The mass killings of Iraqis started on the night of March 19 2003 with the US-led coalition’s “shock and awe” bombing of Baghdad. They called it “Operation Iraqi Freedom”.

Millions around the world sat transfixed in front of their TV screens, watching as bombs and missiles exploded. The reports came with the warning that they “contained flashing images”. True enough, the sky over Baghdad flashed orange and golden – but those were bombs, not flash photography.

The narrative of terror which began that day was to last for years. Terror from the sky, terror on the ground, terror from the foreign soldier, terror from one’s neighbour. By the time the invasion was completed, some 7,500 Iraqi civilians had been killed in the air strikes.

Each death was recorded by the Iraq Body Count (IBC) database, with which I have been involved for some years. Among them were 15 adults and children who lost their lives in Baghdad’s Zafaraniya area on March 30 2003:

As the war began, the US president George W Bush vowed to “disarm Iraq and to free its people” in a live television address, shortly after explosions had rocked the Iraqi capital. US military sources told the BBC that five key members of the Iraqi regime, including its president Saddam Hussein, were targeted in these first attacks – but that it was not known whether the targets had been hit and what damage might have been caused.

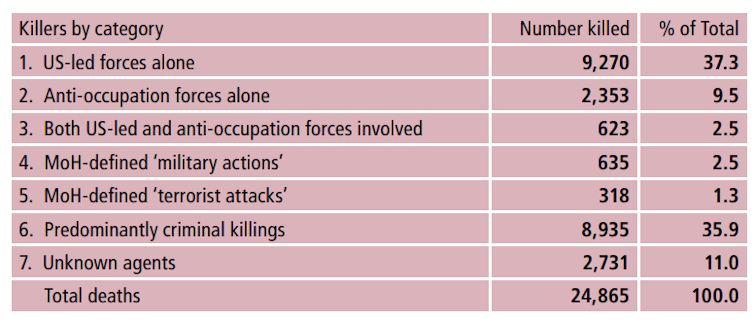

When it came to civilian deaths, an IBC dossier revealed the extent of the killings between 2003 and 2005. During the invasion and in the two years that followed, 24,865 civilians were reported killed – almost half in the capital Baghdad.

Nearly one-third of these civilian deaths occurred during the invasion phase before May 1 2003, when Bush made his “mission accomplished” speech from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, at the safe distance of the coast of San Diego.

US-led forces killed 37% of all civilian victims in the first two years. Anti-occupation forces and insurgents killed 9%, post-invasion criminal violence accounted for 36% of all deaths, and the remainder were killed by “unknown agents”. At least a further 42,500 civilians were reported wounded.

While mortuary officials and medics were the most frequently cited witnesses of these deaths, three press agencies (Associated Press, Agence France Presse and Reuters) between them provided more than one-third of all media reports.

The aftermath

Thousands of civilians have been killed each year since that first night of shock and awe. At its peak, in 2006, the conflict claimed 29,027 people. At its calmest, in 2022, there were 740 deaths.

Two decades on, the killings continue. IBC’s 2022 security report, Iraq’s Residual War, revealed that the country is still effectively at war.

In 2022, in addition to civilian killings, 521 Islamic State fighters were killed by the Iraqi military in joint operations with the US, and 506 members of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) were killed by the Turkish military. Other conflict-related deaths included 97 Turkish and 80 Iraqi soldiers, 30 members of the Popular Mobilization Forces (paramilitaries with links to Iran), and 23 federal police.

Pro-Iran parties dominate Iraq’s parliament, and more than 150,000 fighters of the former Iran-backed Hashd al-Shaabi paramilitary forces have been integrated into the state military.

In 2021, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights published a study that highlighted the severe and enduring injustices of the Iraqi justice system – based on 235 interviews with current or former detainees, as well as discussions with prison staff, judges, lawyers, families of the detainees and other relevant parties. As reported in the Washington Post, the study detailed:

… a labyrinth of unfairness, with detainees often denied due process at every turn … Confessions frequently come through torture … [such that] detainees frequently end up signing documents admitting crimes they did not commit. Few detainees see a lawyer until they appear in court. Methods of abuse include severe beatings, some on the soles of the feet, as well as electric shocks, stress positions and suffocation. Sexual violence was also reported.

There were also 1,352 arrests in Iraq in 2022 under the Terrorism Act. All these men face the death penalty.

Traumatised country

Since the 2003 invasion, Iraqis have been subjected to genocide, terrorism, the killing of protesters, poverty and the displacement of millions of people. When the war in Iraq officially ended in 2011 with then-US president Barack Obama declaring the withdrawal of troops, a deeply traumatised country was left behind, with a bankrupt economy.

Economists say that, due to falling oil prices and the effects of COVID on the country’s economy, Iraq’s poverty rate may have shot up from 20% in 2018 to more than 30% in 2020, meaning that 12 million Iraqis were living below the poverty line. In 2019, the estimated youth unemployment rate in Iraq was 25% – in a country where almost 60% of the population is under 25.

The future

In July 2016, in his report to the UK’s parliamentary inquiry into the Iraq war, Sir John Chilcot underlined the need for documenting the effects of military action on civilians. It was the government’s responsibility, he stated, to identify and understand the likely and actual effects of its military action. Referring to the war, he wrote:

Greater efforts should have been made in the post-conflict period to determine the number of civilian casualties and the broader effects of military operations on civilians. More time was devoted to the question of which department should have responsibility for the issue of civilian casualties than it was to efforts to determine the actual number.

One of Chilcot’s recommendations was that the UK government should be ready to work with others, in particular NGOs and academic institutions, to develop such assessments and estimates over time. The vast majority of civilian deaths in Iraq remain only partially documented. A respectful and humane account of all the Iraq war’s dead remains an unfinished task.

Lily Hamourtziadou does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.jpg?w=600)