The cost of living crisis is deepening mental health problems for many people in the UK, with financial stresses rising rapidly just at the point when the pandemic, and the threat of isolation and lockdown, appeared to be subsiding.

Soaring inflation, coupled with uncertainty about jobs and income, is causing people to have to make “impossible choices” between heating and eating, and putting “huge pressure” on those with mental health problems, says Vicky Nash, head of policy and campaigns at Mind.

With prices rising far more quickly than incomes, and the looming threat of even higher energy and food bills to come, those who already suffer from anxiety are finding it hard to cope.

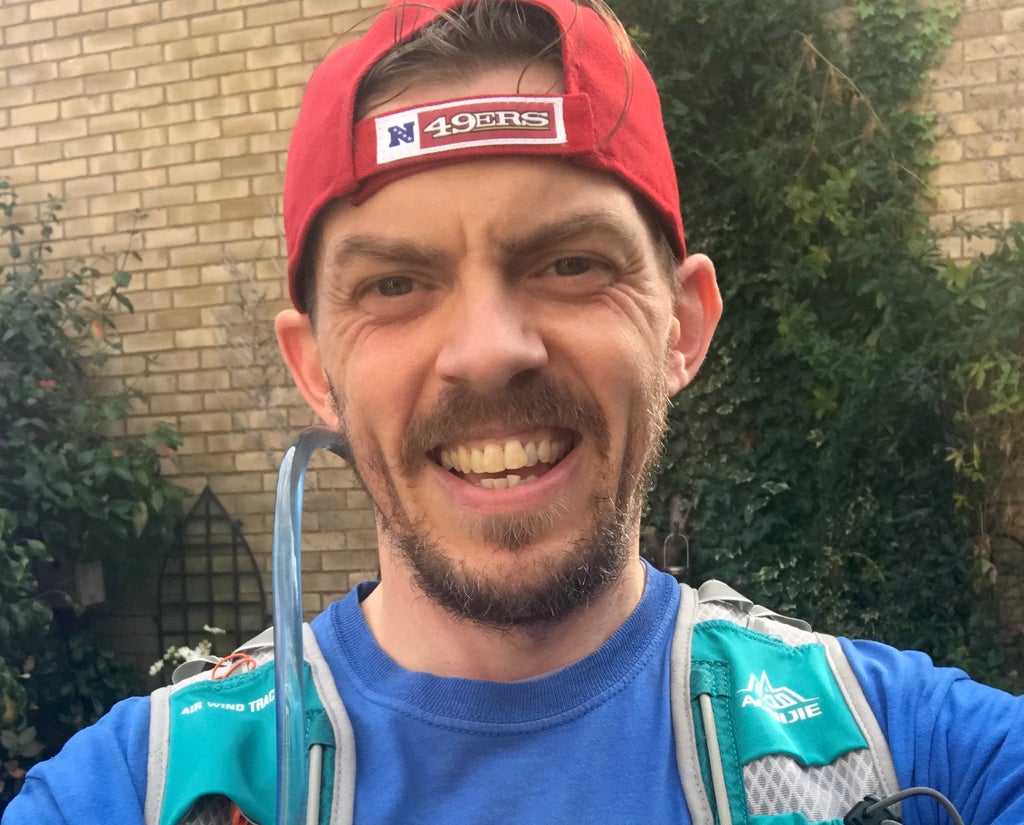

Paul Harris, 42, had a breakdown triggered by work-related stress five years ago, and had to leave his job in residential lettings. He suffers from anxiety and depression, which have been made worse by financial worries and debt. He has occasional work, giving talks and support to other sufferers, but has been unable to work full-time.

Income is “sporadic”, while rising bills are now a major source of anxiety, he says.

“I lose control quite quickly and my mood can drop rapidly to the point where I can’t do anything,” says Mr Harris. “We’re not in a destitute situation, but we are constantly worried about money.”

Mr Harris’s wife, who works in accounting, manages the household budget. The couple fell into debt after Mr Harris left work and they were forced to live on one income.

“Our credit rating is shot,” he says. “We can’t borrow any money, can’t get a mortgage. Buying a home seems like a very distant prospect. Because I’m not contributing financially, it really affects my self-worth and self-esteem. I feel a lot of pressure.”

That has been exacerbated significantly by huge increases to the couple’s household bills. Mr Harris says the couple are paying £100 a month more for energy, while his wife lost some clients during the pandemic.

“There can be something on the news about the energy bills going up, or we get a message from the utility company that can really, really bring me down very quickly,” he says, adding: “It definitely screws with an already vulnerable mind.”

Money and mental health are often linked, explains Ms Nash. “Poor mental health can make earning and managing money harder, and financial worries can have a huge impact on our mental health,” she says.

Benefits often provide a lifeline for people who are too unwell to work, or unable to find stable employment, but payments are going up at less than half the pace of inflation this year, delivering what amounts to a significant cut in income to recipients.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation estimates that the chancellor’s decision not to raise benefits in line with inflation will push 600,000 people into poverty.

Charities say the system is also needlessly complicated and stressful. Cases where people are wrongly denied payments, or are subjected to degrading and insensitive assessments, are frequent.

Mind says it regularly hears from people experiencing mental health problems who are left without money by the benefits system, which can cause someone’s mental health to worsen. Nearly half of those in receipt of benefits said their mental health was made much worse by their financial situation, according to Mind’s research.

Mr Harris has his own experience of this. He went in for an assessment in 2019, and was told by the Department for Work and Pensions that his personal independence payment (PIP) would be stopped.

“They told me that I was fine and that I didn’t qualify,” he says. “I knew that I wasn’t. They ask what progress you have made and say, ‘Well if you can do that, you can do it regularly,’ when you can’t. I was left financially worse off.” He has been fighting to have the payment reinstated ever since.

Ms Nash says she has seen numerous examples where people are asked to recount trauma or even suicide attempts. “This system too often prevents people from keeping afloat, or [leaves] people living in constant fear that their income will be suddenly cut off because of being sanctioned.”

A five-week delay before the first payment of universal credit is made often pushes people into debt, which can worsen their mental health.

Mind is also calling for an overhaul of Statutory Sick Pay (SSP), which is currently just £99.35 per week – one of the lowest rates of any wealthy country. Two-thirds of people with a mental health problem who received SSP said it had caused them financial problems, according to a poll by the charity.

“That puts more pressure on someone and reduces their chance of recovery,” says Ms Nash.

The link between financial problems and mental health works both ways, says Sue Anderson, head of media at debt charity StepChange.

“Being in debt can increase the risk of experiencing issues such as anxiety and depression, while people experiencing poor mental health may find it difficult to be in control of financial affairs, which can exacerbate debt problems,” she explains.

Ms Anderson advises taking steps to address the problem, such as calling StepChange’s advice line.

“Three months after taking debt advice, once people are beginning to make progress in dealing with their debt, their wellbeing on average shows noticeable improvement in terms of measures such as being able to sleep at night, and feeling better equipped to deal with day-to-day life,” she says.