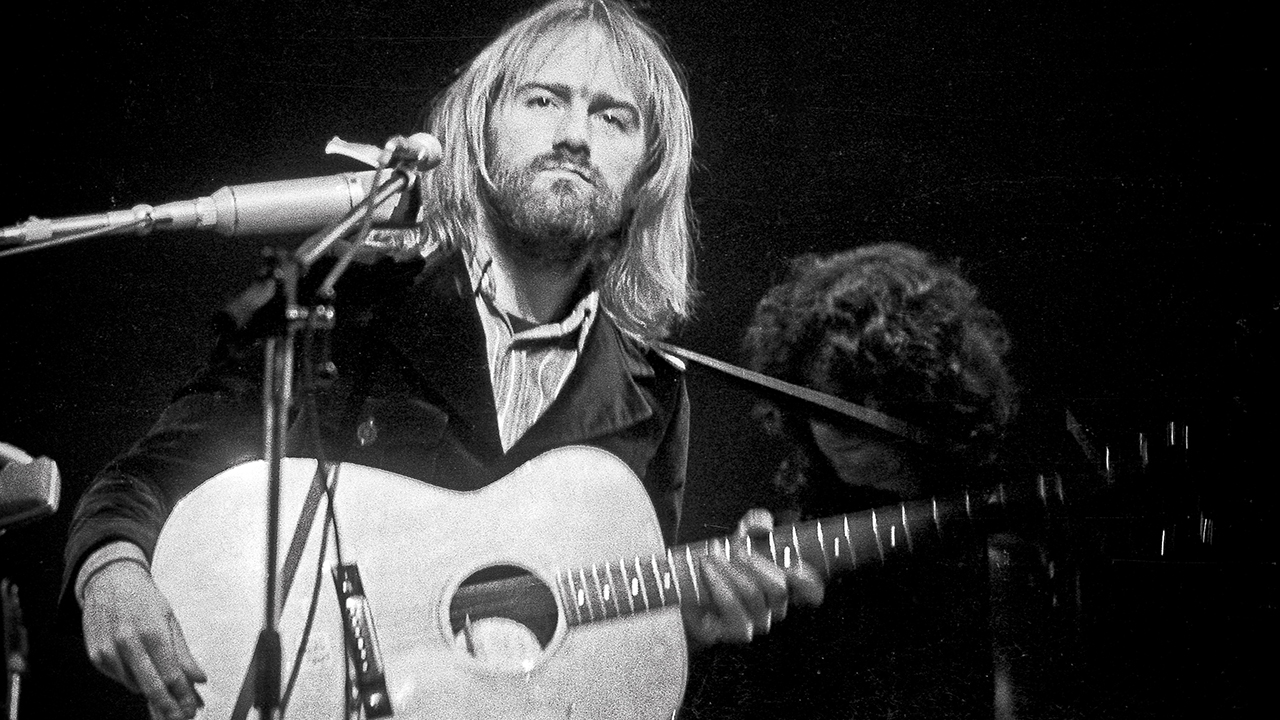

In 1971 revolutionary singer-songwriter Roy Harper was about to go deep into the world of concept rock – but his four-track opus got buried by his label. In 2011 Prog found out why.

There are many ways to describe Roy Harper, but ‘conventional’ has never been one of them. He emerged from London’s boho folk circuit of the 60s as a singer-songwriter of alarming intensity, motored by a mistrust of authority and an inalienable belief in everyone’s basic right to individual freedom. While other folkies were protesting the Vietnam War, Harper was railing against deeper societal ills. But then he was never really a folkie in any traditional sense.

Shaped by a traumatic early life – a fanatically religious stepmother, homelessness, prison, a spell in a mental institution – his music avoided the easy route too. Harper’s early albums were hallucinogenic things that skittered between poetry, revox-blues and psychedelia, as much prone to spliffed-up lunacy as they were to chilling autobiography and 17-minute songs about Patrick McGoohan. His underground status as a countercultural hero was finally seeping upwards by 1970, when his friendship with Led Zeppelin led to the touching tribute Hats Off To (Roy) Harper, which appeared on Led Zeppelin III that October.

He was by then managed by Peter Jenner, onetime custodian of Pink Floyd (who themselves would later invite Harper to sing Have A Cigar on the multi-platinum Wish You Were Here). Jenner had produced Harper’s previous opus, 1970’s wonderful Flat Baroque And Berserk, at Abbey Road. With the same studio again available, and a searing new set of compositions, Harper began making Stormcock. For once in his five-year recording career, he was able to fully focus on the job at hand.

The combined studio time of his first three albums – from 1966’s The Sophisticated Beggar to 1969’s Folkjokeopus – had been a week. “Flat Baroque And Berserk was where I was spreading wings and finding out exactly what could be done,” Harper tells Prog. “But then I saw a different light at the end of that record. I felt the time was right for me to do what I really wanted to, which was Stormcock.”

Adds Jenner, who again produced the album: “The Floyd were making things like Atom Heart Mother and Meddle; Zeppelin were making long tracks and The Who were doing Tommy. The spirit of the times was concept rock. Suddenly, in terms of songwriting, you weren’t restricted to three minutes or what was acceptable for radio.”

Stormcock was a masterpiece. Comprising just four songs, most featuring only Harper and his dizzying skill on acoustic and 12-string guitar, it was emotionally fierce and highly inventive. There were savage attacks on war, the judicial system, rock critics and religious dogma – among other things – alongside an anguished plea to save the planet. And, trading as S. Flavius Mercurius, Jimmy Page provided flashing lead guitar on the 12-and-a-half-minute The Same Old Rock. It remains Harper’s own personal highlight of Stormcock.

“Jimmy’s so intuitive,” he explains. “He finds things he can identify with, and that’s what he did on that song. It was just an atmosphere he created – it’s one of those things you just remember forever in your life. Jimmy elevated it into something else entirely.” It’s an astonishing piece of work all round, both men spinning soundwebs as complex as they are complementary.

I was told by one journalist, after Stormcock, that I was a megalomaniac. And it had a real intense effect on me

Roy Harper

Jenner believes Harper and Page shared a common understanding in the studio: “Page could feel where he was going and Roy would follow him. Page obviously liked working with Roy. And it got him away from being either the session man or the rock god. He was just able to play.”

The Same Old Rock is generally perceived as a scathing indictment of religion. In truth it’s less specific – it’s actually a discourse on the constrictive nature of any kind of dogmatic institution you care to name. Harper’s frustration at organisations which fail to acknowledge any alternative belief system is shared aloud: ‘You try to warn me that there’s only one combination / One new sling, the same old rock.’ Above all, the piece sounds like a plea for tolerance.

Hors D’Oeuvres is equally withering. The first verse is an eloquent diatribe against the judiciary, particularly the power invested in it. Harper makes it personal by alluding to the fact that the jury had somehow been out on his career ever since he began. Hors D’Oeuvres, like Stormcock itself, was both a statement of intent and statement for the defence. It was Harper laid very bare. The second verse is a ferocious attack on music critics. Anyone in particular? “There were one or two it was aimed at,” he concedes.

“But I don’t think naming names is going to help. That’s not fair. It’s like football referees: you can single one out but then the poor bugger has to go home.” There were consequences, though: “I was told by one journalist, after Stormcock, that I was a megalomaniac. And it had a real intense effect on me. I thought, ‘If that’s what people think about me, what am I going to do about it?’ It was like being compared favourably to Hitler. If there was any ethic I would want to avoid it would be national socialism.”

His reaction might well surprise those who view turn-of-the 70s Harper – a man seemingly possessed of uncommon self-belief – as impervious to the slings and arrows of rock journalism.

“I think that was because of the absolute authority I looked as though I was handing it out with,” he suggests. “But I felt very hurt at the time, because the way I saw myself was exactly the opposite of that. You always get a critic who’s able to open your guts up and spray your innards everywhere.”

It’s rather like an opera… Me And My Woman was almost three different songs fused together

David Bedford

Stormcock doesn’t get any less heavy further in. One Man Rock And Roll Band is both a meditation on the madness of war and the peace movement’s propensity for breaking out into full-scale riots. It’s all ably rendered by Harper’s fluid guitar accents and piano, with a delicacy and lightness of touch that belies its subject matter. In fact, it’s one of the defining features of the album itself.

For all its bite and burningly poetic anger, Stormcock is beautiful to listen to. There are flourishes of reverb, double-tracked harmonies, passages that billow between folk and jazz, rock and acoustic blues. As Jenner explains: “We were working at Abbey Road with people who’d all recorded The Beatles in one way or another. The influence of Phil Spector – who they’d all worked with too – meant there were certain traditions where we were working. With Stormcock, Roy managed to make a record that embraced a lot of prog rock aspects within the context of the sort of music he wrote.”

Nothing illustrates this quite like the sumptuous Me And My Woman, a 13-minute opus orchestrated by David Bedford, who’d also been involved with Flat Baroque And Berserk. It remains one of Harper’s greatest ever moments. “It’s rather like an opera,” Bedford says. “The themes and the basic riff keep recurring. I decided to give the verses a kind of baroque feel, then have these big sweeping strings for the chorus to differentiate the two. And they seemed to really like that. Me And My Woman was almost three different songs fused together.”

The song could be taken as an ornate love ballad, but it’s actually one of the first eco-protest songs – Harper warning of imminent environmental collapse in the face of the relentless pursuit of wealth and power. Stuffed with metaphor, it’s a song open to interpretation.

“Me And My Woman is about Mocy [Harper’s first wife],” posits Jenner. “Around that time Roy’s marriage was breaking up and I think it was a statement about how important she’d been with Nick [Roy’s son] and all the rest of it. But Roy had a wandering eye. So I think Me And My Woman was his paean of praise to her, which I think was wonderful. And it was about living with her down in Wiltshire. In many ways I think it was one of the happiest parts of his life and it’s a shame he didn’t settle down a bit more into that.”

I was distraught. I knew that if Stormcock had been taken at face value, it was a revolution in itself… a new direction for people to look in

Roy Harper

“It partly is about her,” Harper concedes. “But in my mind that song is always the question: ‘Me and my woman, what are we doing on this planet? Are we part of the ongoing fauna and flora or are we likely to last very much longer? Are we not making it very difficult for ourselves to carry on?’ I was making this point when I wrote it in 1970. People are still asking the same question – but it’s actually got a lot closer to the bone now. It’s still a huge question and one that remains unanswered.”

Released in May 1971, Stormcock should have been a flyaway success. But as with many things in Harper’s life, it was never quite that simple. The record company, whose execs had dipped in and out of the studio a couple of times, weren’t happy. “They wanted a single and there was no single appearing,” Harper recalls. “So even before the record was finished it was outlawed.” Not only did Harvest refuse to get behind it, assert Harper and Jenner, they claimed there was no budget for promotion either. It was the same in the US, where the suits at parent label Capitol just weren’t interested.

“They turned it down,” says Harper, “which effectively meant that it was a non-starter internationally. They were hard and fast pop men. Anything that was selling in millions they got behind, but they didn’t want to break new ground. That wasn’t in their remit. I was distraught, to be honest. I knew that if Stormcock had been taken at face value, it was a revolution in itself. It was a new direction for people to look in.”

It was a situation that also devastated Jenner. “Stormcock got virtually no promotion,” he says. “In hindsight, that’s one of the greatest disappointments in my life. It could have been a huge record, but they absolutely buried it. And that was a tragedy. It was Roy’s time but the boat just sailed away.”

Nevertheless, Stormcock remains undimmed by the years. Subsequent generations of musicians have hailed it as a hugely influential record. Kate Bush, for one, has long been an admirer, while Johnny Marr recently told The Guardian that “if ever there was a secret weapon of a record it would be Stormcock. If anyone thinks it might be a collection of lovely songs by some twee old folkie then they’d be mistaken. It’s intense and beautiful and clever: [Bowie’s] Hunky Dory’s big, badder brother.”

As time goes by it looms larger in my personal history

Peter Jenner

California’s harp-wielding phenomenon Joanna Newsom is another greatly indebted to Stormcock. A prime influence on her astonishing 2006 breakthrough Ys, she invited Harper to support her at the Royal Albert Hall the following year, where he performed Stormcock in its entirety. The pair are now fast friends. Another convert is Fleet Foxes’ leader Robin Pecknold, who has stated that the 12-string sections on their much-anticipated new album were partly shaped by Stormcock.

“It’s a great unrecognised masterpiece,” concludes Peter Jenner. “And as time goes by it looms larger in my personal history. I imagine people will still be listening to it and talking about it 50 years from now.”