Legal language, or “legalese”, is notoriously hard to understand. Legalese contains more difficult linguistic structures and unusual word choices than most other styles of writing, including non-fiction, news media and even complex academic texts.

The convoluted structure of many legal sentences can make it tough to understand and remember legal obligations. Even lawyers don’t like legal language. So why does it work this way?

In a new study with my colleagues Eric Martínez (University of Chicago) and Edward Gibson (MIT), we found that even laypeople resort to legalese when asked to write laws – which suggests the complexity of legal language may be a kind of ritual that helps give the law its power.

Stuffing sentences inside other sentences

One of the main reasons readers struggle with legal texts is a particular linguistic feature called “centre embedding”.

Centre embedding occurs when one sentence is placed inside another sentence. For example, in the sentence “the cat that chased the mouse avoided the dog” the sentence “the cat chased the mouse” is placed into the middle of the sentence “the cat avoided the dog”.

While this example sentence is fairly short, the sentences in legalese are often much longer. Take for example this drunk-driving law from Massachusetts, in which we bold the main sentence:

Whoever, upon any way or in any place to which the public has a right of access, or upon any way or in any place to which members of the public have access as invitees or licensees, operates a motor vehicle with a percentage, by weight, of alcohol in their blood of eight one-hundredths or greater, or while under the influence of intoxicating liquor, or of marijuana, narcotic drugs, depressants, or stimulant substances, all as defined in section one of chapter ninety-four C, or while under the influence from smelling or inhaling the fumes of any substance having the property of releasing toxic vapors as defined in section 18 of chapter 270 shall be punished by a fine of not less than five hundred nor more than five thousand dollars or by imprisonment for not more than two and one-half years, or both such fine and imprisonment.“

Centre-embedded sentences are difficult to process because readers have to remember what happened in the outside (bold) sentence while they’re reading the inside sentence. The reading difficulty increases with the distance between the words that depend on each other. (In the quoted sentence above, that’s ”Whoever“ and ”shall“.)

Stubbornly convoluted

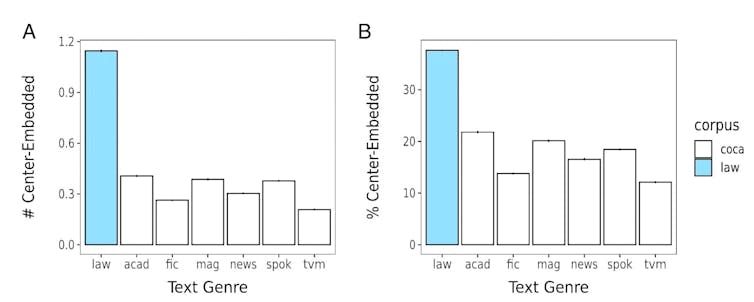

In our new study, we analysed the 2021 edition of the US legal code, the official compilation of all federal legislation currently in force. We then compared the results with other genres in a representative body of writing in English.

We found centre embedding is far more common in these laws than in other kinds of text.

We also found the "dependency length” – the distance between words that depend on each other – was also much longer.

In the United States (and elsewhere), there have been repeated efforts to write laws in “plain language”. However, our earlier research has found that the prevalence of centre embedding and other difficult linguistic structures in US law has changed little since at least 1950.

Why do lawyers use legalese?

Why is legal language so resistant to change? To find out, we need to know why lawyers are using legalese in the first place.

Perhaps laws written in legalese are more enforceable than simpler texts, or maybe writing in complex language improves a lawyer’s career prospects or makes clients trust them more. These don’t seem to be the case.

Research has shown that lawyers believe texts written in legalese are no more enforceable than plain-English texts with the same content. They also believe using plain English is likely to improve their career prospects and make clients happier.

Two more possible reasons

We also investigated two more possible reasons for using legalese.

The first is the “copy and edit” hypothesis: because legal contracts often address similar circumstances to other contracts, lawyers may copy templates and simply edit the details. Difficult structures such as centre embedding might be unconsciously copied in the template, or added as the lawyer iteratively edits drafts for their client.

The second is the “magic spell” hypothesis. Much like a magic spell, the purpose of legal language is to change the world rather than simply describe it.

This kind of “performative language” is often accompanied by a ritual or some distinctive linguistic feature. Magic spells, for instance, might be highlighted with rhyme (“double, double, toil and trouble”) or archaic roots (“wingardium leviosa”).

According to this hypothesis, difficult structures such as centre embedding may be used to highlight the performative nature of legal text.

The magic spell hypothesis

To test these hypotheses, we provided a group of 286 non-lawyers the legal content from US laws and asked them to write either laws, stories about breaking the law, or helpful explanations of a law to a tourist.

For half of the trials, the complete legal content was provided to the participant from the start. On the other trials, we hid some of the legal content from participants at first. After they submitted a draft, we surprised them with additional content to mimic the editing process of lawyers.

In line with the magic spell hypothesis, participants used more centre-embedded structures writing laws than when writing stories or explanations of laws. In contrast with the copy-and-edit hypothesis, participants did not include more centre embedding when they were asked to edit their text than when writing from scratch.

These results suggest that the difficulty to process linguistic structures in legal text, like centre embedding, serve as a cue to the performative, world-altering, nature of the text.

What now?

If laws really are like magic spells, it’s good news for simplifying legal language. If the difficult linguistic structures in legal language are there to highlight the performative nature of the text, we should be able to choose a new linguistic feature as a marker.

And maybe this time it will be one that works alongside plain English to help people understand legal obligations.

Francis Mollica does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.