When John Entwistle died in June 2002, we had to wonder: would we ever see another young hard-rock band produce a bass guitar hero with similarly radical techniques and tone – someone who could step forward in the music while still nailing the foundation?

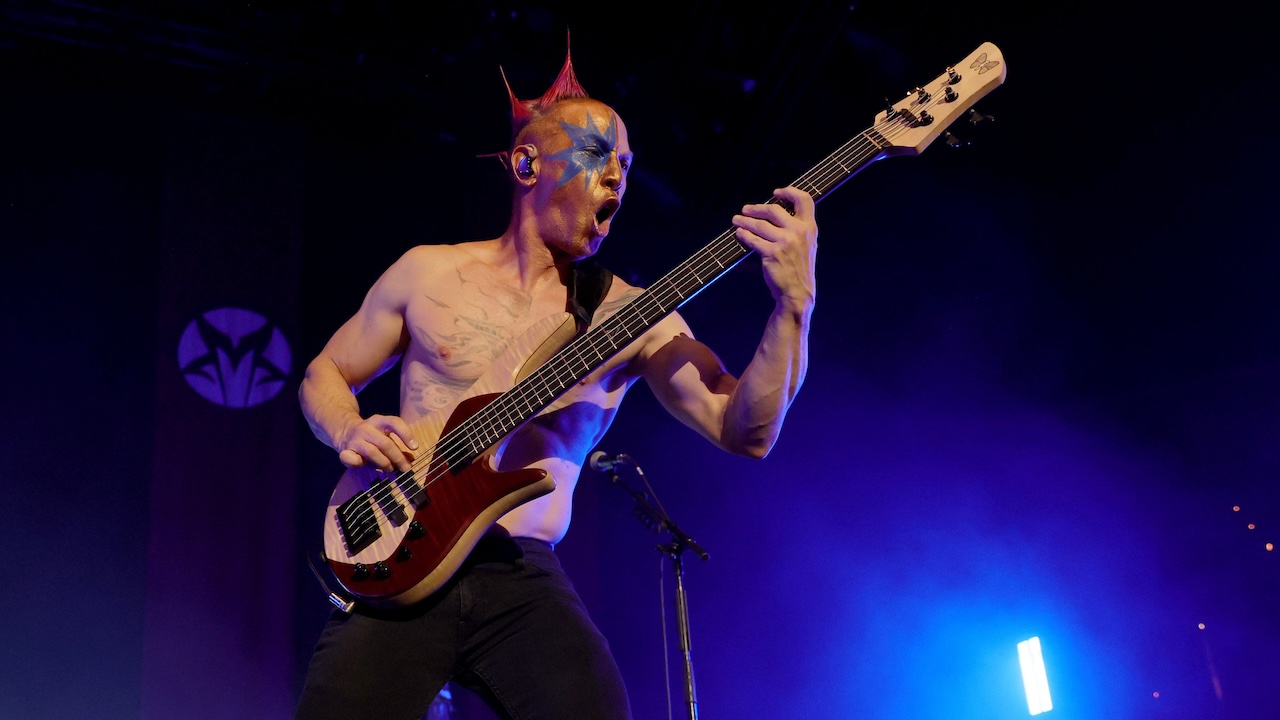

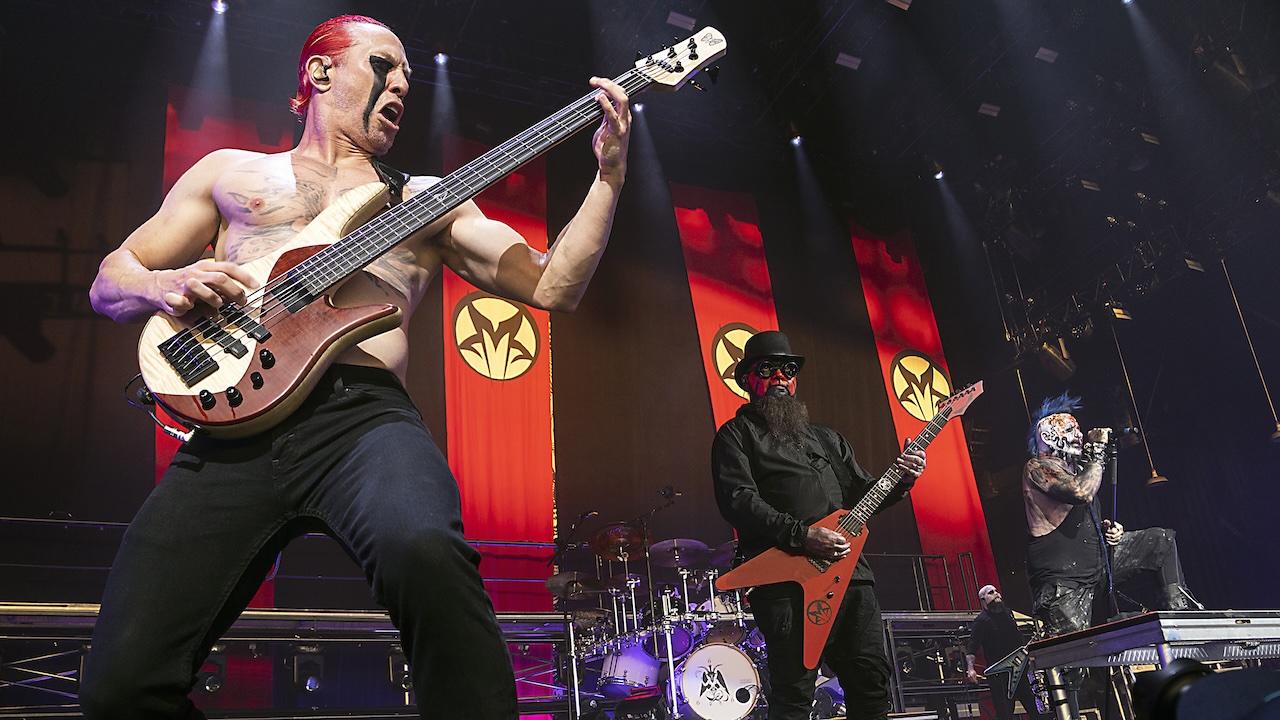

Check out Ryan Martinie, whose unique style separates him from the rest of the ‘nu-metal’ pack. On Mudvayne's gold-selling 2000 debut, L.D. 50, Martinie punctuated death-metal screams, polyrhythmic stop-and-start grooves, and odd-time chainsaw riffs with percussive slaps and taps, ringing double-and triple-stops, and melodic arpeggios.

Mudvayne's 2002 release, The End of All Things to Come, found the quartet embracing more of its melodic and non-metal influences, with Martinie exploring new methods to his madness.

Born in 1975 in Springfield, Illinois, Martinie was initially exposed to choral music and show tunes via activities at his family's church. His dad, who had a penchant for playing Jim Croce tunes on a nylon-string classical guitar, exposed him to the sounds of the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Doobie Brothers.

In the summer before 5th grade, Martinie discovered a cornet lying around, and began picking out melodies. He signed up for trumpet and choir in school and also began emulating his father's fingerstyle moves on the guitar. His folks noticed that he liked to pick out basslines on the guitar, so they bought him a Fender Squier P-Bass for his 12th birthday.

“Soon after, my parents separated and I had a lot of bitterness, so I started listening to angry rock and heavy metal,” Martinie told Bass Player. “The first three records I learned the basslines to were Iron Maiden's Caught Somewhere in Time, then Metallica's Kill 'Em All, and then Rush's Hemispheres.”

Martinie eventually landed in Broken Altar, a three-piece instrumental band playing “not very well-executed fusion and progressive-rock stuff.” The trio figured prominently in his burgeoning break-down-the-walls style, as he sought to match the motion, tone, and intensity of the drummer's double kick drum with his Ibanez Soundgear and Dean 5-strings.

Broken Altar opened a show for Mudvayne in 1995, and Martinie left an impression. Two years later, while working as a cook, he got a call to audition. “I think they were a bit unnerved when I first came in because I slapped and tapped. But they accepted the way I changed their sound, and they saw that I was playing for the songs, not showing off. I've never been about that.”

Back in January 2003 Martinie gave Bass Player a tour of Mudvayne’s second album, End of All Things to Come.

Bass-wise, how is the new album different from L.D. 50?

“Overall, we focused on melody and opened up more spaces for Chad to sing in. It's a warmer, more organic album that brings in more of our outside influences, as opposed to the cold, sterile, mechanical focus of L.D. 50. I still pulled out a few stops on bass, with some slapping, tapping, and chordal work, but my main concern was playing for the songs.”

At times you lock with the drums, and sometimes you double guitar lines, but often you function as a separate entity dancing between the two.

“I adhere to our music's rhythmic aspect, but I'm really drawn to the melodic elements. I often improvise between the main themes in our songs. For example, a lot of times instead of doubling the guitar note-for-note, I play a variation of the guitar line. The same is true with the drums; I always want to be locked in, but I'll play in between or around the different patterns.”

What's the origin of your unusual tuning?

“That's all Mudvayne. When I joined the band, I tuned my 5-string F# B F# B E. We used that tuning on L.D. 50, but we had intonation problems.”

“For this album we came up a half-step; I used mainly my Warwick 4-string, tuned C G C F. The move up was mainly because Chad felt more comfortable singing there, but it also helped with the intonation.”

On Silenced and The Patient Mental, what technique do you use to double the intricate guitar lines?

“I used fingerstyle plucking with my thumb, index, middle, and ring fingers, which comes from playing my dad's classical guitar growing up. Sometimes I use my pinkie, too. The opening riff on Mental was especially tricky and spider-like.”

“One thing I explored on this album was utilizing the lower strings on the upper part of the neck, which I do on that opening riff. It gives those notes a warmth and roundness you don't get when you play them closer to the headstock.

“In the verse's second part I move from the bottom of the neck to the top to nail a double-stop, which is something else I've been doing more of lately – you can also hear it on Mercy, Severity and Solve et Coagula.”

In the opening sections of Trapped in the Wake of a Dream and (Per) Version of the Truth you play notes that sound like slaps.

“Those are what I call downward plucks or taps. I strike the strings with my fingertips using a downward wrist flick. It's sort of like what Geezer Butler or John Entwistle did, but Entwistle held his arm parallel to the strings. My arm is more in the traditional plucking position.

“I strike the strings both over the neck – where the tone is a bit thinner and you have to be aware of overtones – and between the end of the neck and front pickup, which I do more often because it sounds punchier. Basically, I use the string like a trampoline, taking advantage of the natural bounce and the give-and-take of energy – almost like hitting a snare drum.”

How did you develop that technique?

“I started doing it around the time I joined Broken Altar; back then I was constantly trying to step outside the box and develop new techniques. That band was key in the development of my style, especially my right-hand stuff. The drummer played with a double kick drum, which was a first for me, and hearing that helicopter-like rumble was a turning point tone-wise and rhythmically.

“I wanted to emulate both the deep thud and high-end click of a kick drum and be able to do it in succession, so I could keep up with the drummer's foot. I also wanted to match the percussive sound of jazz upright bassists I had heard.”

Do the odd-time figures in Trapped in the Wake of a Dream correspond to Mudvayne's ‘math metal’ method of writing?

“It does, but we don't want to give away all the secrets! We’ve been holding off because we kind of hope fans will figure it out. I can say that this whole song was built from a number sequence and that it's basically in 11/8.”

“For us, ‘math metal’ refers to exploring a series of numbers, but it can also be something that's happened upon, where you realize there are number patterns in a song that occurred naturally and you continue that path.”

The first single, Not Falling, incorporates many of the band's trademarks.

“As well as our new direction. This and the next track, (Per) Version of the Truth, were the first two songs we wrote, so they're kind of musically married to each other. Falling has the heavy stuff, but it also has the big, melodic spaces.

“For the opening riff, I combined both downward plucks and back-and-forth strums with my hand bunched up as if I'm holding a pick, using my index fingernail as the striking point. In the softer, melodic bridge I just improvised a finger-plucked bassline off the chord changes, and you can hear us flipping the beat over at times. We do that a lot.”

World So Cold is even more of a melodic departure.

“That's my favorite song on the album, much the way Severed was on L.D. 50. Since I'm so drawn to melody, the band's melody-driven songs are the most fulfilling for me. Personally, I got to explore new melodic terrain with my moving verse bassline and fills on World So Cold.”

Skrying is considerably heavier, but it still has melodic moments.

“After the bass breakdown, which was inspired by the weird guitar line, we bust out and reach one of the album's climactic centrepieces. One of the techniques I use in the opening and closing sections is octave double-stops played low on the neck, using downward plucks with my index and middle fingers.

“Because of our tuning, the octaves fall in the same fret on the bottom and 3rd strings, so I can play a D octave at the 2nd fret. Sometimes I stretch my pinkie over to the top string's 4th fret to reach the A so I can get the 5th in there, too.”

The opening and verses of Shadow of a Man have interesting motion between the bass and guitar.

“We like the idea of the bass and guitar playing ascending and descending lines against each other to create a sort of counterpoint. At the same time the part has a reggae-ish funk flavor that strays a bit from the drums to create this weird pocket that everything sits in. I used my fingers for that; then the cascading line in the chorus is all back-and-forth strumming.”

The End of All Things to Come has the album's only slapping.

“That song is our show opener. It's a fairly simple, full-on heavy metal track in the traditional sense. At the top I'm doing downward plucks, but in the next section it's straight-up slapping. I was afraid it was going to be too reminiscent of Dig from L.D. 50, and that I'd be repeating myself creatively, but it just worked. It needed that punchy fusion-esque element; it makes for a cool contrast.”

How do you play the cool slides in the verses of A Key to Nothing?

“I used my fretless Pedulla Buzz 4-string. The rest of the song is my Warwick Thumb 4, but the verses had this strange juxtaposition with the guitar sitting front-and-center as the fulcrum, and the bass and drums on either side teetering back and forth. So I felt it needed some kind of greasy, dirty, slightly off vibe. It's sloppy and out of tune at times, but it seems to benefit the track.”