Both as a musician and in-demand studio engineer, Rafael Anton Irisarri has always drawn on a wide range of influences. His debut album as The Sight Below, released on Ghostly International in the late ‘00s, was a work of ambient techno that was clearly influenced by the likes of GAS and Dettinger, but also aligned with the grungy guitars of shoegaze.

“I’m a self-taught musician who grew up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, learning guitar and bass by playing along to records,” Irisarri tells us. “Coming from a working-class family, most of my music came from hand-me-downs, starting with heavy metal cassettes in my early years. My musical horizons expanded when my uncle introduced me to reggae and dub music, and at 15, a friend from the industrial scene introduced me to ambient music via The Orb. Afterwards, I explored everything from The Cure, Joy Division, and Kraftwerk to My Bloody Valentine, Cocteau Twins, Harold Budd, Talk Talk, and Slowdive.”

In the 2000s, Irisarri moved to Seattle, becoming involved in the city’s electronic music scene and increasingly finding himself running front of house sound at shows. Experience working behind FOH consoles led to an interest in studio technology, and Irisarri began to hone his engineering skills polishing up recordings for friends and studying the craft of mixing and mastering. This experience eventually led to the founding of his own studio in the late ‘00s.

“It was a dark, hillside room with little sunlight, so we named it Black Knoll,” he explains. Since its inception, Black Knoll has played a role in mixing and mastering releases from a diverse array of artists including the likes of Julie Byrne, Hana Vu, Telefon Tel Aviv, Galcher Lustwerk, Emeralds’ Steve Hauschildt, Lusine, and more.

In 2014, during the process of relocating to New York, Irissari was robbed of his studio gear and all of his possessions. “It was a devastating and incredibly stressful time, to say the least,” he explains. “Thanks to the kindness of strangers, friends, and listeners – and the incredible support of the Ghostly International family – I was able to rebuild the studio in 2015. After the rebuild, the studio client base grew significantly, working with so many great labels like Temporary Residence, Dead Oceans, Felte, and of course Ghostly, to name a few. Over the last few years I’ve found myself working with more genre-spanning independent artists, podcasts, and art house film projects from all over the world.”

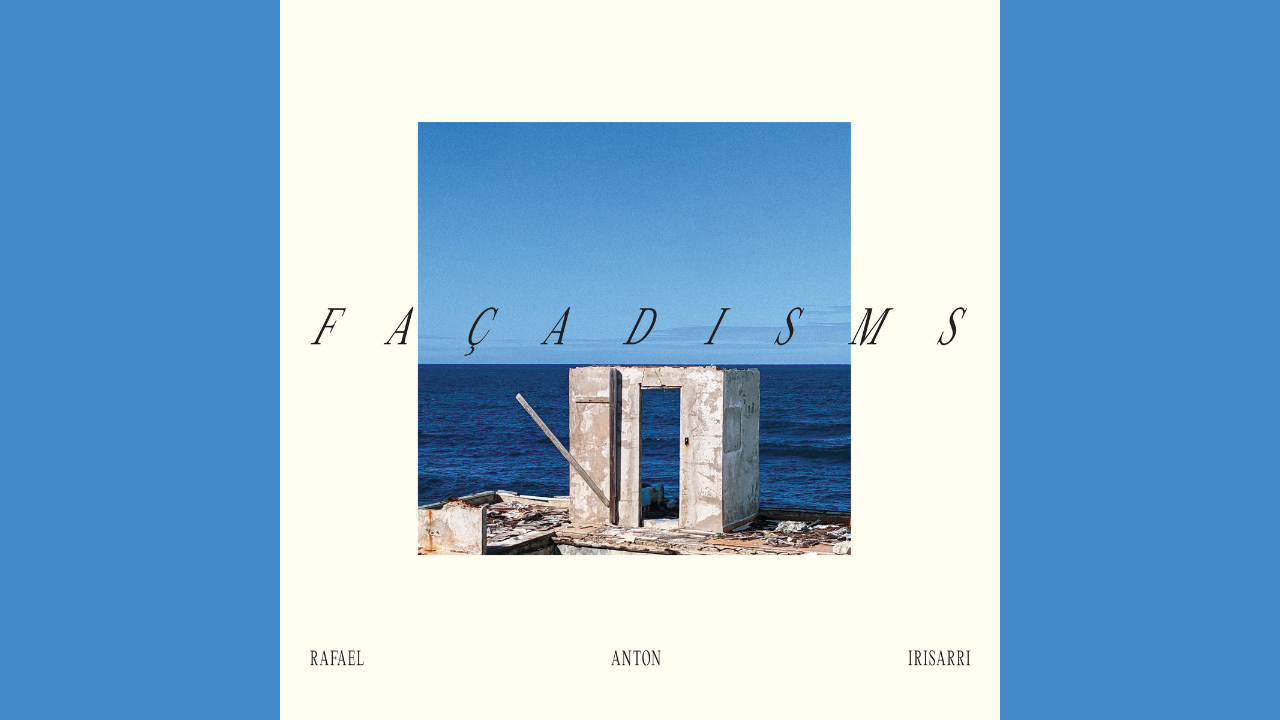

This autumn sees Irissari release his latest album, FAÇADISMS, under his own name. Inspired by brutalist architecture and incorporating collaborations with artists including KMRU, Hannah Elizabeth Cox and cellist Julia Kent, the album is a rich work of textural drones, evolving atmospheric guitars and layer effects. We spoke to Irisarri to find out more about his approach to mixing and mastering and the creation of FAÇADISMS.

How do you define your personal approach to mixing/mastering?

“I view mastering as a system of checks and balances. My aim as a mastering engineer is to listen and align myself to what the essence of the music is and to preserve that, while enriching the sound to make the album the best version of the artist’s vision. My approach is rooted in respect; for the artists, the aesthetics I believe in, as well as the craft itself.

“For me, it’s crucial to align with the music I’m working on. I’m highly selective and I only work on music that I genuinely enjoy because it’s impossible to do a great job if you don’t truly connect with what you’re hearing. I also need to resonate with the artist’s vision and aesthetics; something magical happens when our creative values align. Although mastering is primarily a technical trade, there have been many times when my own production sensibilities have contributed to enhancing a recording.”

Talk us through the key elements of your studio. Are there any tools you use time-and-time-again for mixing or mastering?

“My primary focus is mastering, but I occasionally take on mixing projects or invite mixing engineers to use my studio. For example, the last few years I’ve mixed for the pioneering Japanese band MONO on their annual _Heaven_ series.

“At the heart of my studio is the Maselec MTC-1X console, which serves as my monitoring path and master transfer console, connecting all my mastering hardware and AD/DA converters and speakers. It offers excellent functionality for auditioning and A/Bing tracks.

“I operate a hybrid setup, blending digital precision with analogue warmth, and rely on key tools that have become staples in my workflow. For EQing, I’m particularly fond of the Curve Bender and the Sontec 250. The Sontec has become indispensable – I use it on almost everything because you simply can’t go wrong with it! Compression is another critical component of my setup. I often reach for my customised Foote P3S ME, which offers incredible transparency and control, and the Gyraf Audio G24, which I consider my ‘secret weapon’. At the end of my mastering chain, I use a VariMu – it’s the glue that binds everything together and gives the master a cohesive feel.

“For mixing, I lean on my Obsidian bus compressor, which is patched to the master bus insert of my Neve summing mixer. It’s my go-to for adding punch across a mix. When it comes to processing drums and vocals, I often use the Carnaby EQs. The harmonics they add are simply fantastic, bringing out richness and depth in both the drum and vocal buses. The TG-2 preamps are also a favourite for saturating stems, adding warmth and grit that give tracks that extra bit of ‘mojo.’

“Everything finally comes together in ProTools, which allows me to seamlessly blend all the analogue and digital processing into the final mix or master.”

You’ve worked on a lot of music that touches on ambient, experimental and ‘post-rock’, where dynamics play a very different role to, say, a radio-friendly pop track. Do you have any specific techniques for preserving that balance?

“For me, the most crucial thing is to understand the intention behind the music and the aesthetics. Ambient music, for instance, is a deceptively simple and minimal style of music that relies heavily on subtle, delicate movements. When working with ambient, classical, experimental, and post-rock music, preserving dynamics is crucial, as they play a key role in the emotional impact and atmosphere of the recording.

“Unlike radio-friendly pop, where loudness is often prioritised, these genres require a nuanced approach to maintain their depth and subtlety. In post-rock, for example, quiet moments can be just as powerful as the loud ones. I focus on gentle, transparent compression, using tools that help control peaks without squashing the life out of the music. I monitor levels closely, ensuring the quieter sections retain their impact and that crescendos still have room to expand.

Artists seek my understanding of specific genres and cultures that aren’t always handled well by more mainstream mastering houses

“The goal is to enhance the music without compromising its emotional arc, which often comes from its dynamic shifts. When it comes to EQ, I’m careful not to overdo it. For example, in ambient music, where textures and timbres are often the focal points, it’s important to maintain the tonal balance without altering the original character of the sounds. I’ll use EQs to subtly shape the frequency spectrum while preserving the integrity of the original recordings.

“Overall, my methods are all about balance and subtlety. The techniques I use are aimed at enhancing the natural dynamics of the music rather than forcing it into a loudness-driven mould. It’s a process of careful listening and restraint, making sure that the final product really stays true to the artist’s intention.”

When you’re working with other artists, how closely do you work with them on a mixdown or mastering session?

“It’s absolutely essential to involve the artist in the process, especially when mixing. I wouldn’t even consider mixing a song without the artist’s input because mixing is a highly intricate process with so many moving parts. The artist’s feedback is critical at each stage to ensure the mix aligns with their vision. The more complex the track, the more elements need to be balanced, which makes the artist’s perspective invaluable.

“To make collaboration smoother, I’ve been using tools like Audiomovers to work in real-time with artists remotely. This approach has been a game-changer when logistical challenges, such as time constraints or geographic distance, make attended sessions impossible. Virtual sessions allow the artist to be involved without needing to be physically present, and it can really be a lifesaver in those situations.

“On the mastering side, I still prefer to have the artist in the room whenever possible. There’s something powerful about making decisions together in real time, and it also provides an opportunity to educate the artist on the nuances of mastering. I find that when artists see what goes into the mastering process – how subtle adjustments can dramatically impact the final sound – it deepens their understanding of their own music. This knowledge makes them better at arranging, producing, and composing because they start to think more holistically about how their choices in the studio will translate into the final master.”

What are your thoughts on the rise of ‘AI powered’ instant mastering services? Have you tried any of these and do you think they represent a shift in the way mastering will work in the future?

“I’ve experimented with AI mastering out of sheer curiosity, but the results are always a hit or miss. The issue lies in how we perceive mastering. It’s not just about making music louder; it’s about having a fresh set of ears provide feedback and shape the sound based on the engineer’s ethos and aesthetic sensibilities. AI mastering reminds me of getting legal advice from ChatGPT – it might be fast and cheaper than hiring an actual lawyer, but it lacks the human insight necessary to properly contextualise all the nuances that make each situation unique. That’s what a human brain brings to the table, something an algorithm is never going to get right.

“Artists come to me for mastering because they value my input beyond just technical precision. They seek out my understanding of specific genres and cultures that aren’t always handled well by more mainstream mastering houses. Being deeply involved in these music communities, I know how vital it is to have someone who truly grasps the culture and aesthetic behind the music. I wouldn’t want someone unfamiliar with that context touching my own work, and I imagine most artists feel the same.”

Do you have any mixing or production tips you could share for musicians working in similar genres to yourself – who might not have access to high end studio gear?

“When I was first starting out, I only had a fairly basic setup with a guitar, a synth, and a couple of effect pedals. I made the most of the little gear I had back then and made it work for me. In fact, my first album as The Sight Below was entirely made with a thrift store Les Paul clone, an 808 drum machine, Line 6 DL4 delay pedals, and a Lexicon LXP-5. Everything ran directly into a Mackie VLZ 1402 mixer (that had seen better days) – all songs recorded live into my laptop.

“The truth is, you don’t need an arsenal of high-end studio gear to make inspiring music. Passion is by far more important. I believe scarce resources are truly the mother of invention. The key is to identify your limitations and use them as parameters to develop your unique aesthetic. What might seem like a flaw can actually become a valuable asset in your praxis. Instead of thinking, ‘If I had X piece of gear, I could do so much better music,’ focus on what you can create with the tools you already have, not what you wish you had. Equipment alone won’t fix a lack of inspiration.

The album’s final form was an exercise in perseverance and applying oneself: taking the time to explore ideas and develop them

“Creating music that is true to yourself and your vision will help you find your own way of doing things at your own pace. If your work is interesting, it will contribute something valuable to the larger collection of works out there, and thus, people will take notice. Most importantly: don’t forget to listen. Stay curious about music and the world in general, and never lose sight of why you started making music in the first place.”

If you had to name one or two things, what for you are the telltale signs of an amateurish or bad mixdown?

“Two immediate telltale signs of an amateurish or poorly executed mix for me are bad phase correlation and an inconsistent tonal balance. When phase issues are present, elements in the mix can cancel each other out, causing a loss of clarity and impact, most noticeable when a stereo mix completely collapses in mono. Similarly, a poorly managed stereo image can make a mix feel really disjointed.

“But the biggest telltale sign for me would be a mix in which elements don’t blend well together. I often reflect on Aaron Copland’s ‘four elements’: rhythm, melody, harmony, and tone. These four elements – three musical ones plus tones – are crucial for creating a well-balanced track. When these elements are harmoniously integrated, music can become infinitely unique and compelling to listen towards. In a successful mix, these elements work together seamlessly, ensuring that each part complements the others and contributes to a cohesive, sonically satisfying whole.”

Could you tell us a little about the creation of your new album FAÇADISMS. There are some fascinating textural drones throughout, what instruments and effects are you primarily using for these?

“Most of the textural drones you hear on my new album come from custom-made VST effect plugin patches and a looping system I’ve developed using Ableton Live and Max. My approach transforms the laptop into a dynamic instrument, allowing me to create and manipulate complex soundscapes on the fly as I play guitar or synths through this system.

“For this album, I mostly used my Travis Bean Designs 1000A guitar in Drop A tuning (which I learned from Stephen O’Malley) and a Prophet 5 synth, playing these instruments through my looping system and effect chains. The CV Tools in Max for Live played a crucial role in adding movement and depth to these textures. By modulating parameters on effect chains with LFOs, I can create evolving, immersive sounds where different effect units interact and harmonise with each other, producing rich and complex layers.”

Were there any new bits of gear or techniques that you worked with or found particularly inspiring while creating FAÇADISMS?

“Once a piece was ready, I’d export my stems from Ableton and then use ProTools for mixing. There I’d integrate both vintage and modern hardware. Vintage ‘90s gear like the Alesis MIDIVERB II and the Digitech DSP 128 added a unique character to my stems. Modern high-end units like my Bricasti M7 Reverb provided great spatialisation effects that enhanced the depth and ambience of the sounds.

“One of the most inspirational pieces of gear I used on this album was the CXM1978 by Chase Bliss. It allowed for further creative exploration of textures – I could run stems through the unit and improvise with it for a while, capturing different elements and recording them as I improvised with the unit.

“I also incorporated various guitar and bass amps, like my Sunn Sonaro and Vox AC-30, using reampers to run different stems through these amps. This technique helped me shape the tonal aspect of a track, adding a physicality to its sound. Running parts through multiple amps and experimenting with different settings contributed a lot to the album’s brutalist sound.

“The interplay between these elements – custom effects, looping systems, and diverse hardware – resulted in the sonic palette that defines the album, blending newer technology with more traditional sound design techniques.”

Could you tell us a little more about the compositional approach for the album?

“This album was a very long process that started all the way back in 2016, at least conceptually. While on tour in Italy that year, I started thinking of musical and non-musical ideas that will later become the foundation for FAÇADISMS. By 2020, the creative process was further influenced by my interest in brutalist architecture. Reading about brutalism’s emphasis on raw, unrefined aesthetics and its innovative use of materials provided me with new perspectives on structure and form for my compositions.

I devoted countless hours to improvisation, recording everything in real-time

“This inspiration led me to approach the album with a focus on creating a rawness that mirrored the brutalist ethos – where imperfections and bold, structural elements contribute to the overall artistic statement. I devoted countless hours to improvisation, recording everything in real-time. This process was essential for capturing spontaneous ideas and unexpected moments that often yielded compelling motifs.

“Once the improvisations were recorded, I shifted to editing. I reviewed hours of recordings to find melodic motifs and sections that stood out. These became the building blocks for the compositions. I expanded on these by adding layers of instrumentation and meticulously mapping MIDI to integrate various parts into the music.

“For this album, I forwent using a click track, instead relying on my internal sense of tempo to achieve a more fluid sense of time, in contrast to the overly quantised and gridded approach of modern music production. This allowed me to create a sonic palette that feels organic and harks back to the unrefined aesthetic of brutalist architecture. Of course, this can be very impractical too when you’re working with sequencers: I spent so many hours mapping MIDI notes and tempos on tracks so I could sync synthesisers to my guitar playing and vice versa.”

How did you work with the various collaborators on the album?

“This album benefited from a few innovative remote collaborations. For example, I worked with Hannah Elizabeth Cox and recorded her vocal improvisations in real-time from Boston, utilising Audiomovers and a rudimentary Mac screen-sharing app to run her recording sessions remotely from my studio in New York. I actually ended up running her vocals through some of my Ableton and Max patches, treating some of her takes as samples, manipulating the sound live and creating different textures with my looping system, basically improvising with her vocals and creating dense choirs with voice.

“With Julia Kent I used a different approach. Julia has an incredible sense of harmony and dynamics, so it was important for me to ensure that she had the space to contribute something authentic to her style. Once she laid down her cello parts and sent them back to me, I began the process of integrating them into the mix. I explored how her contributions could elevate the track. Instead of simply layering her performance on top, I carefully intertwined it with other elements, making sure her cello became the protagonist of the piece in many key sections.

“The last piece on the album was co-written with Kenyan sound artist KMRU. This piece started as a guitar improv I had recorded at a friend’s studio with the TB1000A and several amps linked together. Once I started to add all the parts KMRU wrote, I built a choir by looping and layering [Spanish artist] Yamila’s voice. The resulting track ended up sounding like something described by others as a, ‘soundtrack for the soul leaving the body, only to discover a void. Like the sound of the centre not holding, of shared illusions being dissolved in a tunnel of white light’.

“Despite the challenges of working remotely, the collaborative process was rewarding. The album’s final form was an exercise in perseverance and applying oneself: taking the time to explore ideas and develop them to their fullest potential. Through the process of making this album, I’ve come to find out creativity doesn’t just thrive in fleeting moments of inspiration – it flourishes in the commitment to seeing those ideas through, no matter the obstacles.”

FAÇADISMS by Rafael Anton Irisarri is out 8 November on Black Knoll Editions. Find out more about Black Knoll studios at the official website.