The last year has been a re-education about the primary sector, writes Vincent Heeringa. It’s been humbling and instructive, meeting incredible entrepreneurs, progressive farmers, and people who give a damn about real food and the true meaning of wealth

You’ve heard the phrase so often it’s become a cliche: New Zealand’s primary sector must move from ‘volume to value’. We must shift from being low-cost, commodity producers – think logs, carcasses, bins of fruit – to quality food and fibre producers, achieving a premium for our manufactures.

Since the 1970s, adding value has been the subject of working groups, white papers, training courses, bootcamps and fireside chats.

So, have we? After so many papers and pow-wows, is the volume-to-value story actually happening?

I’ve been curious about this for a while. When we founded Idealog in 2004 we featured a new company, Synlait, which was going to do milk differently – making food ingredients and pharmaceuticals, not just dumb milk powder.

Idealog championed brands that took commodities and added value – jumpers from wool (Icebreaker), fuel from CO2 (Lanzatech) and Greek yoghurt from milk powder (Dairy Collective). To my mind there was no value until value was added. To borrow from Animal Farm it was commodities bad, value-added good.

Better yet, we said, let’s ditch the farm and build a tech economy.

What did Sir Paul Callaghan say – it would take five Fonterras to catch up to Australia and by then we’d run out of land? Just start another Xero, bro.

And if we must have a primary sector then let’s at least be a Nestlé, making packaged goods and infant formula.

A few years have passed and a bit of life has knocked the edge off my arrogance. That and wondering where my delicious, carbon-zero, sustainably sourced steaks might come from. The fact is, New Zealand is quite good at making food and no amount of raging by a journalist is going to change that. Thank goodness.

So I’ve been thinking. The volume-to-value idea was a good one – higher prices, higher wages, smarter economy and all that. Is it still relevant and has it happened?

I decided to have a look.

The last year has been a re-education for me about the primary sector. It’s been humbling and instructive. I’ve met incredible entrepreneurs, progressive farmers, and people who give a damn about real food and the true meaning of wealth.

I’ve been lucky to help set up a programme to explore and expand on the topic – The Value Project – with research from the AERU and funded by Our Land and Water. It’s got a growing library of case studies and thoughtful discussion about where and how value is made.

Meanwhile, to speed up the story, here’s my lesson about the primary sector value in five graphs.

Let’s answer the first question: is the value to volume story happening? The short answer is yes – slowly, steadily and without much fanfare. It could be faster and we now have the added challenge of operating within planetary boundaries. But the overall story is good. Let’s start with these graphs.

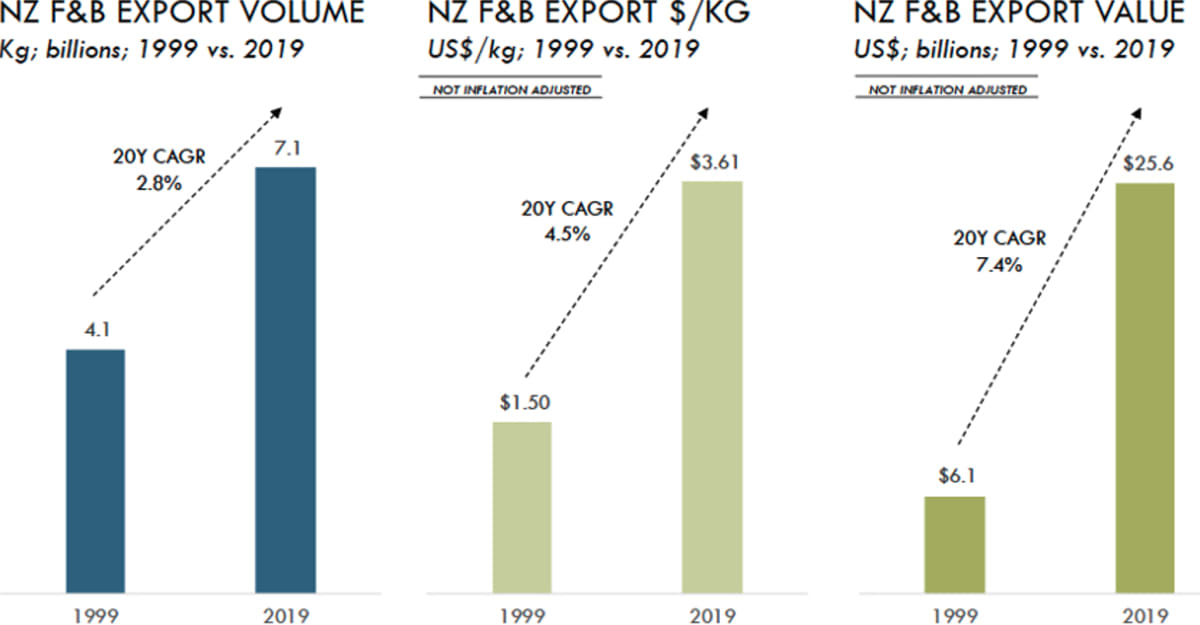

The three charts show an increase in volume (left) and value (middle) and combined total (right) of food and beverage exports. The result is impressive: a four-fold increase in 20 years. Now, just under half of that growth comes from inflation. But the bit that’s worth noticing is the outsize growth in value: 4.5 percent versus 2.8 percent for volume. We are charging almost two-and-a-half times as much per kilogram for food exports compared with 20 years ago. Yet we’re growing the volume by half that.

Are we moving from volume to value? Yes we are.

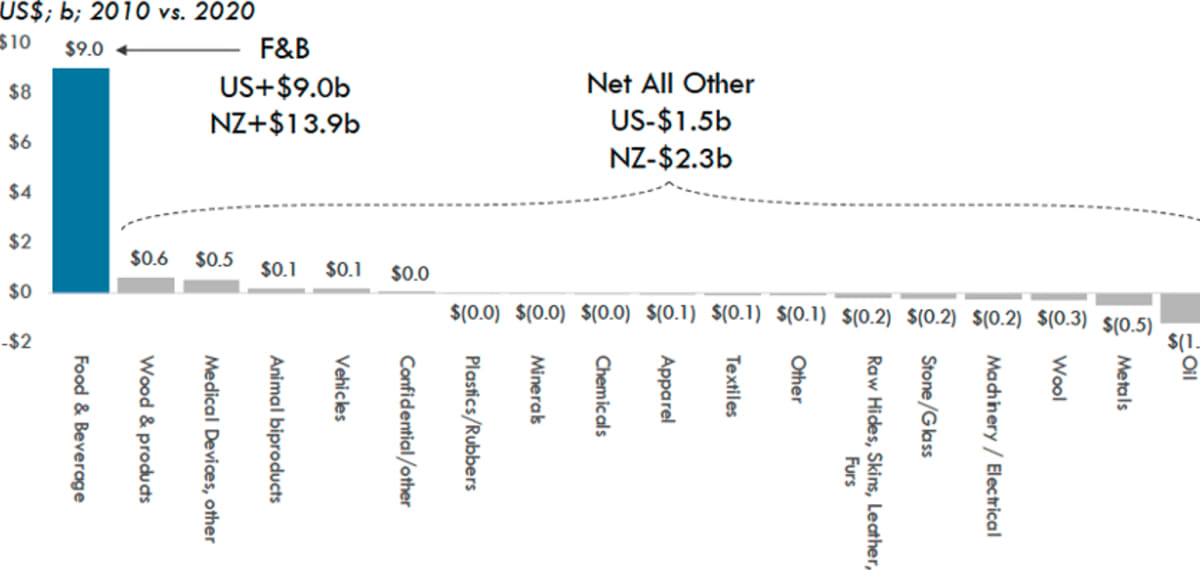

The effect is reflected in our export figures. Food dominates. We are indeed excellent food producers. The next graph shows just how outsized the growth in food and beverage has been, especially compared with other commodities.

10-year net change in NZ exports

So far so good. But where has that value come from? Is it the much-vaunted added value processes of turning commodities to branded snacks? Or is technology making it cheaper to produce? Is it improved genetics? Better marketing? Responding to government regulation? Heroic entrepreneurs? Industry cooperation?

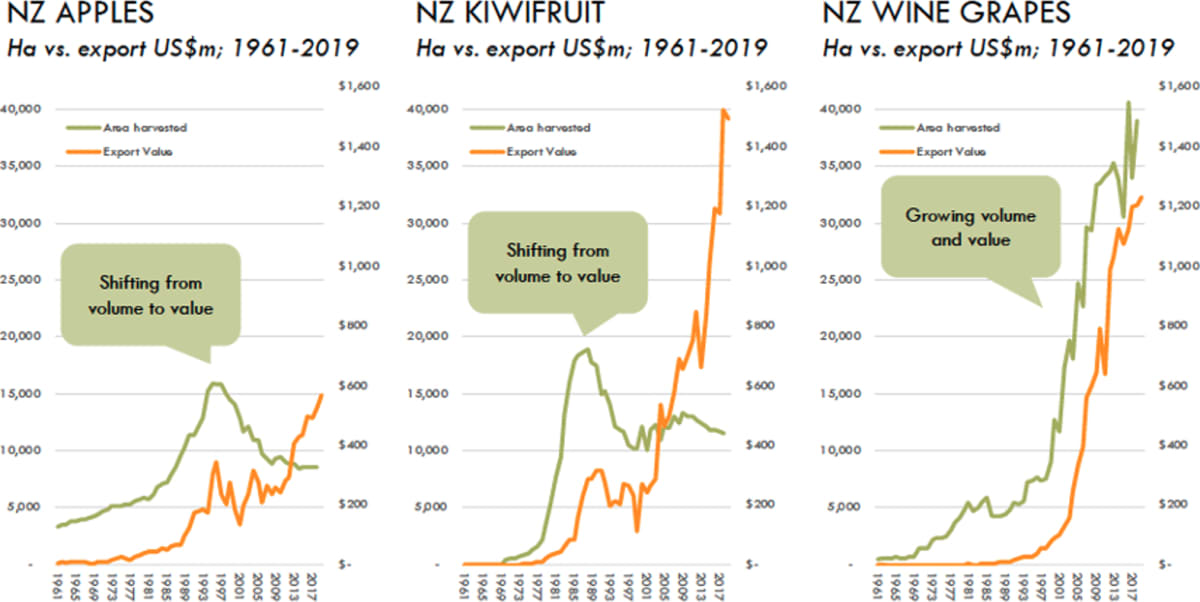

The answer, of course, is all the above. In almost every segment of the food and beverage sector there are minor miracles happening to make more from less. Take sheep. The numbers have halved since 1990 while sales of lamb have stayed the same – an 88% increase in productivity. Same with apples and kiwifruit – see the chart below. We’re getting more from less.

In wine, value growth has outpaced volume growth – we’re getting more from more.

Even dairy, our biggest commodity industry, has a value story to tell. Some 79% of our exports by volume is dairy. But infant formula, a value-added product, has increased from $52 million in 2004 to $1.5 billion in 2020. It’s forecast by MPI to top $2.5b by 2025.

Many roads to Rome

Tim Morris from Coriolis Research, the source of these charts, says there’s no single way to road to value. “You can create value by being the most efficient producer, which is what New Zealand has traditionally been good at.” (Think about those sheep numbers.)

“But there are many other ways. Lobster has high value because of scarcity. Moët & Chandon has higher value because of brand perception. Medicinal honey can charge a premium because it has credible therapeutic claims. A packaged meal can charge more than the sum of its ingredients because it solves the convenience problem.”

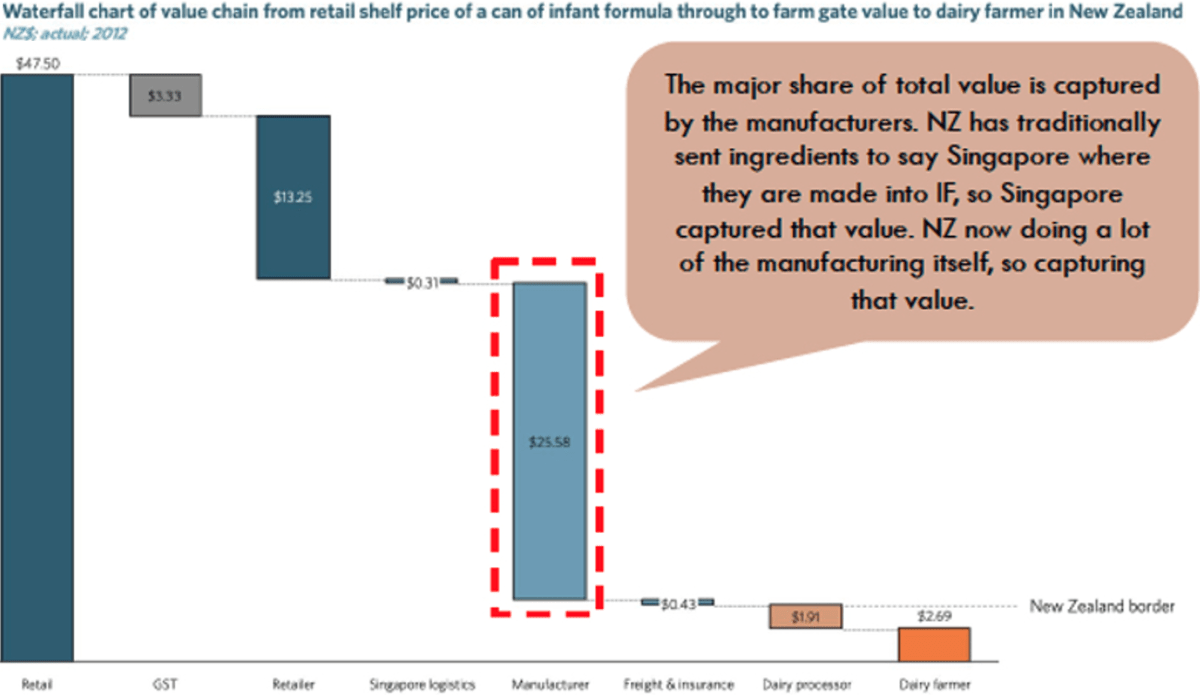

In the case of infant formula the value was being lost because it was manufactured overseas. Some of that processing is now done in New Zealand and more of that value is retained here.

Infant formula value chain – mark-up by stage

This is good news for New Zealand producers. They will come at the value problem from different places, with different products, selling to different markets.

Perhaps the question is not how to create value, but where to start.

Research from the Agribusiness Economy Research Unit (AERU), funded by Our Land and Water, provides some clues. In the past five years the unit has studied successful primary sector companies from industries as diverse as kiwifruit, wine, seafood, meat, dairy, jewelry and even cosmetics. Their question: what attributes set these companies apart? The team was agnostic about what these companies made (the product) but focused on how these companies behave, to understand what producers must do to achieve such a premium position.

The answer is that they established strong, market-oriented value chains, not merely supply chains. What’s the difference?

“A value chain looks at the consumer first,” says Professor Caroline Saunders, director of the research unit. “The value is created by the consumer, so these companies find out what they are really willing to pay for, what attributes they are looking for, and then bring that down through the value chain and make sure that fair reward goes to the New Zealand producers.”

New Zealand has traditionally been good at logistics and ensuring product quality, but not that good at market orientation.

A second attribute of these exemplar companies is their commitment to shared values. Deputy director of the AERU, Professor Paul Dalziel, explains: “New Zealand has always been determined to produce food to a high standard. But the standards keep rising. The aim now is to produce food, beverages and fibre within planetary boundaries – and with social and ethical standards met and by providing a great experience for the final consumer.” He says the inclusion of values – social, environmental, ethical, and experiential – is accelerating New Zealand’s progression from a commodity producer to a premium exporter.

A third attribute is the strong collaboration between all the players in the value chain. This includes knowledge sharing and a commitment to standards. It implies no one player dominates. “There can be a leader in the value chain but interestingly it’s not usually the one that has the power. You might think a big supermarket chain would have the power, and they do to a degree, but they allow leadership from the people who were making the stuff,” says Saunders.

She points to Zespri as a good example of leadership in terms of sustainability and innovation. “The people with power – the retailers – still want products at a competitive price. But if you have a value proposition for a higher price (better genetics) and market research (better insights) that can back that up, they are more likely to put it on the shelf.”

Good things take time

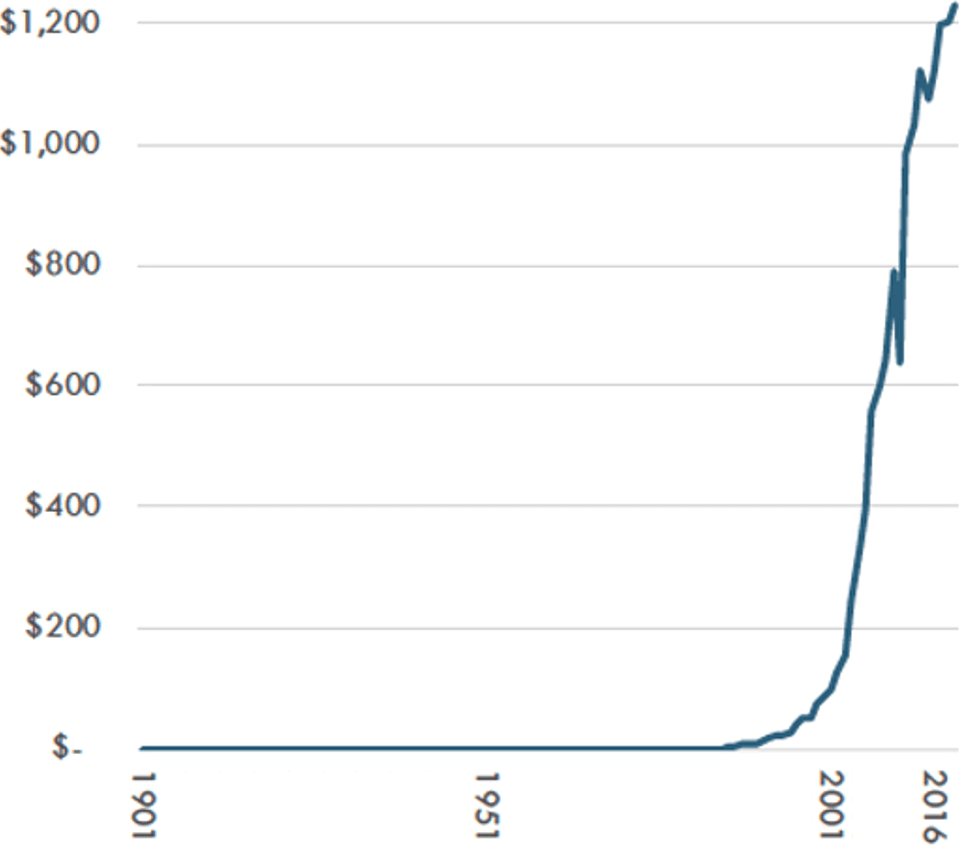

The volume-to-value is story is a slow burn. For those who wish to speed it up, it’s worth remembering that wine languished as an industry for 100 years. In 1895, expert consultant viticulturist and oenologist Romeo Bragato concluded that New Zealand and the Wairarapa, in particular, were “pre-eminently suited to viticulture”. It wasn’t until 1979 that the first Sauvignon blanc was planted. Cloudy Bay won international acclaim six years later. Yet as the chart below shows, it took another 14 years before we see the start of the explosive growth in exports we know today.

New Zealand wine exports (US$ million)

“You don’t create an industry overnight, especially in the primary sector,” says Tim Morris. “An industry is an ecosystem with many parts all working in concert. The wine industry took so long to be established because ecosystems by their nature take a long time to evolve.”

The AERU research suggests that it’s the health of the value chain that allows individual companies to grow. “Our research shows that it’s the level of cooperation and coordination within a value chain that helps companies succeed. The international literature shows that success is now a fight between value chains and value chains, not product versus product,” remarks Dalziel.

That change requires patience and persistence. And as with wine, we know that New Zealand can do it, and do it well. It’s not in seaweed, son, it’s in the collaboration.