We make a fuss about finding distant worlds that look like Earth, and for good reason. But the coolest thing about alien planets is that sometimes they’re just completely, bizarrely, wonderfully alien.

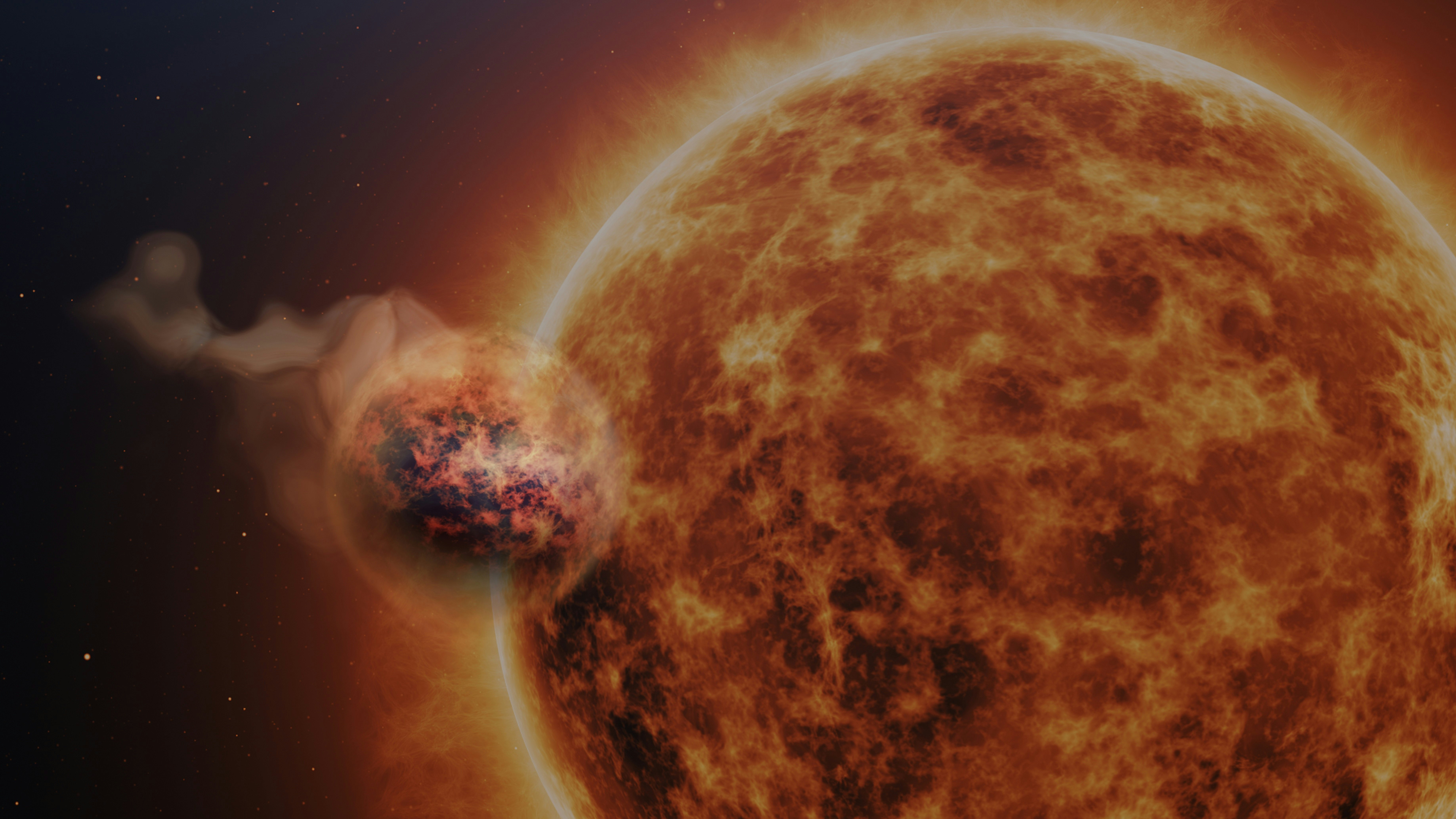

Consider WASP-107b. The gas giant is a gloriously weird planet. For one, it orbits its star backward, in what astronomers call a retrograde orbit. Based on data from the Keck Observatory, the giant planet has a long, glowing tail of helium trailing behind it, like the universe’s largest comet, because stellar wind is blowing parts of its atmosphere away. And according to new data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), it also rains molten sand. Like we said: gloriously weird.

Astronomer Leen Decin of the Catholic University of Leuven and her colleagues published their findings in the journal Nature.

Weird Doesn’t Even Begin to Cover It

Decin and her colleagues recently used JWST’s Mid InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) to peer deep into the atmosphere of gas giant WASP-107b, which orbits a star slightly smaller than our Sun about 200 light years away. As the planet’s orbit brings it between Earth and its star, MIRI measures the starlight filtering through WASP-107b’s atmosphere. In the MIRI data, Decin and her colleagues saw that WASP-107b’s atmosphere absorbed light at the same wavelengths as water vapor and sulfur dioxide, but that signal was sometimes hidden by dense clouds of silicate (also known as extremely tiny sand grains) in the planet’s upper atmosphere.

WASP-107b orbits its star, going the wrong way and tilted at a jaunty angle, once every six days. At that close range, the planet absorbs a lot of heat from its star, and when you heat gas, it spreads out. This means WASP-107b is about the same mass as Neptune, but it fills a sphere about the size of Jupiter. It’s light, fluffy, and nearly transparent down to surprising depths.

For astronomers, that means it’s possible to see starlight filtered through much deeper layers of WASP-107b’s atmosphere than they could see in a normal exoplanet, which is about 50 times deeper.

Based on the MIRI data, Decin and her colleagues suggest that vaporized silicate (imagine heating sand so much that it melts and then evaporates) in WASP-107b’s upper atmosphere cools and condenses into tiny particles, which form sandy clouds and eventually rain down into the planet’s depths. Deep in the gas giant’s interior, pressure keeps things much warmer, and the sand evaporates again and gets carried aloft into the upper atmosphere.

“This is very similar to the water vapor and cloud cycle on our own Earth, but with droplets made of sand,” says University of Amsterdam astronomer Michael Min, a coauthor of the recent study, in a statement.

Glitter Clouds and Endless Sandstorms

WASP-107b isn’t the only alien world where it rains sand (which may be the weirdest fact of all). Clouds of tiny quartz crystals — also made of silicate — glitter in the upper atmosphere of WASP-17, and VHS 1256b’s cloudy atmosphere is a constant roaring sandstorm. When astronomers first spotted giant gas planets orbiting distant stars, it was natural to compare them to our familiar neighbors, Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, and Uranus. But there’s nothing in our Solar System like WASP-107b or the other sandstorm worlds.

Perhaps ironically, this deeply alien world — thanks to its inflated atmosphere — is one of the few places outside our Solar System where astronomers have been able to see firsthand how heat and chemistry combine to create climate and weather patterns in the form of a weird sandy rain cycle.