In 2019, the 50th anniversary of Jethro Tull’s trailblazing Stand Up presented the opportunity to look back at the band’s late 60s development. Guitarist Martin Barre told Prog how close he came to never being in the band – and explained what he took from the financial success the album gave him.

How did you end up joining Jethro Tull between This Was and Stand Up?

The connection was through flute playing. ian and myself were pretty much the only two people in England playing flute in a rock style. I knew about him because I had friends who were musicians who had been to see Tull at the marquee and other places, and had excitedly told me there was somebody else doing what I did – probably a lot better!

Then my band, Gethsemane, supported Tull at a club in Plymouth. We found we had a lot in common, we listened to them, they listened to us. and that carried through to when I heard that Mick Abrahams had departed and they were looking for another guitar player.

Did you approach the band or did they approach you?

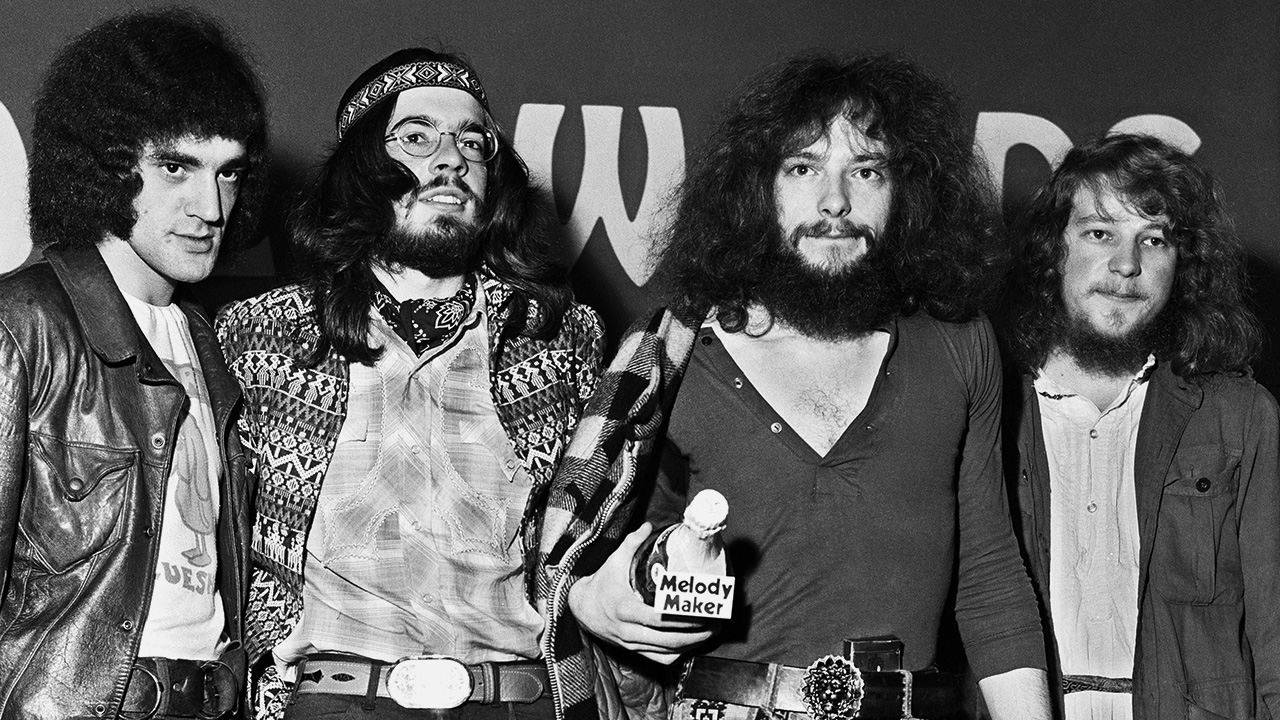

It was a bit of both. They were looking at options, but they’d forgotten my name and the name of my band, so they had no way of getting in touch with me. I heard about an advert in Melody Maker where they were looking for another guitar player, but I didn’t have the courage to phone up, so I left it.

Then at a very last gig Gethsemane played before we split up, this guy approached the stage and said, “You’re Martin, aren’t you? My name’s Terry Ellis. Can you give me a call in the morning?” He handed me this card, and I’m like, “Oh my god.” It was very exciting. And if he hadn’t caught me at that last show, he probably wouldn’t have found me at all.

Did it feel like you were joining a band on the way up?

Definitely. It was everything I’d worked for. I’d spent three years with my old band trying to be successful, and we’d given up. For me, this was a like a door had opened to this whole world. Finally I had a chance to do something with music.

And I wasn’t a particularly studied musician. We were all still learning to play our instruments. But there was the excitement of finally having the opportunity to play good music and great gigs with a great band. As far as I knew, it was going to change my life for a few weeks or a few months, or maybe a year. But even just that was exciting.

The first single you recorded with Tull, Living In The Past, was a hit. Did you think, “Wow, I’ve made it”?

It was never like that. The first few shows were really bad. The audience were expecting 12-bar blues like they’d always heard; when they heard the songs we’d written for Stand Up, they weren’t expecting it and most of them didn’t like it at all. It was a very negative response.

We were all like, “Oh dear, is this going to work?” Ian was very nervous about this big step he was taking in his writing, and my neck was on the line – if they didn’t like this music, I was going to be out of there.

What was the turning point?

A gig at Manchester University. All the previous gigs had had a very lukewarm reception, and at this point we were all getting very nervous. But that night they loved it. I remember coming offstage and smiling, and Ian was smiling. We just thought, “Okay, the first step has worked.” and the next thing, we were supporting Hendrix in Europe.

What do you remember about making Stand Up?

It was exciting. The songs were new; the direction was new; there was nobody else playing that style of music. We all had elements of naiveté – we were all learning how to play that music together and try and be better players. It was a real discovery for us. It was very spontaneous – a lot of nervousness and anxiety because it was an important album.

We were serious, but then Jethro Tull always took ourselves seriously – maybe too seriously in retrospect. We weren’t like other bands: we didn’t party, we didn’t go crazy. We were always on tour, always writing.

That must have made it interesting when you supported Led Zeppelin in America, given that you weren’t interested in the kind of behaviour they were into...

Oh, I was! But only as an observer. It was like being a reporter with a notebook going, “No! Wow!” It was hilarious. We had all the fun but we didn’t have to go through the lifestyle.

Why did you recoil from it?

I dunno. There’s probably something wrong with me.

What did American audiences make of you?

They loved it. they were so hungry for British music. it was all laid out in front of you – if you messed up the process of getting through to them, you were pretty bad. And they didn’t know what to expect. A lot of people thought we were old men because they’d seen the cover of This Was and they thought the photograph was real: “Oh wow, we thought you were in your 60s.”

We’d been on £50 a week, with meals and hotel rooms in when we were on tour – and we thought we were in heaven with that

How did Stand Up change your life?

Not long after it reached No.1, Terry Ellis got us in a room and said, “Right guys, you all need to buy a house.” Before then, we’d been on £50 a week, with meals and hotel rooms in when we were on tour – and we thought we were in heaven with that.

So when Terry said that, we just stared at him: “But Terry, why would I buy a house when I’ve got a nice flat in Shepherd’s Bush? It’s a bit damp and it smells, but it’s cheap.” And he just said, “No, you’ve made some money – I advise you to buy a house.” “Right, so how do we do that...?” We really had no clue.

Other than financially, how did it change your life?

It gave me freedom. It meant i could listen to music and play guitar whenever i wanted. But all along we were just touring like crazy – this express train was still going. Although i did get a house as a base in England, I was never there.

There was never a time when you could just sit back and think about things. There was constant pressure to improve because we were playing with every whizz kid and every hotshot band in the world – Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Hendrix, Paul Butterfield, Chicago. That put pressure on me because I wanted to get better – I needed to survive.

How do you look back on it now?

I love it. I’m doing a 50th anniversary tour this year – a big celebration. And in my mind, Stand Up is the centre of it. Those songs are so powerful; it’s the 21st century; I’m playing For A Thousand Mothers, and it’s still an amazing piece of music. it still really works.