Diversity, inclusion and equity policies are now broadly endorsed in Australian organisations. But not all diversities are equal. Our research suggests while programs for women and some racial minorities are being embraced, other diversities are excluded.

In particular social class is ignored, and people with invisible, subtle or complex diversities are seldom considered.

The almost exclusive and independent focus on gender and race is not surprising, given Australia’s history. Colonisation and the dispossession of Indigenous Australians, the legacy of the White Australia Policy and persistent discrimination against women at work are all realities with which, as a nation, we have not fully reconciled with.

But if everyone in Australia is going to get a fair go at work, all the disadvantages people face need to be recognised.

What our research involved

Our research project involved three Australian organisations over four years. One was the Australian subsidiary of a global technology business, another a national sports organisation, and the third a state government agency.

These organisations were selected because they operated in different sectors yet were known for their best-practice approach to diversity and inclusion. We spent up to nine months in each organisation, giving us enough time to learn about their cultures and see how initiatives and ideas played out. The agreement was that we would keep their identities anonymous in exchange for such access and freedom to report our findings, even if unflattering.

There was much to be impressed by. The chief executives supported equality in the workplace, diversity was seen as fundamental to developing the business, there was investment in diversity initiatives, and employees knew where their organisations stood.

Hierarchies of diversity

But we also found that how senior leaders managed diversity and inclusion created unintended consequences. Each organisation had a “hierarchy of diversity” – in terms of what, and who, got attention.

What stood out in all three organisations was that when women, or men from a culturally diverse minority, were in senior positions they still almost always came from a similar socio-economic background as other executives.

Though the term is not often used today in what many assume to be a socially mobile Australia, they shared what used to be commonly called “class” attributes. Almost exclusively, those in positions of power had similar experiences and interests borne from having been educated in an elite university and living in affluent suburbs.

This was apparent to staff who commented on how leaders tended to be involved in similar weekend activities and spent time in the same places (including restaurants) outside of work hours.

If they were women in senior leadership positions there was an expectation they would “play the game”, behaving in ways consistent with the “White male” executive norm. Coming from at least an “upper middle class” background made this much easier for them.

This reality, based on social and socio-economic privilege, was something barely talked about. But the lack of diversity on this dimension was palpable.

Acknowledging ‘intersectionality’

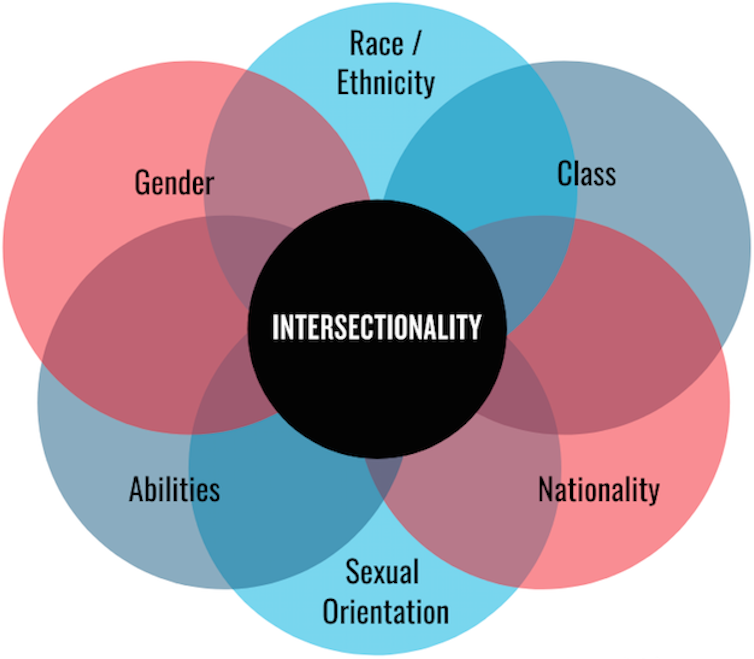

That some forms of systemic exclusion or discrimination are recognised and addressed while others remain largely invisible has been explored through the concept of “intersectionality”, which draws attention to how different forms of diversity and disadvantage intersect, creating unacknowledged forms of discrimination.

The term was first used in 1989 by American legal scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, and stemmed from her work developing critical race theory and the lived experienced of poor African-American women in the US, who have face discrimination different to that by white women or black men.

We saw this reality in our research.

The director of one of the organisations we studied, and the only Indigenous woman in a leadership position, told us:

I get often treated by some managers and executives like I’m not really on the executive. I don’t get treated with the same respect as my peers by some of them. […] Partly it’s obviously because I’m black, partly it’s I’m a woman.

Having observed this organisation over a lengthy period, we can attest that her perceptions are legitimate. There may be no “conscious” bias involved, but it is fair to conclude that a female executive who wasn’t Indigenous would have a different experience.

Even though these organisations didn’t acknowledge intersectionality in their policies and practice, employees were certainly aware of it. One person we spoke to cited the case of a senior manager, a woman born in India:

She’s a smart woman from an Indian background and she’s always being treated like the last wheel.

In another case, one of the people we spoke to talked about two of his Indian colleagues:

You couldn’t bottle them both up and say ‘they’re both Indians’, because they’re completely different. One’s from a rich background and one’s from a poorer background. They’ve got different mentalities and different ambitions. They’re different workers and different people.

Read more: What is intersectionality? All of who I am

Diversifying diversity

Diversity and inclusion polices and programs are contributing to progress in reducing entrenched forms of discrimination and disadvantage in the workplace. But if these programs are to truly benefit our most disadvantaged groups, such as Indigenous people who come from low socio-economic backgrounds, much more will have to be done.

The way we understand diversity needs to be diversified. If we continue to privilege gender and race as if they are the only ways by which people are treated differently and excluded from leadership, many inequalities will remain.

Read more: Six misunderstood concepts about diversity in the workplace and why they matter

Our research highlighted the intersectionality of race, gender and class as significant oversights in how we manage diversity. But there are many other intersections to consider – including the treatment of those with different sexual and gender identities, and people with different physical and neurodivergent abilities.

It’s up to all of us to challenge ourselves to understand how we privilege some differences over others. Reducing complex differences to a limited number of simple measurable categories blinds organisations to how privilege and discrimination operate at work.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.