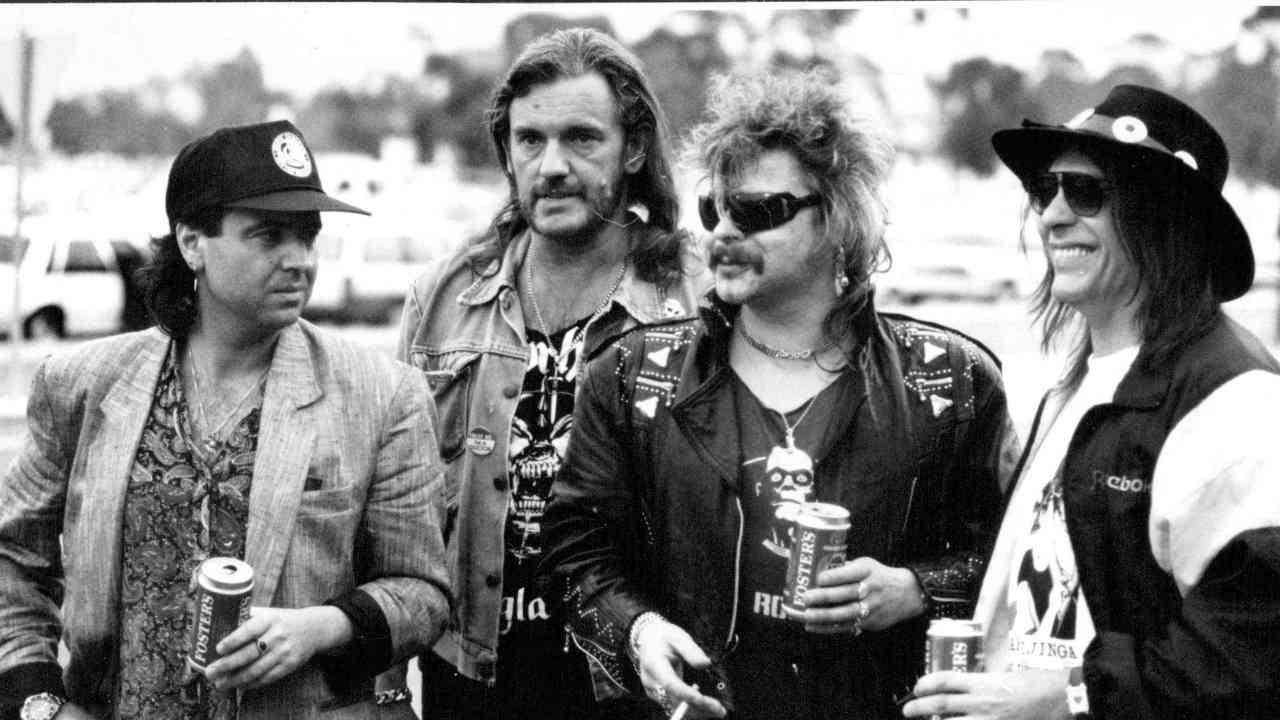

In the spring of 1984, Motörhead had yet another new line-up. Just a few weeks after guitarists Phil Campbell and Würzel had been installed, drummer Philthy Animal Taylor quit and was replaced by Pete Gill, formerly of Saxon. But the new-look quartet gelled quickly. In a Bronze Records press release, Campbell commented on joining the band with the immortal words: “It’s good to be back on the folk circuit.” Meanwhile, Würzel revealed that he had agreed to jump on board “because Motörhead are my granny’s favourite band”.

“That’s all I need at my age – to be in a band with the Bash Street Kids,” quipped Lemmy, who was on the verge of turning 40 at the time.

The bassist/vocalist had, nevertheless, already invested almost a decade of his life in Motörhead, who announced a pair of 10th-anniversary gigs to introduce the Kilmister-Campbell-Würzel-Gill line-up at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in late June, with special guests Wendy O Williams and Rogue Male.

The shows – which featured a naked lady bursting out of a cake, and a jam with former ’Head boys Fast Eddie Clarke, Philthy Animal Taylor, Lucas Fox, Larry Wallis and Brian Robertson – put the band back on the map in no uncertain terms.

Such was the camaraderie within the new line-up that they all moved into a house together. It’s unknown whether next door’s lawn died, though they did invite Record Mirror to conduct a Through The Keyhole-style interview. Phil Campbell was absent on the day, but it was reported that Pete Gill had an impressive scrapbook collection, that Würzel liked model engines and train spotting, and that Lemmy’s room was full to the ceiling with books.

In September ’84 Phil Campbell and Würzel made their debut on record with the band on the double-disc compilation album No Remorse, which included the quasi-legendary Killed By Death. And the news got better still. In early 1986 the band settled out of court to end a year-long legal battle with the seemingly doomed Bronze Records, their management opting instead to set up GWR Records as a home for the ’Head and long-time buddies Girlschool.

No sooner had the ink dried on the deal than it was announced that work would begin on a follow-up to the two-and-half-year-old Another Perfect Day with producer Tony Taverner. “We’re back,” Lemmy growled. “And any fucker who thought we were dead had better head for Tibet cos that’s the only place which is gonna be safe from this band.”

In fact, Taverner was replaced by Bill Laswell for the band’s seventh studio album, which had a working title of Riding With The Driver. At the last minute they switched it to Orgasmatron, but it was too late to change Joe Petagno’s cover art.

Orgasmatron was released in mid-1986 and, in contrast to the mixed reaction to Another Perfect Day, gained widespread acclaim. Orgasmatron contained some of the band’s heaviest songs to date, including Deaf Forever, Doctor Rock, Nothing Up My Sleeve and the ominous, pummelling title track, later covered by Brazilian metalheads Sepultura.

On August 16, 1986 Motörhead appeared at the Monsters Of Rock festival at Donington Park, the UK’s premier hard rock and heavy metal event. The bill was headlined by Lemmy’s old friend Ozzy Osbourne, the line-up completed by Scorpions, Def Leppard, comedy troupe Bad News and Warlock.

It was rumoured that Motörhead would fly in to Donington Park aboard two World War II Messerschmitt bombers, but Lemmy pooh-poohed this. “That’s a stupid rumour put about by counter-revolutionary elements to undermine the state,” he said. But the band certainly made a big impression. Their set was electrifying, from the opening battery of Iron Fist to a bulldozing Overkill. And when a lit flare was thrown from the audience on to the stage, Lemmy halted the show to berate the idiot who’d thrown it. He then challenged them to come on stage to take their punishment. But nobody was fool enough to do that.

Addressing the situation some years later, Lemmy pondered: “What I wanna know is, what is wrong with these audiences? What makes them want to throw things on stage? Why do they think that violence is a good deal? These kids have something in their heads that I just don’t get at all.”

In the spring of 1987, Philthy Animal Taylor made a surprise return to the band. “Pete Gill just got fed up and left, and who better to come in than Phil?” explained Würzel.

Gill would attribute his exit to “purely business reasons, nothing whatever to do with musical or personal differences”.

Taylor, who had tried to form a band with Brian Robertson and former Michael Schenker Group bass player Chris Glen, was thrilled to be back in Motörhead. “I always regretted leaving,” Taylor said. “Let’s just say I took a three-year holiday. If you thought that Motörhead were out of control in the past then you ain’t seen nothing yet.”

The new-look Motörhead threw themselves into their next project, a film called Eat The Rich, recording six songs for its soundtrack (the album of which also included Würzel’s solo single Bess). With a script written by the team responsible for the successful Comic Strip series, it starred Ronnie Allen (best known for his role as David Hunter in the soap opera Crossroads), Kathy Burke, Robbie Coltrane, glamour model Fiona Richmond, and Lemmy as a character called Spider.

The song Eat The Rich eventually featured on the band’s eighth album, Rock ’N’ Roll, in September ’87, the sleeve of which bore the legend: “Welcome home Philthy!”

Rock ’N’ Roll included the classic tracks Rock ’N’ Roll, Stone Deaf In The USA and Traitor. It also featured a cameo from Monty Python star Michael Palin, who recited a prayer at the end of Stone Deaf In The USA. “It was great to meet a hero who didn’t turn out to be a cunt,” summarised Lemmy graciously.

On a more serious note, Rock ’N’ Roll was also self-produced, albeit in conjunction with Guy Bidmead. “I wasn’t totally happy with what Bill Laswell did on Orgasmatron, though he was going in the right direction,” explained Lemmy.

Bidmead remained as a co-producer for the next album, a concert release titled Nö Sleep At All, recorded at a festival in Hämeenlinna, Finland and released at the arse end of 1988.

With their next studio album still a hefty three years away, Motörhead settled down to a serious bout of touring that took them to all four corners of the globe. Frustratingly, they also contested a protracted legal battle with GWR Records, signing a new deal with the Epic subsidiary WTG in mid-1990. Out on the road, Lemmy was hospitalised after being struck on the hand by a sharp object thrown by a member of a Yugoslavian crowd. Despite being in severe pain he completed the show. Afterwards he had seven stitches in the wound.

As the WTG deal became a reality and the seeds for the album that would become known as 1916 were sown, the band moved their organisation to Los Angeles, with Lemmy and Philthy Animal opting to relocate there. This switch was greeted with some scepticism. Amid their ‘Lemmy Goes To Hollywood’ headlines, the UK press worked themselves into a frenzy with all sorts of ‘Motörhead seek Yankee dollar’ theories. “The move to Los Angeles,” stated Lemmy, “is so that we can attempt to make an impact on the American market. It’s much easier if we are based there.”

“We’re certainly not going to turn our backs on England,” added Philthy. “We’re still going to tour here once a year.”

WTG’s cash would open up a whole new world to Motörhead. “When they said ‘pre-production’, we replied, ‘Oh, you mean like rehearsal time?’” grinned Philthy. “They said, ‘No, no, no, guys… pre-pro-duc-tion.’ And it was like, ‘Oh, we’ve never done that before.’”

“The speed the other albums were done at, there was never any time for overdubs or to listen to the mixes and change them if we wanted to,” Würzel said. “We always had to keep an eye on getting out of the studio.”

During the making of 1916, Philthy stated: “It’ll be the best Motörhead album since Ace Of Spades. Just because Lemmy and me are going to live in the States, there’s no way we are going to start sounding like Bon Jovi or anything.”

These words made sense, of course. But, to their horror, the band realised the album would take much longer than anyone had suspected. As a result, Motörhead were forced to postpone a UK tour in December 1990.

“We haven’t had any time to rehearse a live show and Motörhead don’t believe in giving below-par performances,” Lemmy apologised. “It’s better that we wait till the new year and give our fans not only our best LP ever, but our best ever tour as well.”

The album was delayed in part by a change of producer mid-way through. Originally, Dave Edmunds of the Welsh rock’n’roll band Rockpile had been considered for the job of producing the record. Instead the job went to Ed Stasium, producer of the Ramones and Living Colour, among others. However, after various disagreements with the band, Stasium was fired and the album was completed with another producer, Pete Solley.

The album finally arrived in January 1991 – a whopping four years after Rock ’N’ Roll. But it was worth the wait. The highlight was its title track, a ballad about the realities of the First World War’s Battle of the Somme, that boasts some of Lemmy’s all-time best lyrics: ‘I heard my friend cry, and he sank to his knees/Coughing blood as he screamed for his mother/And I fell by his side, and that’s how we died.’

And so it came to pass that in 1991, a new, more competitive Motörhead gazed out on the world. 1916 was a huge success, bringing the band increased sales and renewed critical and artistic kudos, even a stab at winning a prestigious Grammy award (though the band eventually lost out to their friends Metallica and their Black Album).

“I don’t give a damn what people say,” commented Lemmy, by now bored to the back teeth with the sell-out accusations. “Why should I stay in England? I lived there for almost 44 years and almost starved as a musician. I hadn’t been in the States for two years before we got our first Grammy nomination.” ’Nuff said.

Though the arrangement helped to get Motörhead back on track, the group never felt too comfortable on a major label. Lemmy later related the tale of how, even after the Grammy nomination, he was snubbed by the company’s boss. “I went to New York for the Grammy party and Tommy Mottola, the head of Epic at the time, wouldn’t come out and see me,” he said. “He never even said hi.”

For a brief period, the band were managed by Phil Carson, former chief executive for Atlantic Records, who had worked with such legendary rock acts as Led Zeppelin and AC/DC. Then they signed up with Sharon Osbourne, and her robust style was just what they needed. “Sharon took guys on at their own game – they would run screaming from the room,” Lemmy laughed. “In full flow she’s quite a sight to see. Put it this way: I’m glad she likes me.”

After parting with Osbourne, they then hooked up with Todd Singerman, who still handles the band’s affairs today.

Pete Solley remained in charge of producing 1992’s March Ör Die, the band’s final album to feature Philthy, who quit after playing on one song from that record. In fact, most of the tracks on the finished album would feature the much-travelled Tommy Aldridge, whose career included stints with Black Oak Arkansas and Whitesnake.

Following Philthy’s exit, former Don Dokken/King Diamond drummer Mikkey Dee was classed at first as a temporary stand-in, but joined permanently when the offer came. And the arrival of Dee, who Lemmy calls “the greatest drummer in the world” during every Motörhead live show, introduced another livewire personality to the band.

March Ör Die featured two high-profile guests too: Guns N’ Roses guitarist Slash, who actually rang the band and requested to join in on a couple of tracks, and Ozzy Osbourne, who duetted with Lemmy on I Ain’t No Nice Guy.

Given the Tommy Mottola incident, it may come as no surprise to learn that March Ör Die was Motörhead’s final album for WTG. Lemmy, who later claimed that it would have been a hit had the label distributed it properly, was willing to join the dots: “Maybe they thought they were getting the so-called Grandfathers Of Thrash, and of course they weren’t. They were signing an opinionated older guy and three younger geezers who were even worse.”

With the rock music scene obsessed with grunge music, 1993 was a strange year for Motörhead. The band’s provocatively titled album Bastards was a back-to-basics rock’n’roll record that was partly a reaction to the more sophisticated approach employed on 1916 and March Ör Die. As Würzel explained: “We made a conscious attempt to kick more ass.”

The first of four Motörhead albums to be produced by Howard Benson, Bastards featured some of band’s fiercest music till that point. And on a more cerebral level, the lyrics to Don’t Let Daddy Kiss Me, which condemned child abuse, were both angry and poignant.

Lemmy acknowledged Motörhead’s outsider status. “It’s been a blessing to have been underdogs for so long,” he mused. “It’s kept us hungry. I’m bloody ravenous because I hate injustice and I love my band.”

And while Motörhead had recently signed to the German-based independent imprint ZYX Music, Lemmy was still reeling from the “injustice” of Motörhead’s treatment by Epic Records.

“To them we were just a tax loss, even when we gave them a hit,” he seethed. “We picked up 82 AOR radio stations with a track that featured both Ozzy and Slash [I Ain’t No Nice Guy] and they wouldn’t even pay for us to make a video. We made one for eight grand of our own money and still they wouldn’t push it.”

For all his anger, Lemmy remained unchanged. “I still believe in rock’n’roll,” he thundered. “I’m bitter and twisted, but strangely optimistic and full of fluffy gentleness – like a little bunny.”

Things were looking up when Sacrifice, the band’s 12th studio album, dropped in the summer of 1995 via SPV/Steamhammer, another German-based company, but one with more of a hard-rock pedigree than ZYX Music. But the band were noticing some problems with Würzel, who would quit the group upon completion of the album. That said, Sacrifice is an album that continues to sit well with Lemmy. In his sleeve notes he jokes: “Put it in your system and your girlfriend’s clothes fall off.”

Phil Campbell, who would embrace the opportunity to become Motörhead’s sole lead guitarist, had forged a strong bond with Würzel after many years of touring and recording, and still rues the day the former army corporal informed the band that he was leaving.

“Würz was great, really up for it at the start. He was always laughing and joking. That lasted for quite a few years, but towards the end he wasn’t quite so interested.”

Though the departure was acrimonious at the time, once tempers died down Würzel retained contact with Motörhead and jammed with them on occasions, before his tragic death in July 2011.

For Lemmy, Campbell and Dee, in the summer of 1995 there were still records to be made, concerts to be played, eardrums to be deafened and women to chase. And that’s exactly what they did.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Motörhead