be the key to scientists discovering extraterrestrial life.

The thrum of news items about Webb's findings is almost nonstop, which is why we put together this list of all the planets that Webb has observed so far. For some of these, Webb has merely observed the composition of their atmospheres; another historic image features the first ever direct image of an alien world. In addition, a recent image of Jupiter has helped redefine how we understand the largest neighbor in our own solar system.

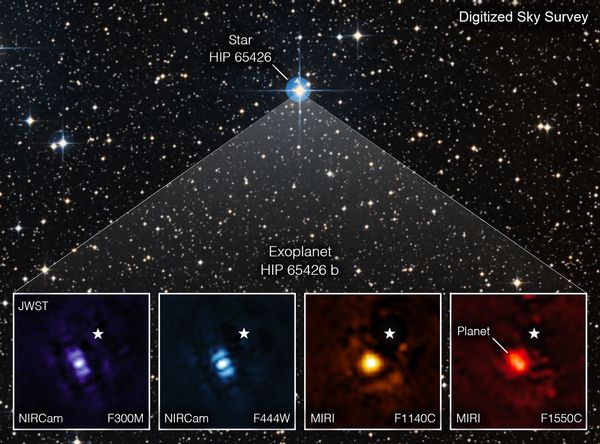

This historic exoplanet marks the first time that the James Webb Telescope has ever taken a direct picture of an exoplanet. (It's not quite the first exoplanet image ever, though: Hubble took the first, in 2008, after eight years of work.) Indeed, though grainy, these images are a reminder that telescope images are artistic renderings just as much as they are "objective" scientific depictions. There are different cameras on the telescope, each of them operating in different wavelengths and with different filters, and as a result the images of the exoplanet HIP 65426 b and its surrounding area range from bright blue and deep purple to fiery red and a tiny yellow dot. Each one uses a coronagraph to block out the light from the planet's own sun, and then the exoplanet HIP 65426 b region is shown in varying bands of infrared light. No one image is the "correct" one; they are equally accurate, and equally beautiful, albeit from different points of view.

What we know about this distant world is this: it is a gas giant, estimated to be six to twelve times as massive as Jupiter. And it orbits its own star at about one hundred times as distant as Earth orbits the Sun.

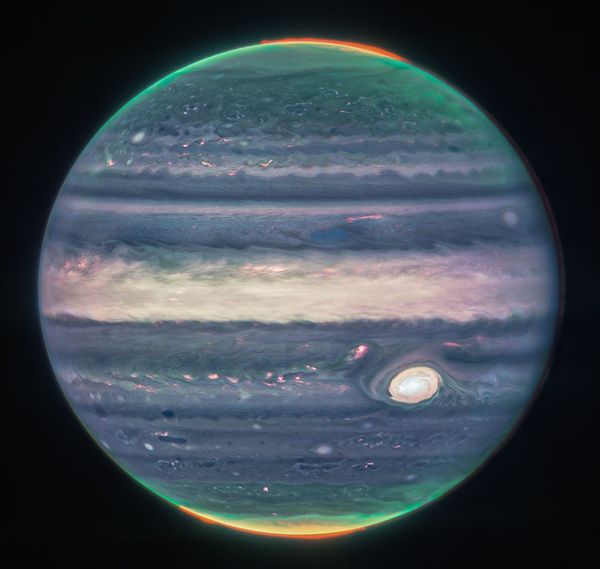

When you think of Jupiter, the fifth planet from our sun as well as the largest, the chances are you imagine it with orange, red, yellow and white swirling bands — as well as its iconic Great Red Spot south of its equator.

Yet as the James Webb Telescope reminds us, these images are as much interpretive as they are objective. In the case of Jupiter, the telescope has three specialized infrared filters that provided new data about Jupiter by measuring different wavelengths of light from the behemoth planet. With the help of a citizen scientist, Judy Schmidt, who translated that data into actual images, NASA scientists were able to compose a shockinly detailed view of Jupiter. You can see auroras, or beautiful light shows that appear in the sky, in Jupiter's atmosphere. There are crackling storms, sweeping winds and unimaginable heights and lows of temperature. The false-color scheme is wildly different from what a backyard astronomer might see if they were to stare up at Jupiter.

One of the benefits of the James Webb Telescope, and of space telescopes in general, is that they can observe in the infrared part of the spectrum. Because of interference from Earth's atmosphere, our ground-based telescopes cannot achieve this feat. Hence, these Jupiter photos are literally taken in a "new" light.

In the case of many of these exoplanets, the James Webb Space Telescope has observed an exoplanet's atmosphere, which is typically easier than imaging said worlds directly. In the above illustration, we get an idea of the appearance of an exoplanet called WASP-39b. A gas giant orbiting a Sun-like star 700 lightyears away from Earth, WASP-39b has carbon dioxide in its atmosphere, much like Earth or Mars. That last information came courtesy of the James Webb Space Telescope itself, and in the process WASP-39b became the first exoplanet to have confirmed carbon dioxide in its atmosphere. This finding will hopefully help scientists detect carbon dioxide on rockier planets with oceans, and where its presence could indicate life.

"As soon as the data appeared on my screen, the whopping carbon dioxide feature grabbed me," Zafar Rustamkulov, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University and member of the JWST Transiting Exoplanet Community Early Release Science team, told NASA in a statement. "It was a special moment, crossing an important threshold in exoplanet sciences."

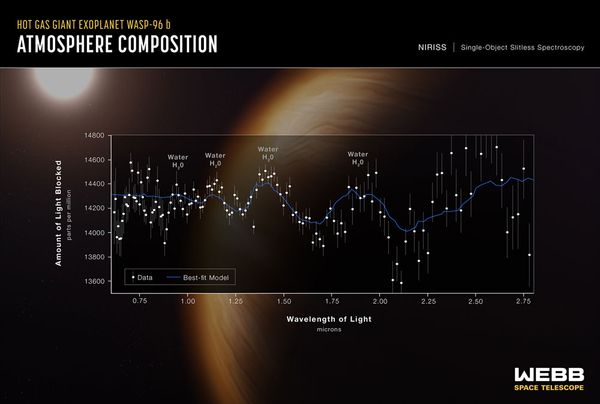

If you want to imagine a planet out of a bizarre science fiction tale, look no further than WASP 96-b. Because it revolves around its sun every 3.4 days (by contrast, we revolve around our Sun every 365.25 days), temperatures usually hover at around 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (538 degrees Celsius). Despite being a gas giant like Jupiter, WASP 96-b is only half of Jupiter's size — but is also described by scientists as much puffier in its appearance.

To measure its atmosphere, the scientists behind the James Webb Space Telescope used a device called the Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph, which provided the most detailed measures of any exoplanet's atmosphere ever recorded. Strikingly, the telescope discovered traces of water, clouds and haze in WASP 96-b's atmosphere, none of which were previously suspected to have been there.

The scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope are currently observing exoplanet 55 Cancri e, and are hoping to do with it what they did to WASP-96b. 55 Cancri e is also a strange world, with temperatures shooting up to 4,400 degrees Fahrenheit (roughly 2,400 degrees Celsius) because it is so close to its sun. It is a rocky planet twice as large as Earth — and its atmosphere remains a mystery to scientists. Previous studies have ruled out carbon dioxide, water and thick hydrogen in its atmosphere. Scientists hope to learn whether 55 Cancri e even has an atmosphere, and if so what is it made of. They also hope to determine if the planet is tidally locked to its Sun-like star; being tidally locked would mean that it is stuck in co-orbit with a different astronomical body, and in such a way that it loses any net change in its rotation rate during a complete orbit. That will help scientists figure out if 55 Cancri e's surface is permanently molten, which would be the case if it was tidally locked, or whether it experiences day-night cycles like parents which are not tidally locked.