It's been 15 years since the first 'review-bomb', when, in 2008, the anti-piracy protection applied to alien life-sim Spore saw it blasted by a wave of negative sentiment on Amazon. That coordinated backlash has set the tone for dozens, if not hundreds of similar efforts in the intervening decade and a half. Every protest draws from the same playbook, the backlash almost always centered around the same few points of contention: performance issues, unpopular business practices like paid mods or DRM; 'politics'.

Almost every review-bomb follows these same patterns – so why has it taken so long for some of the biggest review sites in the world to do anything about them?

Let's get Meta

There is obvious value in a coordinated user response to practices that don't benefit the player. In cases like the 2015 review-bomb of Skyrim – where players rallied against paid mods – what other recourse did the community have? The game had been out for four years. The option to 'vote with your wallet' simply didn't exist as it might have done for a brand-new game. There are multiple examples of players rightly making their feelings known to often faceless organizations, too. GTA 5 players rallied in defense of modding tools; Crusader Kings fans protested rising prices; Star Wars nuts turned on Battlefront II in their thousands after a disastrous launch plagued by loot boxes so prevalent they spawned anti-gambling legislation around the world.

But increasingly, the review-bomb is being used not as a tool to help the little guy stand up for himself, but as a means of protesting the way a creative team sees the world. That can be a financial viewpoint – ends of development cycles, exclusivity deals, and small-scale updates have all been bombed – or an emotional one; Horizon Forbidden West, The Last of Us 2, Superhot, and Death Stranding are just some high-profile games that saw audiences turn against them over narrative decisions.

Bombs Away

Recently, the publisher of one acclaimed JRPG pointed out that their game was being review-bombed. Micheal Hoss, of publisher Deck13, noted that a spate of negative reviews had appeared on the MetaCritic pages of Chained Echoes. Those negative reviews came months after a launch that netted the game a critics score of 90, but because they were just numbered 'ratings' rather than written reviews, they came with no reasoning attached.

Now it happened to us. @ChainedEchoes has been review bombed on Metacritic. Just plain ratings, no reviews. No reasons. We don't know why, it just happened. Didn't @metacritic want to stop this nonsense? Guess only for AAA games. #indiedev #metacritic #gamedev pic.twitter.com/Qit6pusT5FMay 9, 2023

He has no evidence to back up his ideas, but Hoss' assumption is that the review-bomb was in response to a decision to limit localisation on the game – referencing Spanish as an example, he cited a relatively small install-base against the significant cost of translating a 250,000-word story. As an indie publisher, that's not the kind of expense Deck13 can take on if it wants to bring more games like Chained Echoes to its audience, but in the face of the faceless, voiceless opposition of a MetaCritic user score, that doesn't matter.

Hoss has called on Metacritic to up its game. Speaking to GamesRadar+, he suggested the site could follow Steam's example, making users aware of massive swings of positive or negative reviews. It could increase its moderation efforts – something MetaCritic said it would do in the wake of Horizon Forbidden West's review-bomb. The site could check APIs to determine whether users actually own the game they're reviewing. All of these efforts might be more complex or costly to implement, but Hoss cites MetaCritic's size as evidence of its ability to absorb those costs.

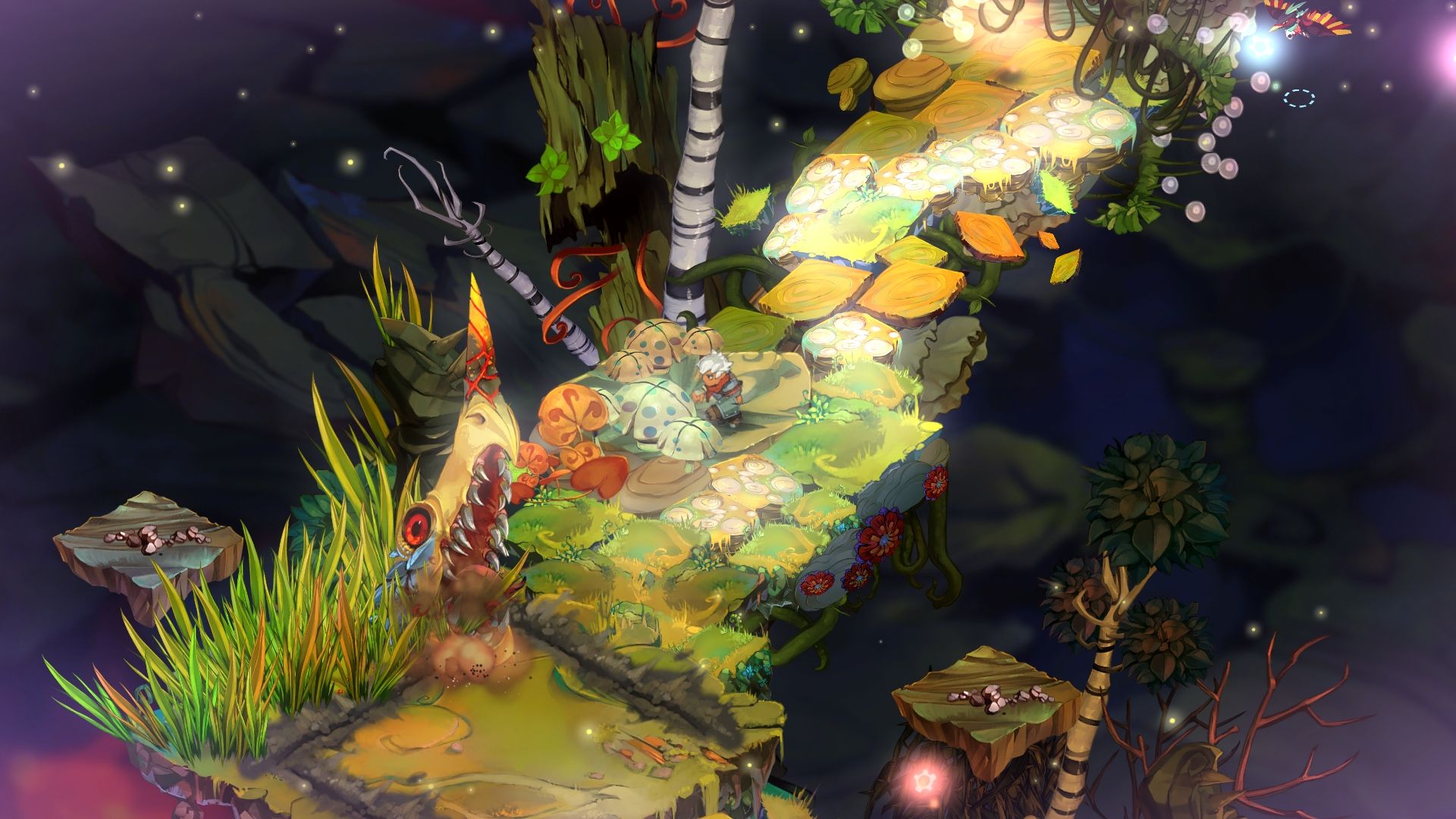

More important than its size, however, is MetaCritic's age. Review-bombing is no recent phenomena that the site is struggling to adjust to. Calls for greater oversight of user reviews on MetaCritic date back to 2011 and games like Bastion and Mass Effect 3. It took until Horizon Forbidden West's Burning Shores DLC – 12 years later – for MetaCritic to commit to "stricter moderation", but even its statement on that front is focused on user reviews that are reported for violating the site's policy on hate speech. It's not hard for a coordinated approach to duck around those barriers, especially if the protest isn't against inclusivity efforts.

Disappointing as any review-bomb might be, a major company can absorb the impact of a contingent of upset players. But Hoss points out that when this strategy is allowed to spread among massive games like The Last of Us, "a smaller indie can really suffer." When those games are more likely to feature the kind of inclusivity that sparks these backlashes in the first place, a perfect storm of abuse can form. "What starts on MetaCritic often leads to people harassing devs via social media or sending them hate mail. And MetaCritic bombings are often shared among certain communities and they gain traction and more ammo through that and pick up more people to send threats to developers."

The review-bomb isn't going to go away. Too many players know that there's a chance that they can force the change they want to see – or at least boost their own agendas – through a coordinated effort. They know that once a game is out there and the main glut of sales has been drawn in, the only thing a major company is likely to care about is a title's long-tail – the years of potential sales a game might make, which will be forever impacted by its review scores on platforms like Steam and Metacritic. But the sting needs to be taken out of the tail's strategy, to avoid exactly the kind of abuse that Hoss speaks of falling on the most vulnerable people in the games industry.

Horizon Forbidden West bore the most recent major review-bomb, facing criticism over the length and LGBT-content within its Burning Shores DLC.