When the Israeli government cut off supplies of water to the Gaza Strip following Hamas’s brutal attack, it put the role of water within human conflict into particularly sharp relief.

Debate on the notion of “water wars” has raged among water experts for nearly four decades. In 1988, Boutros Boutros-Ghali (who later became secretary general of the United Nations) said that the next set of wars will be over water. However, the years since have seen no clear instances of wars fought over water, making such a bold statement seem somewhat misguided in hindsight.

So, can the converse be true? Can the sharing of water across borders be a mechanism for creating lasting peace, even if what water is available is scarce?

Managing water scarcity

The Jordan River Basin is, by any reasonable metric, one of the most parched areas of the world. All countries in the region have water availability per person that’s well below the global threshold to be labelled as “water scarce.”

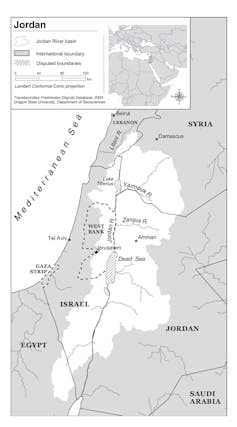

As with all watersheds, the river we see on the surface is only one part of a wider basin that, in the case of the Jordan River, is about the size of Turkey (almost 19,000 square kilometres). This basin drains into the Dead Sea and its water resources are shared by Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria.

Each has had its own approach for dealing with this water scarcity. This has had profound consequences for their social and economic development and for environmental protection.

Jordan and Syria have struggled with water management, which is partly reflected in lower economic productivity (US$4,100 and US$1,100 GDP per capita respectively).

In contrast, Israel has utilized high-technology solutions to manage its water and innovated considerably in agricultural applications, becoming the world leader in drip irrigation. Such technological achievements are reflected in its comparatively high US$42,000 GDP per capita.

A history of co-operation (and conflict)

With water scarcity comes intense competition for limited water resources. Typically, such competition not only exists across international borders but among different sectors within a country. In countless situations of internationally shared waters, countries have sat across the table with each other and found ways to manage water challenges.

The classic example of such collaboration is the Indus Water Treaty between bitter rivals India and Pakistan, which has lasted since 1960 through wars and tense diplomatic relations between the two countries.

In the Jordan River basin, a poignant example is the “picnic-table conversations” between Jordan and Israel — a joint water management process that started in 1953 and continued even when the two countries were officially at war from 1948 until the Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty in 1994.

A formal water-sharing agreement between Israel and Jordan on the Yarmouk River, a tributary of the Jordan River, can be found in Annex II of the 1994 treaty. While the agreement is far from perfect and has been criticized for not giving due consideration to Palestinian usage downstream, it has endured.

The agreement does not mention the Golan Heights, and yet it allows Israel to use water emanating from it. Another 1984 agreement between Jordan and Syria on the Yarmouk River is also in place and was developed to allow construction of the El Wahdat (Unity) Dam.

Read more: Israel is hoarding the Jordan River – it's time to share the water

But co-operative management of shared waters has not always happened smoothly in the Jordan River basin. For example, there was intense conflict on water sharing between Lebanon and Israel, after the latter’s withdrawal from the Lebanese territory in 2000. Lebanon wanted to install Wazzani wells in the upper Jordan River area that could potentially impact groundwater flow into Israel.

Each side accused the other of acting in bad faith and in contravention of international law. This situation was eventually resolved through the intervention of the European Union and the United States, and the wells were installed.

Overall, these examples lend credence to the argument that water-sharing across international borders can be used to foster co-operation. Importantly, these technical discussions also open the door for conducting indirect dialogue on other political matters. Such “Track-II diplomacy” has been widely used elsewhere, and the picnic-table conversations were a prime example in the Jordan River Basin.

Thinking outside the box

There is another remarkable example of how Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority came together to develop a region-wide initiative despite the ebb and flow of political discourse.

The innovative idea of transferring water from the Red Sea to Dead Sea (RSDS) was originally conceived in 1998 to transfer water to salvage the fast-shrinking Dead Sea while generating energy due to the 500-metre drop in elevation between the two seas.

That energy could be used to desalinate part of the water for use in Jordan as well as in Israel and Palestine. This project would create employment opportunities for Jordan, generate much-needed water and energy and could become a symbol of peace.

The agreement for the RSDS initiative was signed in 2005 between Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority through the mediation of the World Bank. The main challenge has been to mobilize the $11 billion needed to complete this project, despite the development of a full-blown implementation program in 2013.

Effective sharing of Jordan River’s waters can be a pathway to lasting peace in the region. The RSDS project may not be revived anytime soon because of the current political turmoil and armed conflict in the region. Nonetheless, it has demonstrated that imaginative out-of-the-box thinking can lead to win-win solutions and bring bitter rivals to the table.

What is clear is that active dialogue, and co-operation on water management, must be made part of the gradual progress towards peace.

Zafar Adeel does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.