The best bike rides, for me, are the ones that you aren’t quite certain of finishing. Your fate is unknown. Getting to the end, if it ever comes, will require a liberal quota of physical and psychological distress. You will sweat, you will toil, you will swear, you might even scream. Finally, after rage, rage raging against the dying of the (day)light, the finishing line miraculously hoves into view. Cue an unrivalled sense of accomplishment, the satisfaction of a job tremendously well done. Well, that’s the best-case scenario anyway – and it’s what I was hoping for when, in mid-April, I set the controls for North Wales.

Cycling UK’s latest off-road challenge, the Traws Eryri (pronounced trouse eh-ruh- ree) – or Trans- Snowdonia, in English – was my first ‘I might not actually complete this’ ride of the year. Firstly, it takes place on unforgiving Snowdonian terrain; secondly, it’s 125 miles long with 4,000 metres of vertical gain; and thirdly (and perhaps most crucially) I’d be tackling what is essentially billed as a mountain bike ride on a gravel bike. Why? Well, quite.

Why is a question that, while not necessarily keeping me awake at night, has been playing on my mind since gravel bikes first found their way over to the UK from across the pond. What exactly are these bicycles for? They aren’t quite road bikes, they aren’t quite mountain bikes. They bear passing resemblance to cyclo-cross bikes – but good heavens, they most definitely aren’t. Surely these mutant machines haven’t been manufactured solely for the purpose of being ridden exclusively on gravel because, if that were the case, I’d be paying out three-odd grand to do lengths of my neighbour’s driveway. In taking on the Traws Eryri I’d be putting a gravel bike – Giant’s Revolt X Advanced Pro – to the test and finding out how capable they actually are.

I used a Giant Revolt X (£5,499, reviewed CW 23 May) with all the necessary accoutrements: a dropper post, RockShox Ruby front fork with 40mm travel and flip-chip for geometry adjustments feature on this top-end model to make it as accommodating of the widest range of terrain possible. A carbon- fibre frame boasts bottle cage and luggage bosses aplenty, and the SRAM eTap gearing makes for smooth changes, even when putting down power on technical ascents. This model came with 42mm tyres with room for 50s.

Given the hugely diverse terrain, there is no perfect bike for this ride. In certain sections you’d gain time on a fully rigid gravel bike with 28mm tyres, while in other parts you wish you were on a full-suspension mtb with 200mm of rear travel. The Giant had a pretty damn good go at everything that was put before it – and I’m actually convinced that this type of bike is the best for the Traws-Eryri. I’ve also since ridden 100 miles on the South Downs Way on this bike, having previously used hardtail mountain bikes and rigid gravel steeds, and can confirm that this type of bike will be my go-to for future endeavours on the Downs.

Mauled by Moelfre

I started the route from the north in the walled market town of Conwy in North Wales. The sun shone as I threaded my way from the castle and through the clamouring streets of the tourist-filled town. The air was imbued with a brackish quality from the Irish Sea and for five minutes it almost felt like I was on holiday in Majorca – the 42mm tyres of my Giant Revolt X buzzing pleasingly along smooth asphalt streets. Then I came to the first off-road section and it no longer felt like I was on holiday in Majorca. It felt more like I’d cycled into a reenactment of the Battle of the Bulge.

Steep singletrack booby trapped with thick, lumber- like roots was the new normal as I engaged my 52-tooth sprocket and winched my way to what I’d hoped was the top. But this was not the top. It was still very much the bottom. Riding out of a channel of dense vegetation, I now had a clear view of what was to come – it stared back at me and my gravel bike and, if landscapes could laugh, that’s what it would have done. Yes, all 589 metres of Moelfre, the first mountain of the day, and the third-highest point on the route, sneered at us to ‘come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough’. So we did. And we weren’t.

It was around a third of the way up, just after I’d taken an impromptu bath in an inconsiderately located mountain stream, that I began to question not so much whether I’d be better off on a mountain bike for this journey, but something with a touch more oomph, like a tank. To give you a little perspective, in the first two hours of this ride – the time it took to summit and descend Moelfre – I had covered 10 miles. My great auntie Jean could walk faster than that, and she’s been dead for 10 years.

Yes, this was a baptism of fire, and yes, it made me want to repair to the nearest bicycle – echoed through the valleys, fast- running rivers adding a touch of treble to the rolling baseline of the bike. Nothing else could be heard. This was a cycling paradise – the simple act of turning pedals in this landscape was the source of much joy, it made me very happy. But on rides of such length, feelings of joy and complacency are usually punished; there’s always the potential for things to go wrong. Indeed, just as I was congratulating myself for being so amazing, it started to rain. Not only that but the wind started breaching the business end of the Beaufort Scale. Hero to zero at the behest of Mother Nature.

As it likes to do in Wales, the rain set in. It wasn’t coming down in lashing horizontal sheets, but that steady fine stuff that likes to hang around – the stuff that unscrupulously soaks you down to the most intimate reaches of your chamois leather. That stuff. I stopped in Betws-y-Coed for a meal deal – surely that would make things better. Enjoying the ultra-processed flavours of a bag of Beef Monster Munch, I took in my surroundings. Mountain bikers. Everywhere. Of course there were, this was North Wales after all, the birthplace of trail centres in the UK – full-face helmets and body armour appeared flavour of the day here. But the road before me, although rocky, was perfectly manageable on the gravel bike.

Getting There

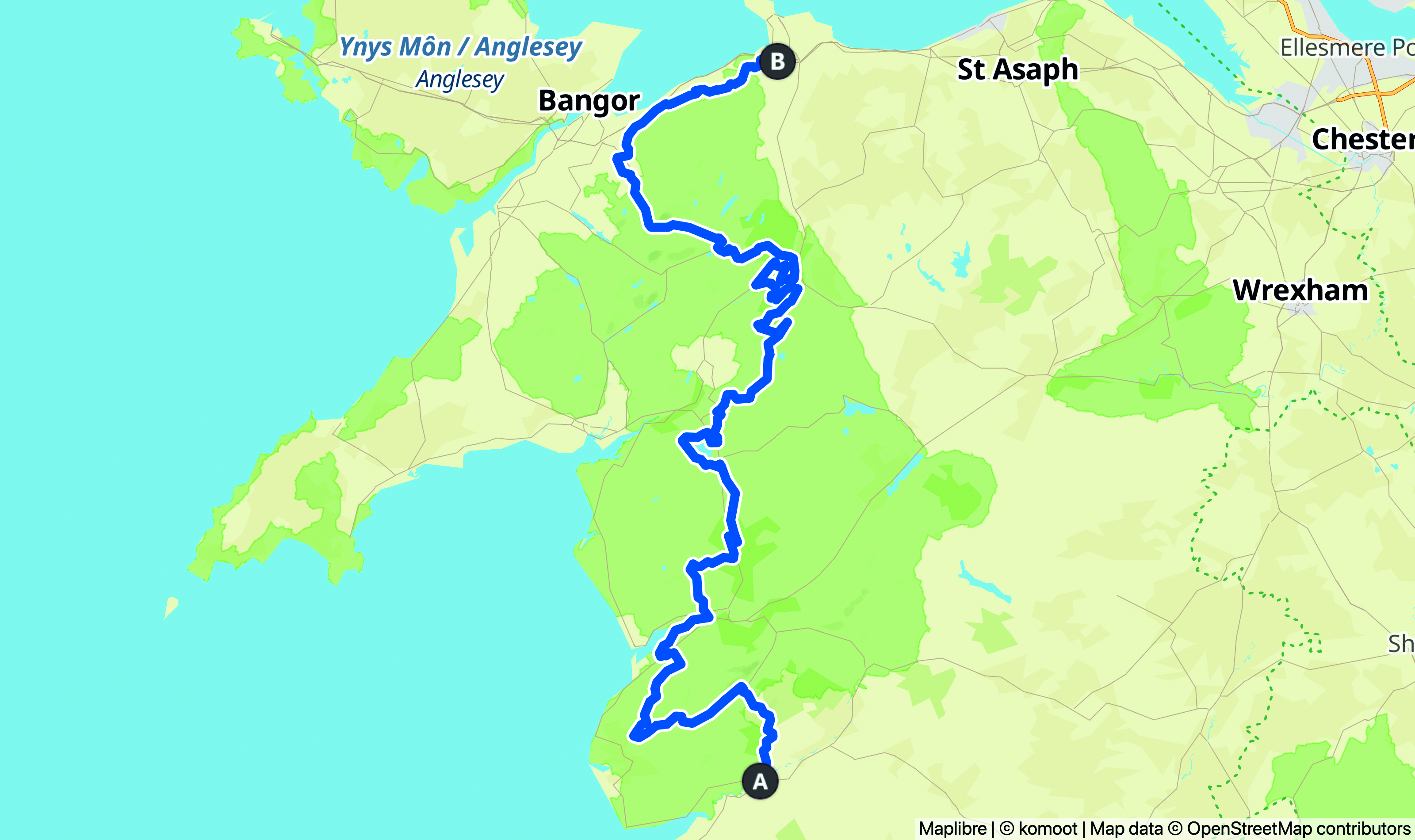

Where you start and finish is up to you. I started in Conwy, situated at the north of the mountain range, finishing in Machynlleth to the south. Both are served by train stations and are easily accessible by car if you’d prefer.

Where To Stay

The Hilton Garden Inn near Conwy was a great place to get some shuteye before the start of the trip. Rooms are well provisioned, clean and comfortable at £125 per night with breakfast. A bar and restaurant area downstairs off ers the option for pre- ride fuelling or post-ride replenishment. www.hgisnowdonia.com

The Wynnstay Hotel in the centre of Machynlleth is metres away from the start/fi nish point. The rooms have baths and the meals were exceptional. £125 B&B. www.wynnstay.wales

Where To Eat

As mentioned, in Machynlleth it’s hard to recommend anything past the Wynnstay, as the food was truly sublime. There’s a handful of eateries scattered throughout the town, including the Hermit Crab Cafe for good cake and coffee.

Twenty miles of undulations on a variety of terrain eventually deposited me close to the top of Glasgwm, a 780-metre mountain. With around half the route down and some 2,000 metres of ascent in the bag, this was a definite landmark. The bike had behaved perfectly up to now: no punctures, and the 40mm of travel provided by the RockShox Rudy front fork had afforded me the chance to descend with confidence, albeit without threatening the top 10 of any Strava leaderboards.

After unskillfully negotiating a slippery section of singletrack from which I emerged sporting a liberal layer of sheep excrement, one of the few flat bits of the route presented itself, in the shape of Trawsfynydd. Featuring a decommissioned nuclear power station on the bank of a 5km-square reservoir, Trawsfynydd gave me an atomic kick up the ass. Although the drizzle had already infiltrated every square inch of my clothing, I felt buoyed by the break in undulations, reached for the drops and tapped out some much-needed mileage.

The route’s second mountain bike trail centre, Coed-y-Brenin, saw me take a brief but terrifying detour onto some red-graded singletrack that emphatically answered the question about how well I rail berms. Badly. Gnarly chutes of evil aside, the technicalities of the Traws Eryri had so far comprised boggy singletrack and slippery rock gardens that would bring about a certain amount of falling off regardless of the steed. Thankfully, gravel bikes are considerably lighter than most mountain bikes, so shouldering the Revolt was an easy decision to make when faced with these obstacles. Never once did I wish I was on any other kind of bicycle.

Before we started congratulating ourselves on winning the war, however, the final battle had yet to be waged. A huge great hunk of mountain lay in between us and the finishing point in Machynlleth. And this one was not for the faint of heart. I rumbled over rustic cattle tracks for what felt like, well, time just stopped – it was the very definition of a purgatorial ascent. The brow, though you could see it, glistening, even in the midst of the most ashen Snowdonian sky, remained elusive. The long and winding path teased with the hint of a summit before abruptly adding a sharp right here, a meandering left there, until the whole mountainside had been well and truly ridden.

Have bike, will gravel

My pace had dwindled, my cadence barely registering 30rpm, turning the 52-tooth chainring as though it were a millstone. Each pedal stroke, owing to the technicality of the ascent, served to further tenderise my quads. I yearned for blacktop, preferably with a descending trajectory and ending at some sort of cafe. Pedalling had become so utterly predictable. But an hour after I’d embarked on this climb, it was as if the Traws Eryri-an gods had heard me – for, after being treated to beautiful views of the Barmouth coastline, I found myself flying down the other side of the mountain on what was surely the smoothest tarmac in Wales, for about five miles – parting herds of sheep as I rode like some kind of gravel-biking prophet.

This had been, in my opinion, a breakthrough journey for the gravel bike, and more than a small step for man. So what exactly are these bikes for? Quite simply, off-road endurance. This is a riding discipline that’s gaining exponential amounts of traction (pun intended), with long- and ultra-distance multi-terrain events becoming ever more popular. You can’t shred singletrack on a gravel bike, and you’re unlikely to be setting KOMs on the road, but who cares? What you have here is a jack of all trades and a perfect tool on which to explore the path less travelled. Rolling through a succession of small villages, the signs to Machynlleth were impossible to miss, and before long I was in a pub, celebrating my first big ride of the year with a pint of Purple Moose. Iechyd da!