A novelist who was somewhat very surprisingly shortlisted yesterday for the Ockham book awards investigates the possibilities of time travel

What is this strange thing we call time? This thing that won’t let me hold on to moments that most matter, that’s greying my hair and blurring my eyesight? That amorphous phenomenon that has replaced those two preschoolers, who used to run to me with excitement when I walked through the front door, with these high schoolers, eyes glued to their phones (when not rolling at my jokes)?

I got a taste of the answer, or at least got better questions, when I visited the Centre for Time at the University of Sydney to do some research for my novel Entanglement, a book I envisioned less as science fiction than science-in-fiction. It looked, despite its intriguing name, like any set of academic offices—except for the strange clock. Its inexpensive wooden frame (plywood or something similar) was painted to evoke a grandfather clock, though in garish colours.

But what was remarkable about it—what made it amusing and apt for its setting—was the analogue clock face itself. Its hands ran counterclockwise. That is, it ran forward—the 5 followed 6, which was followed by 7—but it ran in the opposite direction to which we’re accustomed, so that 5 was to the left of 6, which was to the left of 7.

It was dizzying and disorienting to read it. As a researcher was settling me into my cubicle, he gave me some advice: Don’t think about it too hard and you’ll know what time it is; think about it too much and you’ll confuse yourself. As it turns out, this more or less describes our relationship with time as expressed by St Augustine some 1800 years ago. He wrote, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.”

Which is to say, if you think about time too hard it starts to make less sense, like that game where you repeat a familiar word over and over until it loses meaning. We use all sorts of terms to describe it in ways that make sense intuitively and which we don’t think about too much: Time “passes” or “flies” or “flows”—it’s “like a river.” It feels that way to me sometimes, like I’m in a boat moving swiftly by a current as events—my children’s births, their first days of school—grow more distant. But when you start to think more critically, these descriptions make less sense.

I was a little embarrassed to raise the question of time travel with the experts at the Centre for Time, but as it happens they talk about it all the time and were happy to discuss it at length

If time moves (flows, flies, passes), for instance, then it must have a speed. But speed is expressed as distance in relation to time (e.g. kilometres per hour). So if time moves, we are describing time in terms of time—that is, time travels at a certain time. The best we can say is that time moves at precisely one second per second. That doesn’t tell us much. And what does it move in, exactly?

We also treat time as uniform, when it isn’t. I’m not talking about how the days seem to crawl when you’re eagerly anticipating a holiday or how they zip by when you’re finally there. Or the way childhood is so long on the inside, but so short from the outside—watching your own children go through it. Time actually does differ for people moving at different speeds or living at different heights. Einstein realised this when he was crafting his theories of relativity. Once he determined that the speed of light is constant, it came together: if light’s speed is constant, then time is relative to where we are standing.

Imagine, Einstein suggested, someone standing on a platform watching lightning strike railroad tracks simultaneously at 9 pm—one strike behind a moving train, the other ahead of it. To someone on the train, those strikes would not be simultaneous. That’s because the train would be moving toward one of the strikes and away from the other; the light from the one ahead would reach the passenger first (the effect is more evident the faster the train goes). Clearly, the strike behind the train would be visible to the passenger, and would therefore occur, later. (For a more visual explanation, try Nova’s here. Or for a version with more dramatic music, try this.)

It’s not that the passenger is late in seeing it—it’s that their sense of when those strikes occur (one after the other) is just as accurate as the observer’s sense of when those occur from their standpoint on the platform (that is, that they were simultaneous). As for height, time moves more swiftly at the top of a mountain than at sea level. Not noticeably—but measurably. Experiments support it. Actually, it’s also true if you move your clock from the bedside table to a high shelf, though you really do need a very good clock to see it.

Somewhat stranger than this, to me at least, is the question of how real the past and future are. Most of us have an intuitive sense that events in the past (e.g. the French Revolution) are no longer happening and that the future doesn’t exist until we, well, get there. Or, I guess, get then. Which of course, won’t be then any longer, as it will be now. This corresponds with what has been called the “tensed” theory of time or “presentism.” But there are also proponents of what’s called the “block universe” or sometimes “eternalism.” By that way of thinking, the past, present and future all exist.

I’m tempted to say they all “exist simultaneously” or “exist now,” but that gets us into some confusing time territory since it would mean time would have to exist in some other time (that is, how could the past and present exist “now”—simultaneously?). A better way to think of it is spatially or geographically. Just because you live in Auckland and can’t see New Delhi or New York does not mean they no longer exist. The moment of your birth, what you are doing right now, and the moment of your death are all equally real—at least, they are if you’re a block time kind of person. It might sound crazy and have disturbing implications for free will. But many argue that Einstein’s relativity would tend to support the block universe.

This is not to detract from the mindfulness notion that all we have is the present moment, that it is important to live in the present. How often I’m reminded to be present at the dinner table—my mind having just returned from replaying a regret or catastrophising some unlikely event, my wife and kids staring at me with concern as I ask a question they have just answered. So far, I have been forgiven.

Still, the past and future beckon. A natural question: Since Aucklanders can visit New Delhi or New York (pandemic issues notwithstanding), can we similarly in the spatialised block universe visit the past and/or the future? I suppose that is what I wanted to know when I visited the Centre for Time, where I stayed for three weeks (if time exists at all—Julian Barbour says it does not). That is, is time travel possible? I was a little embarrassed to raise the question with the time experts there, but as it happens they talk about it all the time and were happy to discuss it at length over coffees or in graduate student seminars they let me attend.

The answer, as it turns out, is yes-ish—though just theoretically, and with caveats and plenty of objections. Travelling quite a distance into the future is theoretically possible, so long as you have a broad view of what time travel is. As David Lewis put it, someone is time travelling if “the separation in time between departure and arrival does not equal the duration of his journey.” Thanks to Einstein, we know that if you get on a rocket and travel at some good proportion of the speed of light, time will pass much more slowly for you then for the rest of us here on Earth. When you return, a lot more time will have passed—we’ll have aged considerably more than you (or have long since passed away, depending on how fast you were travelling). So from your perspective, you’ve travelled into the future. That’s not as cool as stepping into a contraption with lots of lights and dials that transports you immediately into a future hundreds of years from now. But it qualifies.

And the past? Trickier, but some have suggested it may be possible to use the same going-really-fast-and-return principle if we apply it to a wormhole. If you’ve watched Star Trek, you know that a wormhole is a theoretical short-cut through space—it has an entrance/exit in two different parts of space. Imagine we figure out a way to create such a wormhole, one large enough to fly through. We leave one end of it near the earth and find a way to move the other end at really high speeds (e.g. attach it to a rocket).

Remember, time for those chrononauts (why not?) trucking the wormhole at those speeds will be slower—so when they return with their end to our neighbourhood, a lot more time has passed on Earth than for them. From their perspective, they are in the future. Maybe everyone they know is elderly. Maybe everyone they knew has long since died.

But if they step into the section of the wormhole they’ve been flying around, they come out of the other side back in time. (Have at the maths here.) The rub is that the farthest you can go back is to a point after you’ve created the wormhole. And that’s setting aside all the reasons to doubt we’d ever be able to create such a wormhole.

“I gave a party for time-travellers," said Stephen Hawking, "but I didn't send out the invitations until after the party”

Of course, there are many other reasons to doubt time travel is possible. As Stephen Hawking observed, if time travel is possible, why aren’t we over-run with time tourists? Good question: Why aren’t they pulling out their iPhone 3,937’s to snap selfies in front of all of us in our old-fashioned eyeglasses and electric cars? Hawking was a true time travel sceptic. He reportedly said he had “experimental evidence” that time travel isn’t possible: “I gave a party for time-travellers, but I didn't send out the invitations until after the party. I sat there a long time, but no one came.”

Or perhaps time travellers are all around us. Would you tell someone you were from the future? Good luck with that. And as Carl Sagan put it, “Then there's the possibility that they're here alright, but we don't see them. They have perfect invisibility cloaks or something. If they have such highly developed technology, then why not? Then there's the possibility that they're here and we do see them, but we call them something else—UFOs or ghosts or hobgoblins or fairies or something like that.” Anyway, who says time travellers would accept an insultingly belated invitation to Hawking’s party?

If time travellers are all around us in their invisibility cloaks, could they change their past, create a new future? Kristie Miller, joint director of the Centre for Time, writes: “No. That would create a contradiction, and there are no contradictions.” You’d be able to do things in the past, she explains. It’s just that “when I travel to the past I don't change it, I just make it the way it is, and always has been.” Hawking himself famously proposed the “chronology protection conjecture”—a feature of the universe that “makes the world safe for historians.”

Still, the heart—and fiction, which is where the heart so often resides—scoffs at such sentiments. When I’m asked what led me to write Entanglement, I recall the moment some years ago that inspired it. It was a summer’s day. I was standing just outside my house, my family waiting for me inside, and felt, suddenly, as though I’d come back from the future, some darker time—though what the future was I didn’t know. My kids are so young again, I remember thinking. My wife and I are amazingly young, too.

I felt like I had been given another chance. I thought, There are so many mistakes I hadn’t yet made. It was a strange and powerful feeling, though it didn’t last—the moment passed. Or maybe the moment is still and eternally there in its little corner of the block universe. As are my young children, waiting just past the front door to throw themselves into their father’s arms to welcome him back from wherever he has been.

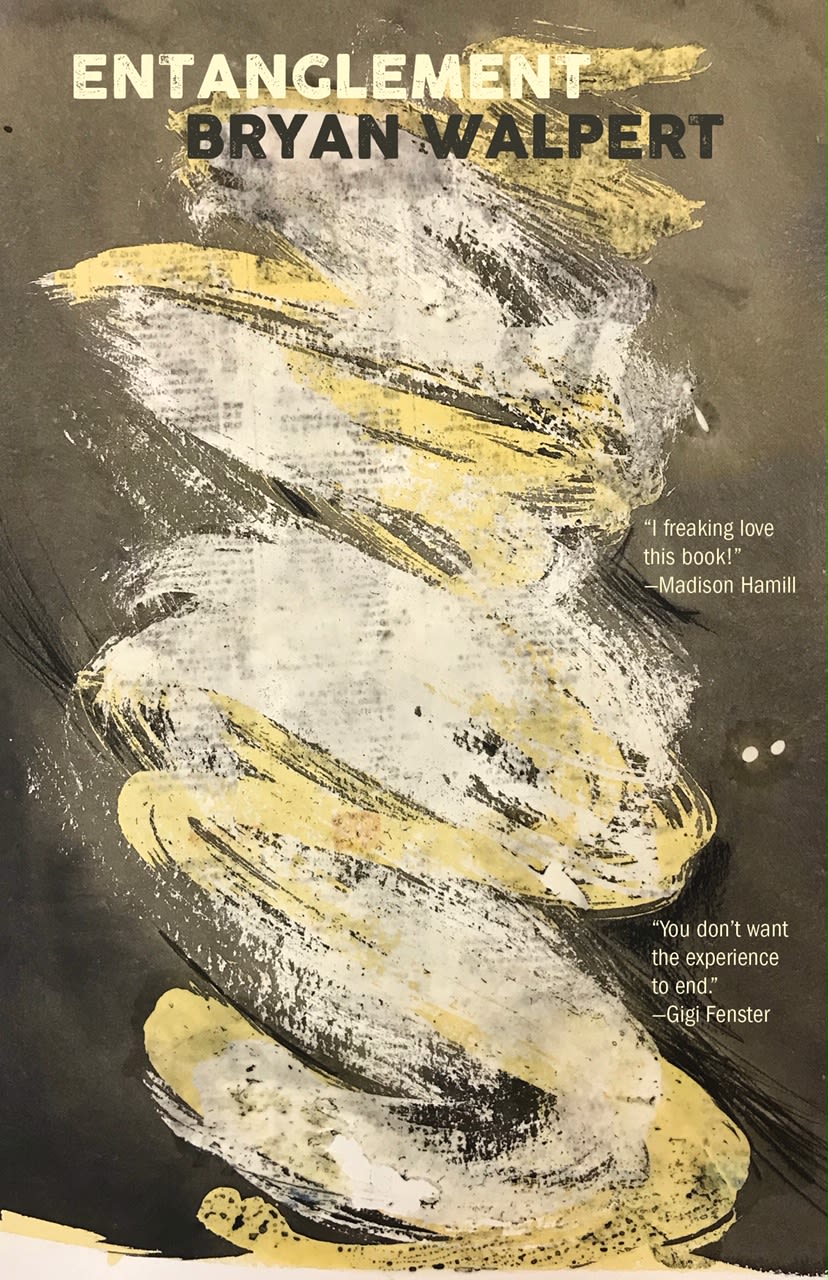

Entanglement by Bryan Walpert (Mākaro Press, $35) has been shortlisted for the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction at the 2022 Ockham New Zealand national book awards.