The brand new issue of Classic Rock magazine is a celebration of all things 1984 – the landmark albums, cult classics and great music that came out exactly 40 years ago. In this exclusive extract, we look at Street Talk, the solo debut album from Journey frontman Steve Perry and an all-time AOR classic.

It was a golden year for melodic rock. In January 1984 came the debut album from a young band out of New Jersey named Bon Jovi, and in the months that followed, so many other great albums arrived. Survivor, with new singer Jimi Jamison, hit a new peak with Vital Signs. Bryan Adams released Reckless, the album that would make him a superstar. Pat Benatar’s Tropico was a thing of beauty.

There were also fine albums that somehow flew under the radar or slipped through the cracks, but which later become cult classics – Dakota’s Runaway, and self-titled debuts from Giuffria, White Sister and Boston spin-off Orion The Hunter.

At the other end of the spectrum there were huge hit singles for Night Ranger with Sister Christian and John Waite with Missing You. And at the end of the year came the release of two monumental power ballads, both of which would top the US chart: Foreigner’s I Want To Know What Love Is and REO Speedwagon’s Can’t Fight This Feeling.

For AOR connoisseurs it was the best of times. There was, however, one great record from 1984 that had a sting in the tail: Journey singer Steve Perry’s solo album Street Talk.

Perry wasn’t the only member of Journey who was moonlighting that year; guitarist Neal Schon hooked up with his buddy Sammy Hagar in the brief-lived supergroup HSAS, while drummer Steve Smith busied himself with his jazz project Vital Information. But Perry’s record would have a huge impact on Journey’s career.

Street Talk was heavily influenced by the soul and R&B he had loved since he was a teenager, and after the album hit big – selling two million copies in the US alone – Perry steered Journey in a similar direction on the band’s subsequent album, Raised On Radio. As a result, Schon ended up sidelined in what had always been his band, and the definitive Journey line-up that made the classic albums Escape and Frontiers fractured with the exits of Smith and bassist Ross Valory.

But while Street Talk might have been a problem for Journey, it was a total triumph for the singer – as both a soft-rock masterpiece and a deeply personal statement. The album was written and recorded with a cast of famous and not-so-famous musicians, including guitarist Waddy Wachtel and drummer Craig Krampf, the latter from Perry’s pre-Journey band Alien Project.

At the absolute peak of his powers, for Street Talk Steve Perry put everything he had into a series of perfectly crafted songs: Oh Sherrie, written for his then partner Sherrie Swafford, became a massive hit single; Captured By The Moment, a beautiful eulogy for lost heroes such as Martin Luther King and soul legend singer Sam Cooke; Strung Out, a heartbreak song that rounded off the record in a hard-rocking fashion that Neal Schon might have found a little ironic.

In a year so full of amazing music, Steve Perry delivered one of the greatest AOR albums of all time.

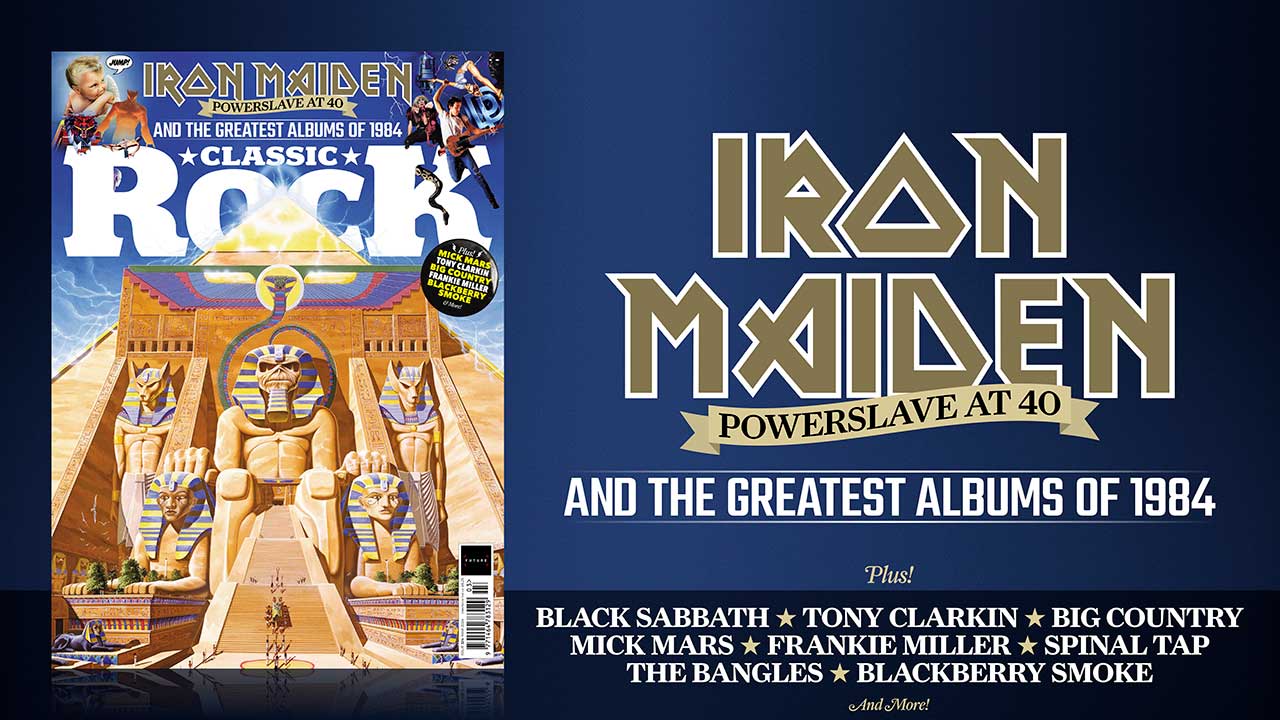

The brand new issue of Classic Rock is onsale now. Buy it online and have it delivered straight to your door