On graduation day, outside the Barry Switzer Center, the air is heavy, thick, sticky, presaging the thunderstorm threatening to erupt. Traffic snakes through the streets lining the Oklahoma campus. Sweat spots polka-dot dress shirts. True love becomes sharing ever-dampening handkerchiefs with ever-more-desperate relatives.

It’s early afternoon when an NFL quarterback who’s better known for the other college he attended strolls into the training facility named after a famous Sooners coach. This is Oklahoma, so of course the athlete ceremony takes place atop an indoor turf field adjacent to the weight room. The forecast forced the university-wide graduation, the evening portion of this festive spring Friday, indoors.

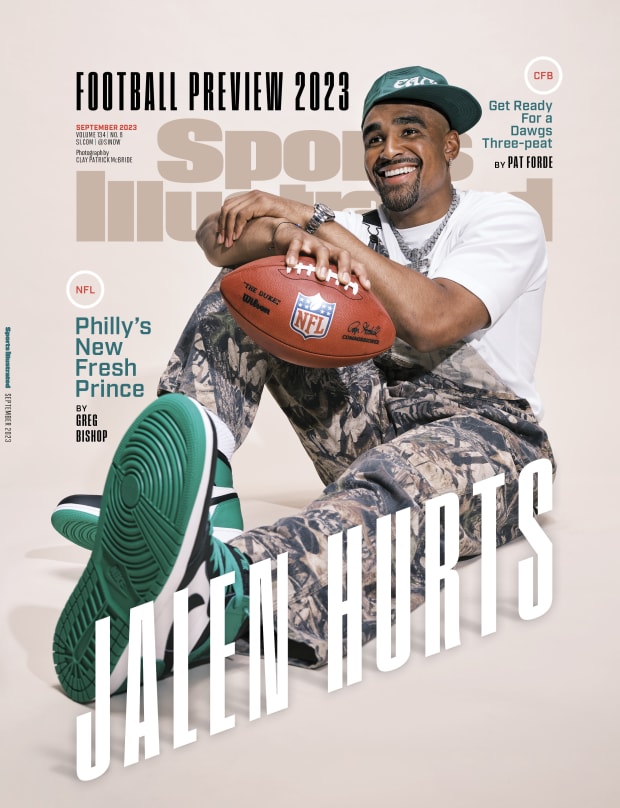

Beyond the hash marks, the field is outfitted like any other graduation (balloons, white folding chairs, champagne flutes). But on this day, in this place, for this quarterback, it’s also typical but in a different way. For Jalen Hurts, this day in mid-May opens a window into his superpower: intention. While not a novel concept in sports, Hurts’s application of purpose, the thorough, deliberate, precise and varied ways he deploys intent, stretches far beyond what’s typical.

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

Few superstars decide to finish their educational pursuits while acclimating to the NFL. Fewer still are quarterbacks on the cusp of careers that now project far beyond the wildest of pre-draft expectations. Even fewer obtain master’s degrees, as Hurts did. Fewer still return to a stopover where they spent just one season. But Hurts is here. Of course he’s here, because in his hand he holds a cellphone, and on that cellphone is an itinerary—every meeting, break, speech, meal and ceremony, scheduled to the minute.

This says a lot about Jalen Hurts, as does the story longtime athletic director Joe Castiglione tells the crowd. The first time I met this young man . . . He’s off! Oklahoma was the fourth program Hurts visited (Miami, Maryland, Ohio State) after completing his undergraduate degree (public relations) at Alabama, after the infamous benching and the backup season. The transfer tour highlighted jarring contrasts in cities and campuses. Hurts wanted it that way. But after only one day in Norman, he knew where he would play.

Hurts needed another degree about as much as he needed another throwing arm. He could have shown up, enrolled in easy classes, played a season with an eye on the NFL draft and departed with roughly the same life he has now. But, Hurts explained to Castiglione, that wasn’t his plan. When Hurts’s own brother calls him The Robot, this is why: the designs/itineraries/ resolute core. Hurts would not consider agents before or during the season. He would narrow his focuses to football and an advanced degree in human relations, which he planned to apply initially to leading football teams. Like the Eagles.

“What are the chances?” Castiglione asks the crowd.

For most, low. For Hurts, 100%. He approached that 2019 season like he does everything else, by thinking through every decision, speech, interaction, practice, game, class and test. He considered every sentence he uttered and many he never said. Same as always and same as now, when Castiglione beckons him onstage. Beyond a rare joke—about the dozen-plus silver trophies lined up like gleaming bodyguards; “quite the flex,” he calls it—Hurts delivers a short, direct, efficient speech that he clearly had rehearsed and memorized.

A parade of Sooners athletes swarms him afterward, asking for selfies, group pics, even autographs. One yells out, “Go Eagles!” Like all of them, Hurts receives an oversize ring for the degree completed. He proudly throws his on (left hand, index finger), but that’s not the ring he wants. He’d trade a thousand of those rings for the one he almost seized last February.

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

J, how are you feeling?” asks his agent, Nicole Lynn. Both stroll from the turf party to the next stop on the firmest, most detailed itinerary in graduation history.

Much has changed over the previous 12 months. A lot. Everything. More than expected. Not nearly enough. Graduation day is proof. Hurts doesn’t waste an hour, let alone a day. So when he later says, “There’s so much more of my story to be told,” the significance of his year at Oklahoma becomes clear. It’s the pivot from Alabama to now.

Hurts moves with intent. Eats with intent. Reads, watches and consumes with intent. Last February after Super Bowl LVII, Hurts stood before his Philly teammates inside their locker room. He had thrown for 304 yards and scored four touchdowns but insisted they blame him for their loss to the Chiefs. What??? Hurts made one obvious, critical mistake: a second-quarter fumble that K.C. linebacker Nick Bolton scooped up and returned for a score. The truth missing from Hurts’s message didn’t matter. Intention did.

He didn’t lose the Eagles anything. But he did convey accountability, status, leadership—gains. And that application of the concept that defines him showed that he’s not always robotic, that he might memorize speeches and shape itineraries but he also can adapt, reading rooms to formulate plans in real time.

That night, an Eagles staffer approached. “Bro, you’re a big reason we got here, and you’re a big reason we’re gonna get back, and we’re gonna finish this thing.”

Hurts made direct eye contact, pupils ablaze, posture impossibly upright. He needed only three words to define the Eagles’ upcoming season. “You’re f---ing right.”

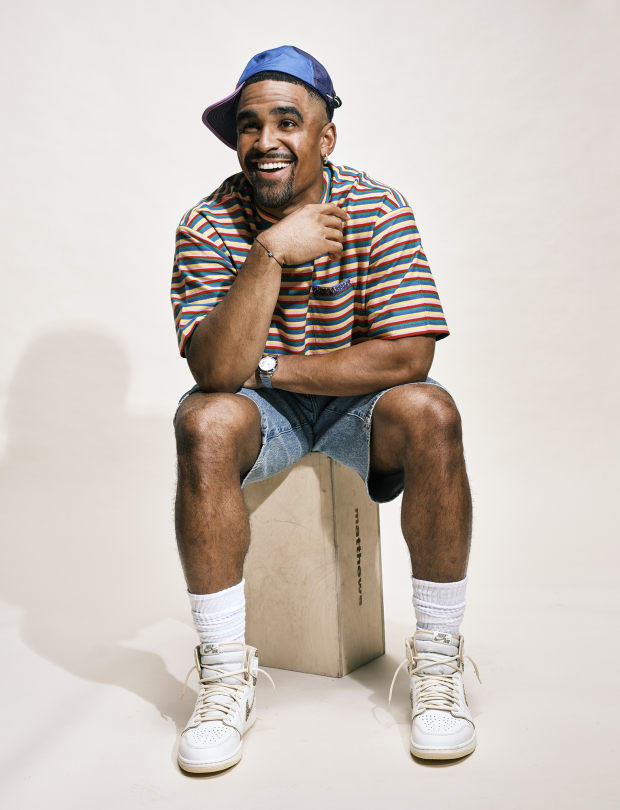

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Graduation day unspools with two powerful female influences by Hurts’s side. He has a lot of those. One is his girlfriend, Bry Burrows, who met Hurts at Alabama. The other: Nicole Lynn, an Oklahoma alum turned lawyer-agent–power broker, the president of football at Klutch Sports Group. All climb the stairs toward the Sooners coaches’ offices, stopping to pause at the rich history (Sports Illustrated covers, trophies, framed jerseys) hanging from the walls.

Lynn never expected to represent Hurts, let alone for him to respond to a you-don’t-know-me-but Instagram message she Hail Mary’d his way before the 2020 NFL draft. She hit send inside a Florida hotel room, while at a bowl game hoping to sign another prospect but too sick to climb out of bed. Hurts did respond, that day, his message purposeful, direct. “Call my dad.”

Perfect, she thought. Lynn lived in Houston, same as Averion Hurts Sr., the longtime football coach at suburban Channelview High. She flew back, sick as hell but undeterred. The elder Hurts reversed roles, putting the agent-lawyer through a cross-examination that lasted nearly four hours. She coughed and wheezed and tried not to throw up. Of course, she later discovered that Jalen designed much of the interview himself. She realized then what would become achingly clear: “There’s nothing surface level about him.”

The sides reached an agreement. The partnership worked well. Still, last spring was a critical stretch. Lynn continued building her client roster, with Hurts as an enticing centerpiece, while negotiating with the Eagles for the extension his play forced. The potential for the deal, which was at best a possibility a year earlier, ballooned. During Philadelphia’s playoff run, Lynn jokingly crowdsourced social media to see whether anyone knew where to find a Brink’s truck.

Hurts chose to minimize his role in negotiations, providing Lynn with detailed, Hurts-ian instructions. During his conversation with Eagles GM Howie Roseman after the season, Hurts stuck to football topics. The extension came up only when Roseman noted its perch atop his offseason priority list. “O.K., sounds great,” Hurts responded. He wanted to be “paid what I’m worth,” he told Lynn, but not so much as to hobble Roseman’s ability to build a championship- caliber roster around him. In the months that followed, Hurts never asked his agent or GM for an update. Lynn provided only one, when the agreement was imminent.

Instead, the build continued. After setting career highs in completions, accuracy, passing yards, touchdowns and most advanced metrics, and finishing second in MVP voting, he wanted but one thing—more. He doubled workout sessions, visited coaches in California and continued to rehab a December shoulder injury.

Hurts no doubt saw Roseman completing an elite offseason of his own (coaxing back veteran cornerstones, re-signing starters, bolstering depth, snagging impact players in the draft). Hurts did not ask to give input, electing, in this instance, for intention through inaction. Instead, he drops the word sovereignty in reference to the GM and his job.

Hurts retains sovereignty over only himself, and he rules his world with unflinching self-control. There’s always a point. This spring, he studied two of his greatest athlete influences: Michael Jordan and the late Kobe Bryant. He examined how Bryant evolved, especially when confronting injuries or other adversity. How Bryant’s leadership grew and changed stood out to him. With Jordan, Hurts wanted to understand how the most elite athlete handled the heightening attention at the top stratosphere of sports success. Jordan, he learned, tightened his circle, protected his time.

In mid-April, Lynn called with that update. The parameters were stunning—five years, up to $255 million, $179 million guaranteed and $110 million of that coming the second Hurts signed. The average annual salary—$51 million—marked the highest in NFL history (since surpassed by Lamar Jackson). Hurts agreed in principle while in Los Angeles, which sounds flashy but wasn’t at all. The Robot was there to train. He went right back to workouts, film study, gratitude lists. He visited his coach at Oklahoma, Lincoln Riley, now at USC, to share and solicit impressions.

He came away with another intention: “Money is nice. But championships are better.”

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

Most members of this OU graduating class were born after 2000. But not the quarterback in attendance. While Hurts, 25, spent only 16 months in the previous decade, his ethos is as ’90s as Nirvana.

Start with his mother, Pamela, an educator who tuned the radio to R&B stations and the TV to The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. “I enjoy those vibes,” Hurts says, before describing his soul as old school. Vintage also works. Or vinyl. He partnered recently with the Jordan Brand, an impact powerhouse that shaped that decade.

Sometimes Lynn wonders whether Hurts is 25 or 45. “I’m like, ‘Chill out. Can you relax?’ ” she says. “But that’s definitely who he is.” His parents asked the same questions. Their middle child clung not to stuffed animals but fixed routines. Every weekday afternoon after middle school, he took a nap at the same time. Every Tuesday, he ate Popeyes; every Friday night, he was the most serious ball boy in Channelview football history. Every time his older brother, Averion Jr., went outside to shoot hoops, Jalen followed. “Always been a robot,” Junior says. “Always very habitual.”

When Jalen practiced football he’d do it by himself, catching passes he lobbed high in the air or juking trees in the yard with spins and stiff-arms. Dad, who directed the gridiron upbringing, held Jalen out of organized football at first. Senior sensed something distinct inside the boy who carried a ball everywhere he went. He wanted Jalen to hold on to the purity of his pursuit as long as possible. Jalen dived into baseball instead; first as an ace pitcher and later as a shortstop who projected as a potential MLB outfield prospect. He was naturally right-handed but swung the bat lefty, foreshadowing the coordination and athleticism he would deploy on football fields. Senior relented, in part, for practical reasons. Bringing his boys to practice doubled as free childcare. He didn’t mind if they hopped into drills or listened to meetings, so long as they followed two rules—shut up and don’t break anything. It was Jalen, the younger brother, who set up in Pops’s office, forever silent and stoic. “I never thought he was paying attention,” Senior says.

Courtesy of the Hurts family

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

After stints as an offensive lineman, pass rusher and tight end—Dad’s review: terrible—Hurts became an accidental quarterback, switching positions out of necessity. He had been listening, absorbing, all along. At Channelview he mastered an offense that combined the spread’s soul with Air Raid tendencies. The Hurts family ended the school’s 22-year playoff drought, together, as Jalen, the old soul, morphed into a replica of his dad. “They really are the same person,” Junior says. “Jalen really tried to be just like him. I’m like, ‘No, you gotta chill out, dude.’ ”

While his on-field bearing came from Dad, Jalen’s personality and approach to off-field endeavors came from Mom. But it wasn’t until last season that his ’90s soul and career collided in the best possible way. After a home win over Dallas, a Fresh Prince superfan (Eagles coach Nick Sirianni) and an Eagles superfan (DJ Jazzy Jeff of Fresh Prince/music fame) bumped into each other in the locker room. Jeff even did his signature Fresh Prince handshake.

“Call me Jeff,” the deejay says over the phone, while explaining that he normally doesn’t do this greeting for anyone other than his costar from the show, Will Smith. The first time that Jeff transferred the dap-up was with Sirianni. The second instance came before the NFC championship game, when Jeff and Hurts bumped into each other on the field. They slapped palms, shook arms and snapped fingers while looking in opposite directions. Just like on the show. The moment went viral. The Robot became human. “So cool,” he says.

Point is, Jeff saw Hurts’s mother’s influence, his father’s influence and how the quarterback combined both into his authentic self. Jeff believes that’s why a fan base of infamous boo birds has embraced its latest star. Because they see something like the best version of themselves. “He doesn’t get too high; he doesn’t get too low,” says the deejay. “And people really appreciate that he came in and did the work.” Now Hurts has unlimited handshake access.

Anything, Jeff says, for Philly’s new Fresh Prince.

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

On graduation day, Hurts and Burrows sink into the red leather couch in Brent Venables’s office. The space resembles a chapel turned hipster speakeasy, not a football command center. Venables is Oklahoma’s coach. His office is hardwood floors, vases stuffed with fresh flowers, rugs designed in ornate patterns, a leopard-print coffee table, a collection of Air Jordan sneakers and another collection of Rolex watches.

An oversize hourglass sits on the end table to Hurts’s left. Venables keeps it there for meetings, denoting time and its importance. Hurts can relate. The men share a like-sands-through approach and a history that embodies Hurts’s always-doubted, never- thwarted career arc. The game before Nick Saban benched him at halftime of the 2018 national championship, Hurts cleaned up Venables’s Clemson defense. Their parallel paths to this day, this meeting, this office hang as heavy as the humidity thickening the air. “We wasn’t friends years ago,” Hurts says. “We friends now.”

They pivot into friendly topics: the size of margins in big-time football games (BV: very small; JH: so small), standards (critical), time management (how to obtain a master’s while becoming an MVP candidate), offensive football (the Air Raid and its evolution), fathers (Hurts’s, a cornerstone; Venables’s, largely absent), mothers (prominent for both), transitions (that led both to OU; different times, same place), Hurts’s recovery (on pace, heavy on soft-tissue massages) and commercial flights vs. private ones (an obvious shared preference). Even Hurts’s sister’s prom comes up. “She’s dating some guy,” he spits out like burnt cheesesteak. Venables asks about the Super Bowl, the pain from almost. Hurts sidesteps the question. Instead, he reflects on the night the Eagles drafted him. He never expected to land there, given that the team had just rolled up a Brink’s truck to Carson Wentz. Hurts shrugs. “My phone rang. I answered it. Game on from there.”

He didn’t know their thinking then. Both Roseman and Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie viewed Hurts’s response to his benching at Alabama as a key to his potential. Roseman looked at the best quarterbacks in pro football—Brady, Rodgers, Mahomes, Prescott. Hadn’t all met seemingly insurmountable obstacles? Didn’t it matter how they surmounted them? Hadn’t Hurts done so better than any of them in college? After deciding to select Russell Wilson in the third round of the 2012 draft, only for Seattle to nab him 13 spots before they picked, Roseman says he planned, all along, to take Hurts in the second. “We were obsessed with Jalen,” Lurie says.

Venables interjects. “Everything you’ve done in your career has been uncomfortable.”

Hurts nods, simply and dispassionately, then launches into self-awareness, echoing a pair of philosophers: Socrates (know thyself ) and Drake (know . . . yourself). Finding gratitude allowed for peace of mind. Improvement motivated more than slights. He sought others to help him improve, then thanked them—appreciative notes/texts/conversations as part of his process.

Two weeks after graduation, Hurts is asked whether he noticed either the hourglass, or the sign next to it that read believe. “Right away,” he says with a wink.

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

Hurts leaves the office, graduation crew in tow, heads outside and climbs into an SUV. There’s no time, and yet, it’s time—to eat. Hold up. Is this . . . an actual . . . departure from the itinerary? A humanization of The Robot? Hurts flashes a weary smile before speeding away for chicken strips.

Lessons defined Hurts’s first two NFL seasons. His rookie year, 2020, was a disaster, as he went 1–3 after taking over for Wentz. His second season was better—the Eagles snuck into the playoffs and lost in the wild-card game—but uneven. The following spring, Ted Rath, the Eagles’ VP of player performance, bumped into Adam Dedeaux, the quarterback whisperer who runs 3DQB in Southern California. Rath hadn’t planned to push a Hurts partnership, but he said to Dedeaux, “Honestly, if you’re interested, maybe you want to take on Jalen? He’d really benefit from spending some time with you.”

This was no criticism. Dedeaux routinely helps franchise cornerstones maximize their immense gifts. With a 1-year-old at home and too many existing clients already, he didn’t have time. But he made a phone call, anyway. Typically an initial call with a potential client is a short conversation that forms a starting point for the work ahead. His conversation with Hurts lasted 52 minutes. Dedeaux loved Hurts’s specificity, how his football memory bordered on photographic.

Hurts trained at 3DQB before last season, while Roseman rebuilt the team around him. Dedeaux noticed something immediately: Hurts could throw. He arrived with a skill set that needed tweaks and refinement, but not a mechanical overhaul. If anything, he was too robotic, restricting his natural gifts. They focused on fluidity, making Hurts 2.0 a more creative and improvisational QB who at times reminded Dedeaux of Aaron Rodgers. He invited Hurts to the beach and for barbecues in his backyard, and encouraged casual games of catch. Hurts awed Dedeaux in those settings. “Apply that,” Dedeaux told him.

Not only did Hurts listen, but he also told the staff to stop relaying instructions in the moment. “I need to hear you less,” he said. Dozens of elite throwers have descended on 3DQB, but only one other had expressed that sentiment: Drew Brees.

Fluid szn ramped up with nontraditional drills designed to force Hurts into uncomfortable body positions; he’d throw while bending, twisting, running and squatting down. They used weighted footballs, tennis rackets and baseball bats, all designed to normalize chaotic conditions. They’d hand Hurts a bat, for example, and tell him to forget fundamentals and swing as hard as possible. When he did, his body and feet still ended up in a natural position—even if it wasn’t what most would consider an ideal stance. His instincts led his body to the right place. “I felt completely disconnected,” he told them. “Now I feel powerful.”

These were, undoubtedly, incremental improvements. But the best NFL players live inside those margins, making gains, however minuscule, where peers cannot. Hurts improved in dozens of small ways. Like throwing while sprinting to his right, a simple brain-body connection from his infield days. These gains portended much more. Hurts walked with an easy gait. He wasted no movement. He used tempo.

“There’s another level of his game from a throwing perspective and understanding his body that he hasn’t tapped into yet,” Dedeaux says. “There’s still even more.”

Roseman’s acquisition of All-Pro wideout A.J. Brown in April 2022 helped Hurts apply those lessons, in part because of their relationship. Hurts, who became close with Brown as he tried to recruit him to Alabama, is the godfather to Brown’s daughter and, in this instance, he did push for a trade, intent on supercharging the offense. Brown combined with DeVonta Smith, Hurts’s Alabama teammate, to form one of the league’s most imposing receiving rooms. Brian Johnson, one of Hurts’s dad’s former players, became the Eagles’ QB coach, which bolstered both familiarity and continuity.

This spring, Hurts focused on consistency in lower-body mechanics. The Eagles promoted Johnson to offensive coordinator, after Shane Steichen left for the Colts’ head coaching job. Rath flew to California for an update. He found Hurts somehow, some way, even more metronomic, but with that natural fluidity built in.

“There’s no bar for this kid,” he says.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

On graduation day, Hurts is three months removed from the best (and worst) stretch of his career. Week 15 found the Eagles in Chicago, on an ominous Sunday featuring high winds and vicious cold. Philly had solidified into the NFC's best team, but late in the third quarter, Hurts went down after an innocuous-looking tackle. He grimaced on the near-frozen Bermuda grass at Soldier Field, the Eagles' season suddenly threatened. Jordan Mailata, the team's left tackle, jogged over.

“Stay down,” he said. You’re hurt.”

Mailata wasn't wrong. But Hurts ignored the pain rocketing through his throwing shoulder. While staring up with trademark urgency, he shouted, “Get me the f---up!”

Hurts stayed in and completed a short pass before walking slowly to the sideline and announcing, “My S—'s broke.”

"Can you be more descriptive?" Rath asked, attempting to lighten the apocalyptic mood.

Hurts pointed to the organization's most valuable joint. “My shoulder,” he said. “I felt it. I just broke my collarbone again.” Hurts had done that at Alabama. He couldn't throw at all afterward, and now the pain felt sharper. The training staff huddled around, but Hurts waved them off.

“I’m not f---ing coming out,” he said.

Hurts earned his second degree in May, a master’s in human relations. Consider the calculations necessary in that instant. Hurts knew the Eagles desperately needed to win for playoff seeding. On the other hand, he knew his season might be over. He didn't miss a snap, going 6-of-9 after the injury and snagging a critical win. "I felt serious pain. Pain I've never felt," he says. "It wasn't easy. Being able to overcome everything that went on in that game, it took a lot."

Pity the fool who dares stand between Hurts and his intentions. The public knew little, if anything, of what had transpired. He sat out the next two games, but in Week 18 against the Giants and throughout the entire postseason, his last name doubled as an injury report. Jalen hurts. Wasn’t this similar to Jordan’s Flu Game? To Bryant’s hobbling back on the court to shoot free throws with a torn Achilles? Hurts doesn’t thump his chest. He also doesn’t disagree. Bryant, however, didn’t finish his game. Hurts did.

The ultimate diagnosis—a sprained SC joint—complicated the short term. No one on the Eagles’ training staff, nor any consultants they spoke with, had ever heard of someone playing with that specific injury the same day they were injured. Illogical chatter around Hurts defined the first half of his season—that Philadelphia was, essentially, so talented as to make his job easy. But the two games the Eagles lost with- out him proved his value. His MVP candidacy was bolstered by not playing.

Due to his Week 17 return, Philadelphia beat the Giants to nab a postseason bye. But when Sirianni centered his speech before the conference championship on overcoming adversity, Hurts chose not to identify with a theme that most embodied him. The intention: to not look back.

Before leading Philly onto the field, he asked his teammates, “How do you want to be remembered?” To Saban, Hurts’s demeanor brings to mind a commercial. Hurts’s first college coach cannot remember the product but recalls the tagline: “Be comfortable in your skin.” That’s Hurts, self-assured and self-reliant. “He had to make himself into a never-satisfied guy, until he got to where he is right now,” Saban said early in Super Bowl week.

As the game approached, Jalen’s older brother, the one who called him The Robot, hoped his latest response to a potentially devastating event would show that he was, in fact, human. His MVP-caliber performance screamed the opposite. Didn’t matter. Correcting perception never fell under intent. Hurts wouldn’t let that happen. “The mind has a hell of a lot of power,” he says.

Jalen heals.

John Baker/Oklahoma Athletics

On graduation day, inside the Lloyd Noble Center, lights dim, stragglers hustle into seats and “Boomer Sooner” is sung, said and screamed. Soon, the academic equivalent of a hype video plays on big screens.

Thus begins the 131st commencement in OU history. There are bagpipes, a red carpet, TV cameras, caps, gowns, flags upon flags, a bald eagle statue, headdresses, banners, reserved seating and the Eagles’ quarterback. Amid all the pomp and circumstance, there are at least a dozen renditions of “Pomp and Circumstance.”

The pageantry isn’t for Hurts, specifically; it only unfolds that way, as Joseph Harroz Jr., university president and the most Boomer of all Sooners, begins his speech.

“So, class of 2023, what happened?”

Harroz pivots to the one subject sure to unite his eager audience. It’s football, naturally. “Tonight, he becomes a master’s graduate. Please join me in congratulating . . . Jalen Hurts!”

What happened? is the perfect question for Hurts, too. A lot. Everything. More than expected. Not nearly enough. The crowd rises, cheering politely at first, then ramping into a roar, as if he is scrambling toward the end zone at Memorial Stadium.

Diploma in hand, Hurts exits the arena and hops back into the SUV to head to Houston for three major events scheduled for the next day (graduation party, Mother’s Day, sister’s prom). The future seems to crystallize at that moment, as the master plan continues to unfold, as doubters become converts, as the Lombardi Trophy that eluded his grasp last season becomes obtainable once more.

Hurts remains the same person who arrived in Norman four years earlier. Mostly the same person, anyway. That’s the thing about The Robot, the most intentional superstar in sports. Intention doesn’t rule out change, as long as change bolsters intention. Just like on graduation day, when, after the reboot, he’s back on schedule, accompanied by those who do believe in him, plotting another plan.