Green co-leader and others pay tribute to Philip Mann

Reading Room literary editor Steve Braunias: Philip Mann died on September 1 in Wellington. He was 80. Born in Yorkshire, he established the first programme of drama studies at Victoria University in 1970, directed plays by such New Zealand writers as Greg McGee and Vincent O'Sullivan at Downstage Theatre, and was the author of 11 science fiction novels. His latest, Chevalier & Gawayn (Mann's synposis: "The world being in a bit of a mess, a hero from the past steps in to bring his own unique solutions") was launched shortly before his death. "I write from the heart," he once said. "Writing is extremely emotional, and not infrequently I have to stand up and walk away from the typewriter, computer, whatever, as the emotion is so great." In that same interview, he talked about how he only knew his mother, and that his father, "as far as I know, was a South African serving in the Merchant Navy…It was a disastrous marriage, and the only thing she took away from it when the wretched man deserted her, was a baby boy, me. I was, and remained, an only child. She became, and remained, a solo mother." As a sci-fi author, he was recognised internationally as a master of the form; the respected Australian journal Science Fiction: A Review of Speculative Literature devoted a special double-issue to his work, and his novel The Disestablishment of Paradise (2013) was shortlisted for the prestigious Arthur C. Clarke Award in 2013. The book was his own personal favourite: "It's concerned with the destruction of natural habitats on another planet, but at the same time is an examination of the problems we face now on Earth," he said. The book had a profound affect on James Shaw, who leads the tributes to Philip Mann, below.

James Shaw, co-leader of the Green Party: I read Phillip Mann’s novel The Disestablishment of Paradise shortly after returning home from many years overseas. It's one of those very rare books that still enters my thoughts.

It's a paean of deep environmentalism: a human colony on the planet Paradise is withdrawn in the face of increasingly hostile ecological forces. Mann gives literary being to James Lovelock’s and Lynn Margulis’ Gaia hypothesis that life on Earth isn’t just the sum of its parts, but that all living things are interconnected into an extraordinarily complex ecological system.

As good science fiction does, Paradise confronts us with painful questions about ourselves. The largely unspoilt fictional planet contrasts sharply with our current despoliation of the Earth, without mentioning it once.

Coincidentally, at about the same time, I read Peter F. Hamilton’s Great North Road, which contains similar themes of seemingly self-aware planetary ecologies responding to human incursion. But Great North Road doesn’t stick in my thoughts nearly as much as The Disestablishment of Paradise, which was shortlisted for the Arthur C Clarke Award for science fiction.

I was very saddened to hear that Mann had recently passed away. His book will continue to gnaw at me for years to come.

Whiti Hereaka, author of Kurangaituku: Phil worked with me on my second draft of my first novel, The Graphologist’s Apprentice. I remember my sister telling me that he was famous as a novelist overseas, but not really recognised here. I remember the thrill of finding a copy of The Eye of the Queen in a second-hand bookstore.

I remember following him down the stairs to his office space under his home. The walls were book lined ceiling to floor and there was a table for us to work on.

And then Phil would ask me questions about my novel — could my character really break into a house through the cat door the way I described it? (Yes, that’s how I’d break into my house as a teenager); did I intend my character to skirt that closely to madness? (Hmm, no — maybe I should rewrite that bit) and probably the most important question that I still ask myself today: does this serve the story, or just your ego?

Phil taught me so much about writing and teaching — and I often think of our exchanges in his office when I’m asking the same questions of new writers.

Ka aroha to his family, he will be greatly missed.

Quentin Wilson, publisher of Mann's latest novel: I first read his science fiction in the late 1980s when I discovered his evocation of alien culture, The Eye of the Queen. And then, in 1996, I had the pleasure of publishing a collection of short stories, Tales from the Out Of Time Cafe, with Phillip as title editor and which included two of his own stories.

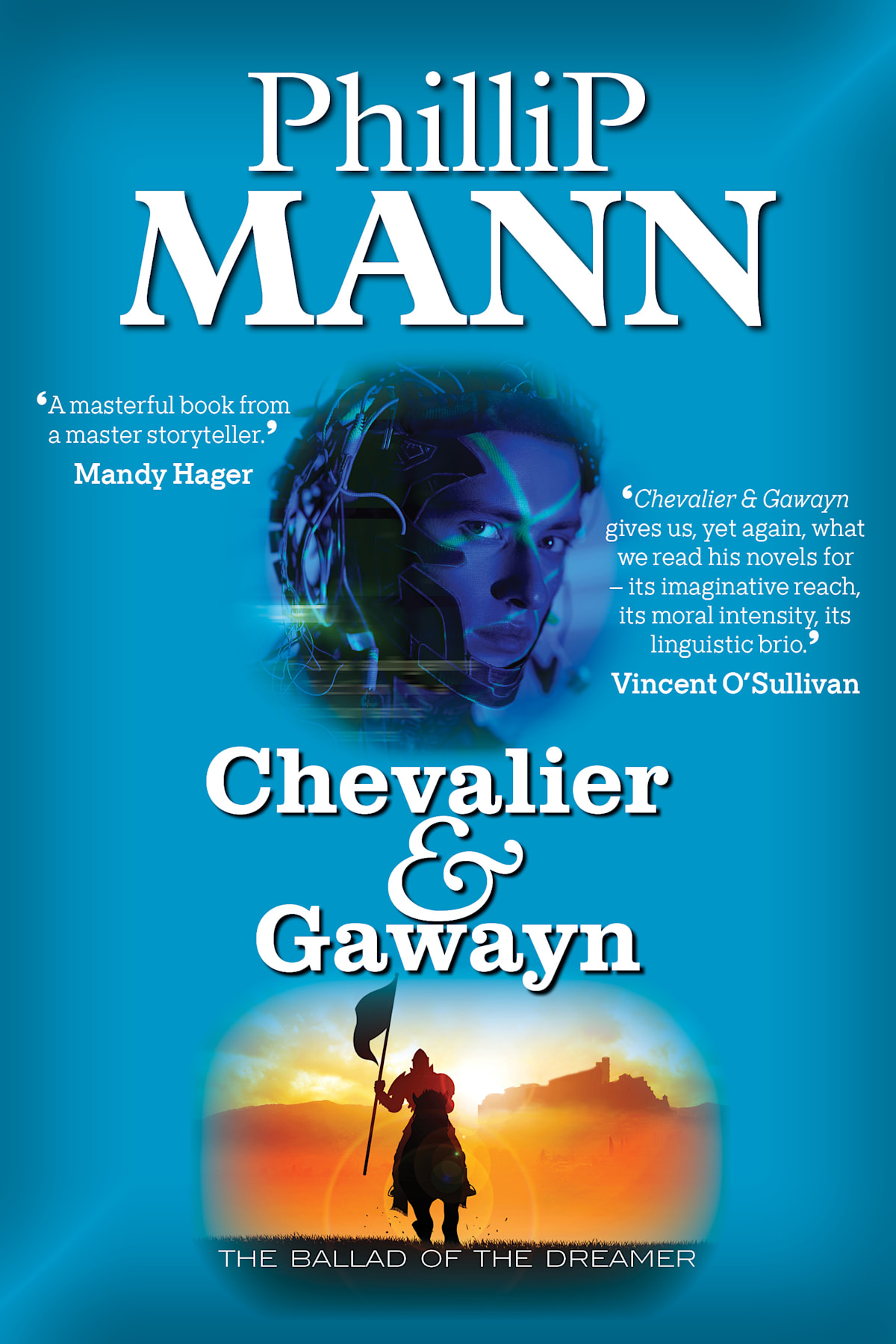

I am the proud publisher of his last novel, Chevalier & Gawayn: The Ballad of the Dreamer, a novel so prescient for our times and immediate future that I could add soothsayer to Phillip’s many talents. He created two complete and believable worlds where past and present spoke to each other through his rich panoply of characters, and nothing less than the future of humankind and the world took centre stage.

Chevalier & Gawayn was first presented as two novels – Books 1 and 2 – but we agreed to rework the two into one complete masterpiece. What a pleasure it was to do this with an author who appreciated the many cuts, merging and reworking the editing process demanded. Few other authors would take the direction, "Let’s leave them there for now – the horse can look after himself and we need to get back to the palace" with such calm good humour.

Mandy Hager, former tutor at Whitireia: What I most especially love about Phil’s writing is his amazing ability to make it feel both mythic and deeply personal at the same time, marrying head and heart, taking you to new worlds so ingeniously and beautifully imagined that they feel real, as if you’ve already visited them in dreams — while understanding the human psyche so well, with all its gifts and frailties, that the characters live on in your head long after you’ve finished.

I’d also like to acknowledge the incredible gift Phil gave to so many other writers over the years as a mentor. In my decade tutoring at Whitireia, I saw Phil time and time again teasing out each writer’s nascent talent, supporting them, stretching them, guiding them to the real core of the story, teaching them how to use their own emotional experiences to feed their fiction and give it heart.

Renée, playwright of Pass It On: Philip Mann directed my play Pass It On for the April 1986 Downstage production. Before rehearsals started, we met to talk about the script, about my ideas, his ideas. He was cautious about expressing his ideas, I was cautious too – it was a relief to find he not only knew about the 1951 Waterfront Lockout, which is central to the play, but had also read and thought about the characters, their various stories and settings, the lines. He had questions I could answer, production suggestions I could think about. I could relax.

Vincent O'Sullivan, playwright of Shuriken: In the late 1970s, before I returned to Wellington, the best reason for visiting there was getting to know Philip Mann better. From our first meeting I liked him, and liking quickly enough meant admiring him, deeply. I was taken with his gritty Yorkshire directness, and that it seemed not to occur to him quite how much he had to offer the city he came to. From the start, you were struck by his warmth, and his almost disconcerting gift for focusing so completely on what mattered to him.

I had seen quite a lot of theatre in the UK, and here at home, but I’m afraid that as a teacher, a play in a classroom meant pages to be read. Phil quickly strafed the error of that. A play was always theatre. It truly existed only in performance, its characters were actors, it moved in real time. In my years at Victoria, and for many before that, as I walked to the Drama studio in Fairlie Terrace, I was exhilarated before I arrived. The chances are I would find Phil and his drama colleagues knee-deep in the demanding practicalities of raising a play from page to stage. You could see and hear the text stirring into life, as students shared the practical physical skills of being on stage, slap-bang into the intricacies of its speech, learning the craft of its structure and pace.

What Phil so offered others was the passion of his teaching, his certainty that theatre was central to what life as a community might mean. Hundreds of students caught the fire of his certainties. He drew thousands of Wellingtonians, through his productions at Downstage and other venues, to a fresh awareness of fine contemporary drama, to experiencing why his hero Brecht was the breaker and maker of modern theatre, to feel the compelling force the classics still carried, and to share his belief in an emerging local voice. And theatre, for Phil, was always political, in that broad sense of showing us how lives are lived, and what forces compel or drive them. There was nothing that interests us, that theatre could not amplify.

What I so loved Phil for, as a friend and a mentor, came down to something quite simple. He engaged with people directly, assuming they had the same sincerity as he himself. I’ve not so much as mentioned that other impressive side of his deepest interests – the imaginative reach and constant moral alertness of his science fiction, and the international respect it was held in.

Nor so much as hinted at what diverting company he could be, his gift for bread making and for binding lovely manuscript books as gifts, his enthusiasm for folklore and water-divining and crop circles, his interest in mythologies and Asian theatre. His rare abilities as a builder, the years in France in his retirement, the importance of his family. So much crammed into the life of a good man.

The new science-fiction novel Chevalier & Gawayn: The Ballad of the Dreamer by Philip Mann (Quentin Wilson Publishing, $37) is available in bookstores nationwide.