Democracy indices compiled by respected organisations have suggested that around the world, there’s an increase in authoritarianism or democratic backsliding.

These indices typically draw from expert evaluations. They seldom consider the opinions of citizens in the countries concerned. So they may miss important parts of the democratic story.

One way to evaluate potential democratic backsliding is to examine nationally representative public opinion data. We’ve done so for three west African countries that have yet to hold elections in 2023: Sierra Leone (June), Liberia (October) and Togo (December).

Drawing on recently collected data from Afrobarometer, a non-partisan research network, we identified four themes prevalent in citizens’ attitudes about the democratic process. First, most citizens favour elections over alternative ways to select leaders. Second, they see their previous election as having been flawed. Third, citizens expect elections to feature violence. And fourth, they want candidates to focus on making the country better.

Afrobarometer conducts public attitude surveys on democracy, governance, the economy and society through nationally representative face-to-face interviews with 1,200 citizens in almost 40 African countries. For this analysis, we relied on the most recent results from 2022 (Togo in March; Sierra Leone in June-July; Liberia in August-September). We also used data going back to 2008 when describing longitudinal trends.

Demand for elections

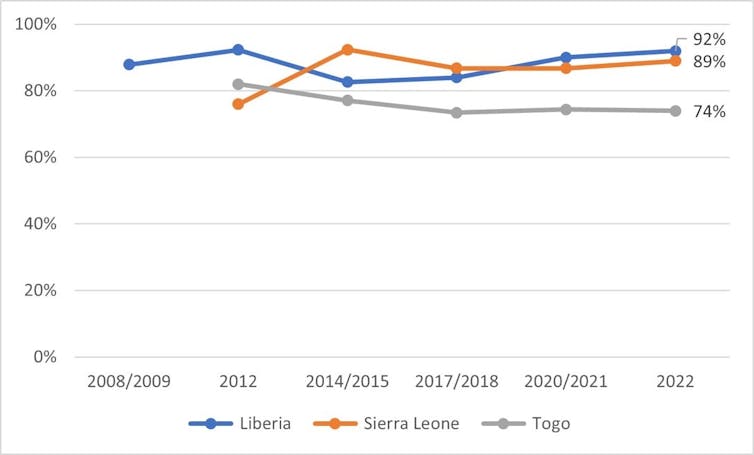

First, a large majority of citizens in all three countries agreed that their national leaders should be chosen through regular, honest and open elections (see figure 1). Around 9 in 10 Liberians (92%) and Sierra Leoneans (89%) agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, while around 3 in 4 Togolese did.

A rather small minority preferred a non-democratic alternative. Indeed, Liberia and Sierra Leone valued elections more than most other Africans. Togolese were close to the continental average compared to 31 other African countries surveyed by Afrobarometer.

Strong popular support for democratic institutions and processes is a key condition that many scholars have highlighted as a bulwark against a country developing a more authoritarian political culture.

Free and fair elections

Second, a minority of citizens believed the last national elections in their country had been fraught with major problems or had been entirely unfree and unfair.

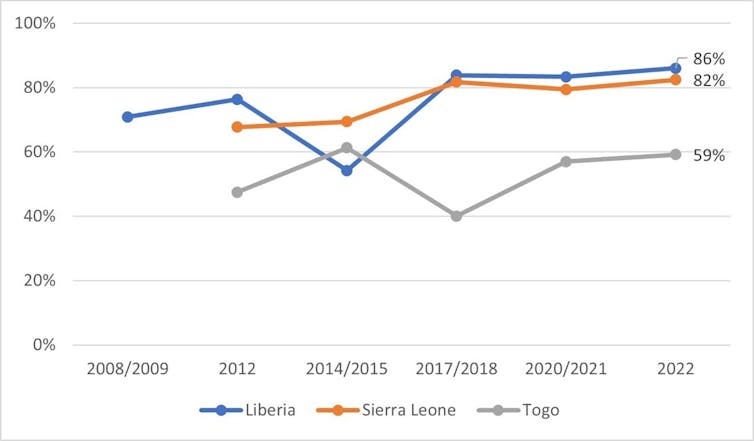

There was, however, variation across these countries. As the table below shows, Liberia’s and Sierra Leone’s citizens reported fairly positive perceptions of their last national elections. Most (86% and 82%) said that the most recent elections had been free and fair or only had minor problems, respectively. Only 59% of Togolese said the same. The improvement over time in Liberia, and the comparatively low position of Togo, both offer key lessons for democratic consolidation.

In Liberia, the newfound trust in electoral quality is likely due to former footballer George Weah’s victory in the 2017 elections, ending 12 years of United Party rule by garnering 63% of the vote.

More importantly, Weah’s triumph brought about the country’s first peaceful transfer of power since 1944. This is a second important condition that scholars frequently identify as crucial to democratic endurance.

The more negative perceptions among the Togolese may pick up on disillusionment with the continued rule of the Gnassingbé dynasty. (The father and son have been in office since 1967.) And the 2015 contest was flawed. The opposition challenger labelled it a “crime against national sovereignty”.

Opposition parties and figures regularly decry the institutional advantages of the ruling party, such as drawing electoral district boundaries in a way that favours itself, and the lack of presidential term limits. Opposition efforts at electoral reform have been dismissed and met with state-sanctioned repression.

Togo’s poor institutional design likely handicaps the opposition before any ballots are cast. This may be contributing to its citizens’ more negative evaluations of the electoral quality.

These institutional barriers figured prominently in the country’s major opposition parties’ decisions to boycott the 2018 legislative elections.

Electoral violence

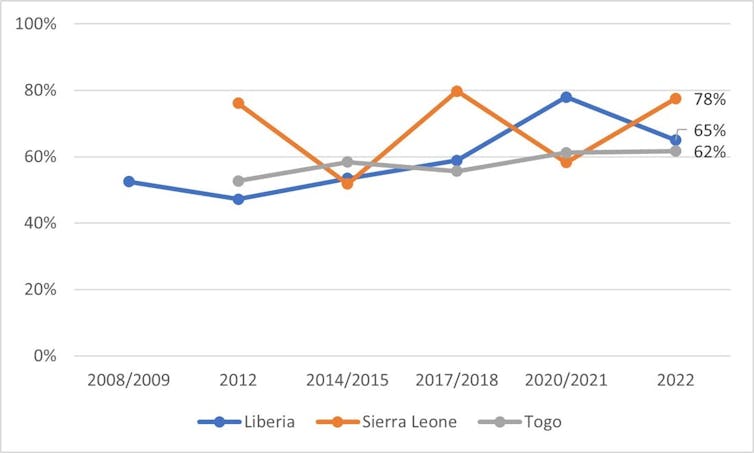

Third, and perhaps most worrying, is that a majority of survey respondents in three of the four west African countries believed that multiparty electoral competition led to violence often or always.

Some of these countries have a history of political violence. Togo erupted into violence with scores of deaths around its 2005 elections. Sierra Leone experienced an increase in political violence in the 2010s.

What should worry election observers, civil society actors and democratisation scholars is that rather than blaming government’s use of force, citizens appear to view multiparty competition as the cause of violence.

Solutions for citizens’ most pressing issues

Fourth, citizens in these countries said they would evaluate governing parties on their ability to provide solutions to the countries’ most pressing problems.

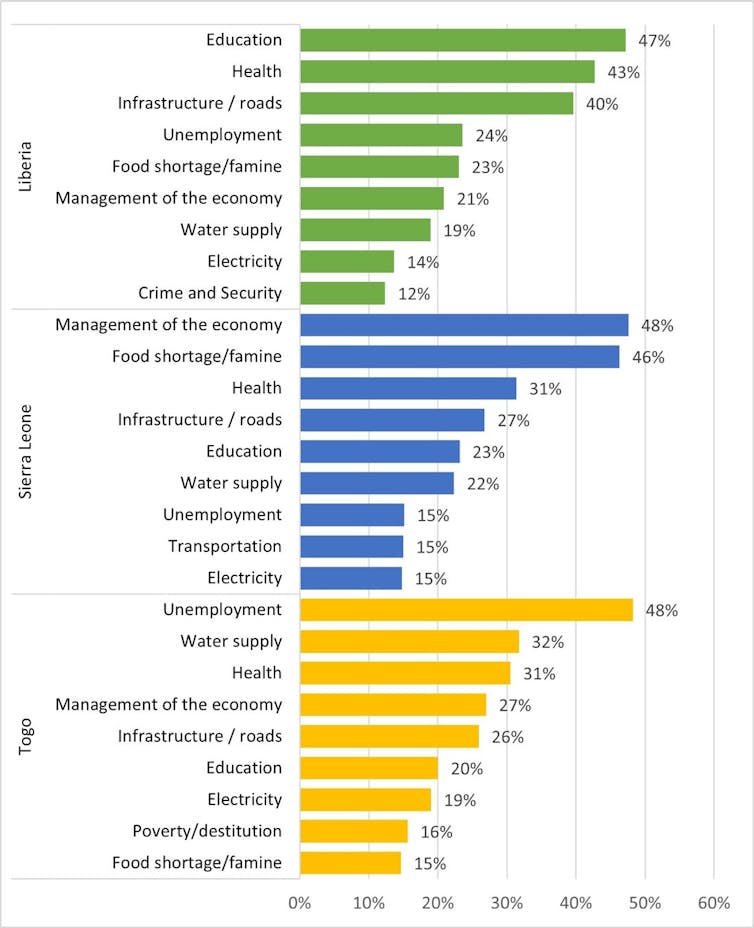

The figure below illustrates that routine concerns like economic management, the supply of public goods and infrastructural quality weigh heavily on citizens’ minds.

Politics in these countries has largely been free of the divisive appeals along ethnic or religious lines that have resulted in violence elsewhere on the continent. So presidential incumbents running for reelection in Sierra Leone and Liberia will have to take responsibility for their nations’ successes and failures. These issues are likely to feature heavily on the campaign trails in the coming months.

For the democratic optimist, these public opinion surveys offer hope. In these countries, citizens are likely to base their voting decisions on their living conditions. They will consider whether their basic needs are being met, and will appraise ruling parties’ economic management. This reflects democratic mechanisms at work, rewarding or punishing incumbents for their performance.

Several concerns for democracy’s consolidation remain, however. Perhaps most troubling for the prospects of democratic competition, a majority of citizens fear outbreaks of electoral violence. This raises the stakes for ordinary citizens to cast their vote.

What happens between now and the elections will likely determine outcomes like voter turnout, voter decisions and whether violence engulfs these countries.

Institutional reforms, whether before or after the elections, would go some way to enshrine democracy in these countries. But it would require a political change of heart by those who are likely to benefit from the uneven playing field in the short run.

Matthias Krönke works for Afrobarometer.

Thomas Isbell works for Afrobarometer.

Robert Nyenhuis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.