Invasive species – including plants, animals and fish – cause heavy damage to crops, wildlife and human health worldwide. Some prey on native species; other out-compete them for space and food or spread disease. A new United Nations report estimates the losses generated by invasives at more than US$423 billion yearly and shows that these damages have at least quadrupled in every decade since 1970.

Humans regularly move animals, plants and other living species from their home areas to new locations, either accidentally or on purpose. For example, they may import plants from faraway locations to raise as crops or bring in a nonnative animal to prey on a local pest. Other invasives hitch rides in cargo or ships’ ballast water.

When a species that is not native to a particular area becomes established there, reproducing quickly and causing harm, it has become invasive. These recent articles from The Conversation describe how several invasive species are causing economic and ecological harm across the U.S. They also explain steps that people can take to avoid contributing to this urgent global problem.

1. The best intentions: Callery pear trees

Many invasive species were introduced to new locations because people thought they would be useful. One example that’s widely visible across the U.S. Northeast, Midwest and South is the Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana), a flowering tree that botanists brought to the U.S. from Asia more than 100 years ago.

Horticulturists loved the Callery pear for landscaping and wanted to produce trees that all grew and bloomed in the same way. As University of Dayton plant ecologist Ryan W. McEwan explained, they created identical clones from cuttings of trees with the desired characteristics – a process called grafting. Unlike some trees, a Callery pear can’t fertilize its flowers with its own pollen, so plant experts thought it wouldn’t spread.

However, “as horticulturalists tinkered with Callery pears to produce new versions, they made the individuals different enough to escape the fertilization barrier,” McEwan wrote. As wind and birds spread the trees’ seeds, wild populations of the trees became established and started crowding out native species.

Today, Callery pear trees are such scourges that several states have banned them. Others are paying residents to cut them down and replace them with native plants.

2. Tiny organisms, big impacts: Zebra and quagga mussels

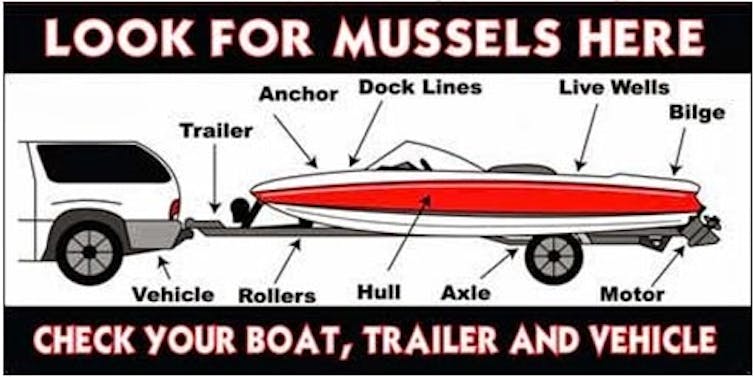

Invasive species don’t have to be large to cause outsized damage. Zebra and quagga mussels – shellfish the size of a fingernail – invaded the Great Lakes in the 1980s, clogging water intake pipes and out-competing native mollusks for food. Now they’re spreading west via rivers, lakes and bays, threatening waters all the way to the Pacific coast and Alaska.

As Rochester Institute of Technology environmental historian Christine Keiner wrote, it took several decades for the U.S. and Canada to regulate ships’ management of their ballast water tanks, which was the route by which the mussels were introduced to North America.

“Now, however, other human activities are increasingly contributing to harmful freshwater introductions – and with shipping regulated, the main culprits are thousands of private boaters and anglers,” Keller wrote. Limiting the destructive impacts of invasive species “requires scientific, technological and historical knowledge, political will and skill to persuade the public that everyone is part of the solution.”

Read more: The westward spread of zebra and quagga mussels shows how tiny invaders can cause big problems

3. Threatening entire ecosystems: Lionfish

When an invasive species is especially successful at spreading and reproducing, it can threaten the health of entire ecosystems. Consider the Pacific red lionfish (Pterois volitans), which has spread throughout the Caribbean and now is moving south along Brazil’s coast.

Lionfish thrive in many ocean habitats, from coastal mangrove forests to deepwater reefs, and they prey on numerous smaller fish species. In the Caribbean, they have reduced the number of small juvenile fish on reefs by up to 80% within as little as five weeks.

“Scientists and environmental managers widely agree that the lionfish invasion in Brazil is a potential ecological disaster,” warned Brazilian marine ecologist Osmar J. Luiz of Charles Darwin University. “Brazil’s northeast coast, with its rich artisanal fishing activity, stands on the front line of this invasive threat.”

Although the Brazilian government was slow to address the lionfish threat, Luiz asserted that “with strategic, swift action and international collaboration, it can mitigate the impacts of this invasive species and safeguard its marine ecosystems.” That will require many techniques, from recruiting coastal residents to monitor for the invaders to tracking lionfish subpopulations using DNA analysis.

4. The value of acting locally

Public awareness is critical for stemming the spread of many invasive plants and animals. That can involve actions as simple as cleaning your shoes and socks after a hike.

“Certain species of nonnative invasive plants produce seeds designed to attach to unsuspecting animals or people. Once affixed, these sticky seeds can be carried long distances before they fall off in new environments,” explains Boise State University ecology Ph.D. candidate Megan Dolman.

Research shows that recreational trails promote the introduction of invasive plant species into natural and protected areas, including national parks and scenic trails.

In her research, Dolman found that few Appalachian Trail hikers were aware of the risk of carrying invasive plant seeds on their shoes or socks, so they typically did not take steps such as cleaning their gear before and after hiking. By knowing about invasive species in their areas and ways to manage them, people can help protect special places and keep invasive species from spreading.

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.