As they watched footage on the news of Tonga’s “once-in-a millennium” volcanic eruption last week, Matt Urey and Lauren Barham became filled with a sense of dread.

The couple from Richmond, Virginia, could sympathise with the plight of the South Pacific nation more than most, having only just survived a catastrophic eruption on the same Ring of Fire volcanic chain that encircles the Pacific Ocean.

They knew all too well what it felt like to have life altered in an instant by the frightening force of mother nature, and painful memories came flooding back.

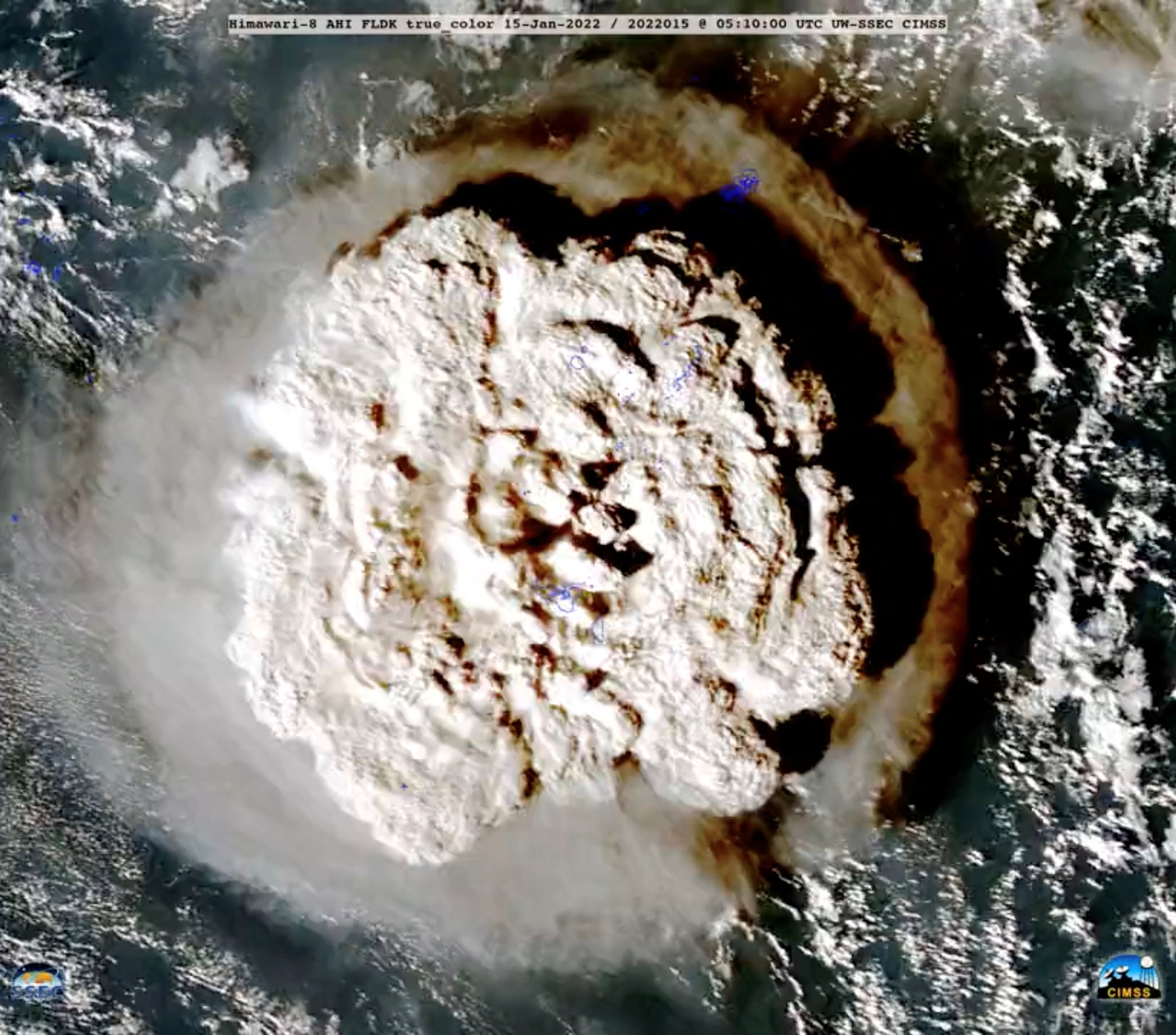

“It really bothered me,” Mr Urey tells The Independent of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption that sent spectacular plumes of smoke, ash and gas into the sky and set off tsunami alerts from California to Japan.

On 9 December 2019, the couple were on their honeymoon cruise aboard Royal Caribbean’s Ovation of the Seas when they took a shore excursion to New Zealand’s White Island volcano.

They were led to the crater’s edge to experience the dramatic, lunar-like scenery. Moments later the volcano erupted, and the couple became submerged in burning ash and pelted with rock, leaving both with life-long physical and emotional scars.

Twenty-two people were killed in the eruption and dozens more were left with catastrophic burn injuries.

Three weeks before the eruption, New Zealand’s geological hazards agency Geonet issued a level two alert for the volcano, which is one step below an eruption event.

In fact, scientists had been warning for more than 20 years that “frequent explosive eruptions present an obvious threat” to the thousands who visited White Island each year, according to multiple court filings.

Mr Urey and Ms Barham are among survivors and family members of the victims who are suing Royal Caribbean International for gross negligence causing loss of life and physical and emotional injury.

“We wouldn’t have gone there if we had known it was so close to an eruption,” Mr Urey tells The Independent.

“It was a failure from top to bottom.”

‘We literally took off running for our lives’

Honeymoon pictures from before the eruption show Mr Urey and Ms Barham taking in Sydney’s famous Opera House, visiting the city’s aquarium, and at the top of the Southern Hemisphere’s highest building, the Sky Tower in Auckland, New Zealand.

“I really wanted a relaxing honeymoon,” Ms Barham says.

They were fit and active, but not interested in adventure tourism.

Upon arriving at the port of Tauranga on New Zealand’s east coast, the newlyweds boarded a bus for Whakatane 90km away where they boarded small inflatable boats for the 90-minute journey to White Island.

Within minutes of landing on White Island, that anticipation had turned to fear after they overheard a guide say the volcano’s alert level had been raised and the tour would have to be cut short. The mountain had recently received a level two alert warning and was approaching level three - meaning it could erupt at any moment.

The couple were given gas masks to combat the toxic smoke and hiked to the edge of the crater, posing for photos as the volcano’s mouth smouldered a few metres away.

At 2.11pm on 9 December 2019, they heard a deafening crack.

“We heard our tour guide shout run, and that was when it all hit. We literally took off running for our lives,” Mr Urey said.

A thick plume of smoke rose 3.7 kilometres (12,000 ft) into the air, blotting out the sun and bringing burning rocks and a toxic cocktail of poisonous gases streaming back down to earth.

“There was nothing you could do, but hang on and hope to survive,” Mr Urey said.

They huddled behind a rocky outcrop, as burning ash rained down all around them.

Ms Barham said she held on tightly to her husband as they slowly became buried underneath the ash.

“At that point I was sure I was going to die,” she tells The Independent from her home in Virginia.

“I just kept telling Matt ‘I love you’. I just held on to him because I wanted our bodies to be found together.”

Ms Barham’s gas mask was blown off in the blast, while Mr Urey said his became filled with ash and smoke, momentarily blinding him.

“You have the extreme heat, you’re being pelted with rocks out of the volcano, you could not see any daylight. It was pure terror.”

When the eruption stopped two minutes later, Ms Barham was in shock and unable to walk, and Mr Urey guided her back to the jetty.

They found a single dinghy waiting to take the injured survivors to safety, and had to make a decision whether to climb aboard the small inflatable boat or wait for a helicopter to arrive, unsure if another eruption was coming.

“Everybody was panicking trying to get off there. It was a free-for-all,” he said.

“There was this rusty metal ladder leading to the boat, and as I grabbed on it my hand just slid because all the skin was peeling off my fingers.”

They found a spot on the crowded boat, and endured an excruciating 90-minute trip back to the mainland as Ms Barham passed in and out of consciousness.

“We were getting blasted by saltwater and laying in the sun, while burnt to a crisp. It was absolutely agonising,” he says.

A crewmember washed the ash off their bodies, which they believe saved them from even worse burn injuries.

Mr Urey said he was still running on adrenaline and rode in the ambulance back to Whakatane Hospital - a small regional medical facility unequipped to deal with a mass casualty event.

As Ms Barham was taken into an intensive care room, he was led into a separate room and wrapped in cling film.

It would be the last time they saw each other until February when they were reunited at a hospital in Richmond, Virginia.

Ms Barham was medevaced 300km (180 miles) north to Auckland where she spent three weeks in a coma. Her airwaves had been burnt from the ash and she suffered a lung infection.

Ms Barham suffered 23 per cent burns, including to her hands, neck and face.

Mr Urey was flown to a hospital 1,000km (600 miles) away in the city of Christchurch in the country’s South Island, where he spent 11 days in a medically-induced coma.

Photos taken soon afterward show Mr Urey’s burn marks forming a patchwork of bright red scars on his back, chest and legs. He sustained burns to 54 per cent of his body.

“That was our honeymoon and we spent the majority of it in a coma hundreds of miles apart,” Mr Urey said.

New Zealand’s hospital burn units were overwhelmed in the days after the eruption and surgeons had to order in 120 square metres (1,290 square feet) of human skin from overseas.

Amid the confusion, survivors and family of the injured struggled to find out where their loved ones were and who had survived.

In all, 20 tourists died; 14 from Australia, five from the United States, and a German national, along with two local tour guides. It took days for some victims to succumb to their injuries. Many more suffered “life-altering” injuries.

Florida attorney Mike Winkleman is representing the Ureys and several other US-based victims in a lawsuit against Royal Caribbean and told The Independent the cruise company had failed to alert his clients about the risks.

“Passengers weren’t fully informed about what was going on the island and were not able to make an informed decision,” he said.

“Just about all the passengers have said ‘if I had known about the heightened seismic activity, I never would have set foot on White Island’,” he said.

Royal Caribbean International declined to comment to The Independent.

‘Powder keg’

Australian Stephanie Browitt is another survivor who is suing Royal Caribbean.

The 25-year-old boarded the Ovation of the Seas cruise ship in Sydney with parents Paul and Marie, and sister Krystal, a veterinary student. They were celebrating Krystal’s 21st birthday, and made a spur of the moment decision to book a day excursion to the volcanic island, except for Marie, who stayed on the ship due to a medical condition.

When the volcano blew, Stephanie had just snapped pictures near the centre of the island with her father and sister, and was struck by burning ash and rocks.

“Covered with burns and barely able to move, Stephanie staggered toward the jetty, with other passengers screaming and grabbing at her legs as she went,” according to a lawsuit filed in Florida’s Miami-Dade County Court.

“She made it to the jetty, where she waited on the hot ground for rescue. Every 15 to 20 minutes, she could hear her father calling her name and she realised he was trying to help her stay awake. She shifted position periodically as the hot, ash-covered ground burned her side and back.”

Krystal never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead at hospital. Paul died after spending several agonising days in hospital. Stephanie woke from a coma two weeks later with third-degree burns to 70 per cent of her body.

Florida attorney Rebecca Vinocur, who represents the Browitts, says tourist excursions to the “powder keg” island could not have been safe under any circumstances.

Royal Caribbean “compounded its error” by ignoring warnings of heightened risk and failing to inform passengers of White Island’s history of eruptions, Ms Vinocur says in the lawsuit.

They have accused Royal Caribbean of gross negligence causing the wrongful deaths of Paul and Krystal, and physical and psychological injuries to Stephanie and Marie.

Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd, one of the largest cruise companies in the world, is registered in the West African country of Liberia and maintains its corporate headquarters in Florida.

After the Browitts filed their lawsuit, Royal Caribbean attempted to get the case shifted to Australia, claiming terms in their ticket agreement meant any disputes could only be tried in the state of New South Wales.

However, a federal court in Australia ruled in June last year the appropriate jurisdiction was Florida, where the company’s headquarters are based.

That ruling opened the door for Australians to file lawsuits in the US courts, and Mike Winkleman said several more clients had joined the litigation. More details of the passenger’s suffering emerged in newly filed court documents.

“The potential for a significant recovery is much higher here in Florida than it is in Australia,” Mr Winkleman told The Independent, as the case will be heard by a jury.

He is also representing several plaintiffs including the family of Mayuari and Pratap Singh, an Indian-American couple from Atlanta, Georgia, who were killed in the eruption.

Mr Winkleman told The Independent: “Their big defence is an act of God, there’s always an element of that. But when there’s red flag after red flag there comes a point when you have to do something about those red flags.”

He says his clients accept there are some inherent risks with visiting an active volcano.

“What the law requires here is that Royal Caribbean or any cruise ship operators give a warning to its passengers about risks it knew about or that it should have known about.

“They literally make tens of millions if not hundreds of millions of dollars, marketing, promoting the tours - everything related to excursions. My clients want to see better warning signs and greater responsibility shown by cruise companies.”

The Ring of Fire

New Zealand’s explosive geology, a key feature of the country’s physical beauty that used to attract four million annual visitors before the Covid pandemic, has long been both a blessing and a curse.

Sitting on the Ring of Fire chain astride the Pacific and Indo-Australian tectonic plates, New Zealand sees frequent, violent earthquakes and occasional volcanic eruptions, Auckland University Professor of Volcanology Shane Cronin tells The Independent.

“Volcanoes from the Aleutians to Alaska and from Tonga to New Zealand are all related to the same general process. Each volcano along this ring, however, operates independently of the other volcanoes in terms of its magma accumulation and eruption frequency and timing,” Professor Cronin says.

“In addition, the combined impact of volcanoes and earthquake motions have generated a series of spectacular lakes, mountains and geothermal areas – all of which are major tourist attractions.”

Filmmaker Sir Peter Jackson employed that dramatic scenery to bring Tolkien’s Middle Earth universe to cinema screens in the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

White Island sits 48km (30 miles) off the coast of the Bay of Plenty, one of New Zealand’s most scenic and impoverished regions.

New Zealand’s indigenous Maori have lived in the area for about 700 years, and call the island Te Puia o Whakaari, which translates to The Dramatic Volcano.

It received its English name from explorer Captain James Cook in 1769 for the white clouds hovering around its peak.

According to information from New Zealand’s Ministry of Civil Defence, White Island erupted at least 10 times in the past century, including a deadly 1914 eruption that killed 11 sulphur miners on the island (The only survivor was the mining company’s cat, who earned the nickname Peter the Great.)

New Zealand’s deadliest recorded eruption occurred in 1886 when the North Island’s Mt Tarawera blew, burying villages in the area, destroying the famed pink and white terraces of Lake Rotomahana, and killing an estimated 120 people.

White Island experienced the longest eruption episode in recorded history between 1975 and 2000, as active vents in the mountain’s craters emitted volcanic ash.

According to Geonet, the volcano experienced a succession of steam and sulphur explosions in 2012, 2013 and 2016 that dramatically reshaped the volcanic cone, causing landslides and the formation of a new lake on the island.

Despite the regular eruptions, volcanic activity on White Island is notoriously difficult to predict, says Professor Cronin.

Small amounts of magma are continuously being fed into the island’s conical peak, he says.

“The magma rises very slowly to the surface at this volcano so it is not erupting with large volumes all the time, but it does have a continuous hot crater area with hot springs and fumaroles. It also builds up gas pressure regularly.”

And yet none of the island’s explosive history was explained to the passengers, the lawsuits allege. While it did advertise that White Island was an “active” volcano, this only indicates that there had been at least one eruption in the past 10,000 years.

The alleged collective failure has also led to criminal charges against several Government agencies, tourism operators and company directors in New Zealand.

WorkSafe, the country’s workplace health and safety regulator, has charged GNS Science with failing to “effectively communicate” the dangers of volcanic activity.

White Island’s owners Andrew, James and Peter Buttle and their company, Whakaari Management, also face criminal charges, along with several tour companies including White Island Tours, Volcanic Air Safaris and ID Tours New Zealand.

All have pleaded not guilty, and a criminal trial is expected to take place later this year. Each organisation faces a maximum fine of NZ$1.5m, and the individuals could be fined up to $300,000.

Mr Urey and Ms Barham are assisting New Zealand police with the criminal case and say they are expecting to give evidence via videolink at trial.

“It’s been hard on us, especially when they are pleading not guilty,” Ms Barham says. “I just wish they would take accountability for what they did.”

Mr Urey agreed, saying there had been a collective failure.

“White Island Tours knew that island better than anybody else. They should have known not to send us there.

“And at the very minimum, Royal Caribbean should have told us before we got off that cruise ship, ‘hey this volcano is at a heightened level of activity, you might want to double check if you’re really willing to accept this risk’. Instead of sending us on our merry way without saying a word.

“Any one organisation stepping up could have stopped this tragedy.”

In October, Nature magazine reported that some in the scientific community fear that prosecuting a science agency over the information it releases could have a “chilling effect” on an organisation’s ability to give the public accurate and timely advice on natural hazards.

‘It’s like ageing 40 years overnight’

More than two years after the eruption, Lauren Barham is still undergoing monthly operations for her injuries at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Initially she struggled to even hold a knife and fork.

As a lab technician at a hospital, she says the ongoing skin grafts are gradually helping her to recover more mobility and strength in her hands.

“I understand that I’m going to have scars forever, but I just want my range of motion to be better.”

Mr Urey works as a mechanical engineer at a company that makes flame resistant clothing, and says one of the hardest things to deal with has been the loss of sensation on his grafted skin.

“It’s like ageing 40 years overnight,” he says.

“Every joint is stiff, your skin constantly tightens up. Every morning you spend 20 minutes trying to get your skin to move, and we both apply lots of lotion every day.”

In his spare time he likes to build and fix things. “I drop screws and nails constantly, because I just can’t feel them like I used to.”

Mr Urey used to be an avid runner, but now his body is unable to cool down properly because his grafted skin doesn’t sweat.

“That’s one hobby that is never coming back which hurts, because that used to be my stress relief.

“This just drags on and on.”

Complicating their recovery has been Covid – the couple are fearful of what an infection could do to their immune systems.

They are holding on to the hope of starting a family one day, and are about to become an aunt and uncle for the first time.

“There’s still not a day that goes by when I don’t think about the eruption,” Ms Barham says.

“I have days when I really struggle emotionally. But I also have a new appreciation for life now.”

She hopes by taking legal action that White Island is never opened to tourists again.

“That place should just not be open at all. It’s too unpredictable.”

Stephanie Browitt suffered burns so severe that her eight fingers had to be amputated at the second knuckle. She has had more than 20 surgeries and faces a long, slow recovery.

Her attorneys did not respond to a request for comment, but Ms Browitt has shared her recovery journey in a series of inspiring posts on social media.

Ms Browitt, who still wears a mask for her injuries, has written candidly about how simple pleasures like enjoying a restaurant meal or wearing a dress in public have helped.

On the second anniversary of the eruption, her “burnaversy” as survivors often call it, Stephanie posted a moving tribute to her family, and to celebrate the many hurdles she had overcome.

“Today marks two years of accomplishments but also loss, pain and never ending grief. I miss and yearn for my family everyday. I love you so much dad and Krystal, so much it kills me.”