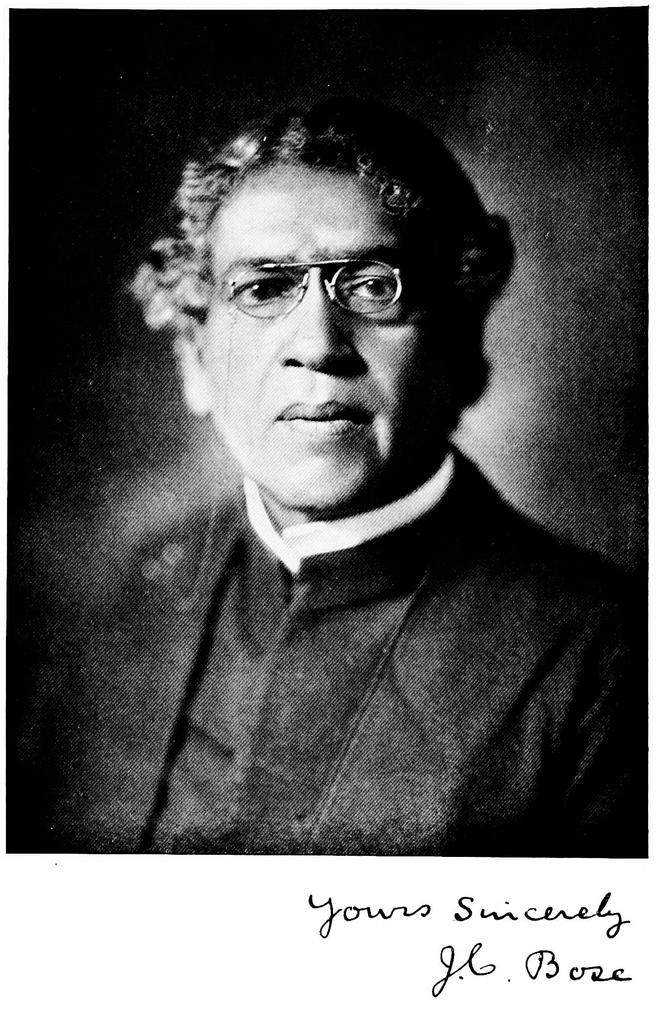

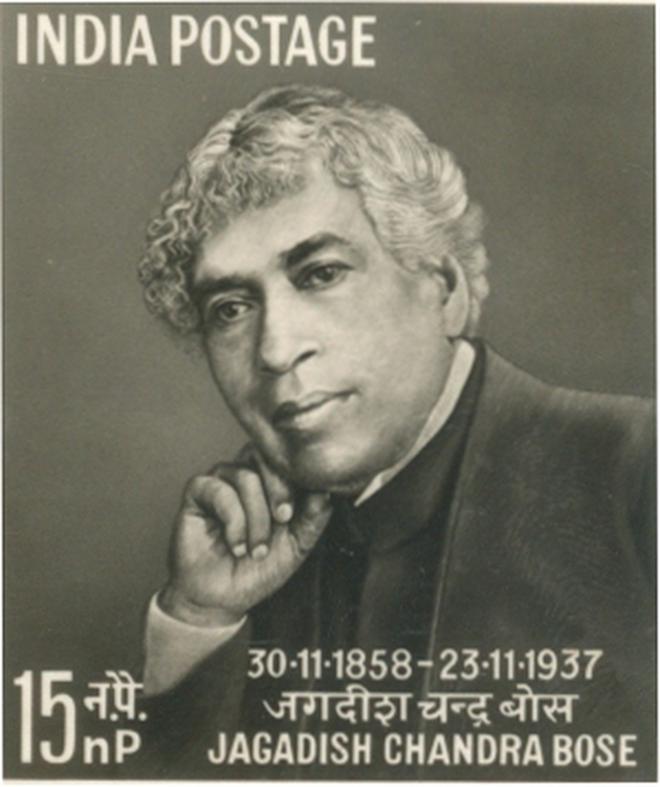

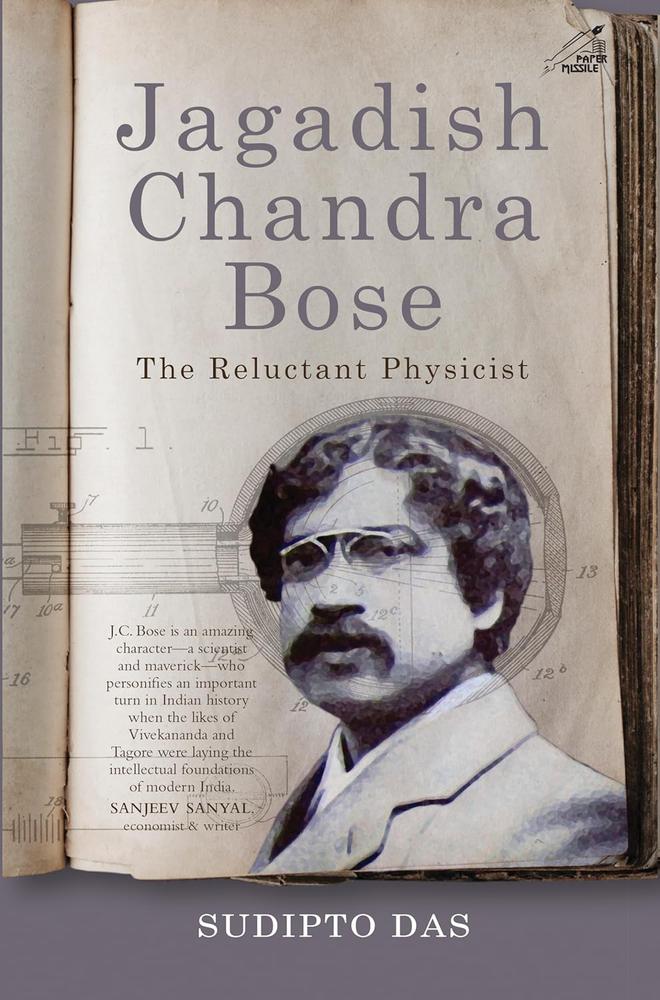

Jagadish Chandra Bose was a polymath, a pioneer in wireless communication and plant electrophysiology. In 1917, he set up the Bose Institute in Calcutta dedicated to scientific research, but as a scientist he was misunderstood, as is clear from this letter to Patrick Geddes, written in 1917: “I do not belong to any special fold — the physicists think that I have given up physics and gone over to the botanists; the vegetists think that I am the physiologist and so on...” In his new book, Jagadish Chandra Bose: The Reluctant Physicist, Sudipto Das profiles Bose and his contribution to science. Edited excerpts from an interview:

Your book is divided into four parts exploring the theme of unity. Can you elaborate on the significance of this theme in the context of Jagadish Chandra Bose’s life and contributions?

Bose belonged to the Unitarian Brahmo fraternity, like Rabindranath Tagore, Raja Rammohan Roy and other eminent Bengalis. Brahmoism was founded on the principles of Advaita Vedanta, the genesis of which can be captured in these words from a verse from the Rig Veda: “Ekam sat, vipra vahudha vadanti” or there exists only “One, the wise call It variously.” At its core is the universal concept of unity in everything. Bose’s pursuit of unity leads him to find a commonality in life in a plant and human. He prophesied that plants, too, like humans and animals, can feel pain, thus creating the foundation of new disciplines like plant-neurobiology and plant cognition.

Bose’s relationships with Swami Vivekananda, Tagore, and European figures play a pivotal role in your book. How did you explore the intricate nature of these relationships?

Vivekananda and Tagore were both global citizens, as was Bose, whose life and work had a universal appeal, thus making his associations with westerners natural and spontaneous. Though a staunch nationalist, thriving on the idea of achieving India’s self-reliance through science and technology, he always believed that India and the West should go hand in hand in all their endeavours. That was a deviation from the anti-British sentiment that was brewing in India at that time. No wonder, some of Bose’s biggest patrons were from the West. These relationships tell of his belief that knowledge and human progress are a collective affair, not fragmented, or divided between borders.

How did you uncover Bose’s overlooked role as a radio inventor in the late 1990s, and what methods did you employ to navigate historical records for this significant revelation?

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers brought out a series of publications in the 1990s unearthing the truth that eluded us for many decades. It was settled that Bose had set up one of the world’s first functioning wireless systems before Marconi, and that Marconi later used Bose’s radio receiver to receive the first trans-Atlantic wireless transmission in 1901, without giving any credit to Bose.

How did you portray him as a multifaceted personality, and what challenges did you face?

From the beginning, my aim was to get under the skin of the person and explore the man he was, with his share of virtues and vices, rather than present him only as a scientist. That naturally brought out his multiple facades, from a hunter chasing tigers in the Terai jungles to sculling in the freezing waters of the Cam River in Cambridge, writing the first Himalayan travelogue in any language, influencing Tagore to write poems inspired by stories of love and sacrifice from Indian history and mythologies, or even surreptitiously keeping quiet when, he perhaps knew, lab aides planted by Sister Nivedita in Presidency College were regularly taking out explosive materials from the laboratory to make bombs.

Your book mentions a meeting between Einstein and Bose in 1926. Can you share more insights into this encounter?

Bose and Einstein were both members of the League of Nation’s International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, a precursor of UNESCO, along with many other Nobel Laureates like Hendrik Lorentz (physics), Henri Bergson (philosophy), and Marie Curie (chemistry). Bose attended the committee’s first meeting in Geneva in 1926. The world had not yet recovered from the horrors of the First World War, and Bose’s talks about “unity” in everything, even in plants and humans, struck a chord. Einstein was so impressed with Bose’s lecture at Geneva University that he reportedly said, “If only for a single one of his many discoveries, Bose should have a statue erected to his memory.”

How do you see Bose’s legacy extending beyond the scientific realm, and what message do you hope readers take away from his life?

I wanted to present a personality that worked towards making India a self-reliant country, not by berating anyone else but by cooperating with everyone and seeing unity in the bewildering diversities all around. I feel that’s his legacy which is even more relevant today.

Jagadish Chandra Bose: The Reluctant Physicist; Sudipto Das, Niyogi Books, ₹795.

The interviewer is a Bengaluru-based management professional, literary critic, and curator. He can be reached at ashutoshbthakur@gmail.com