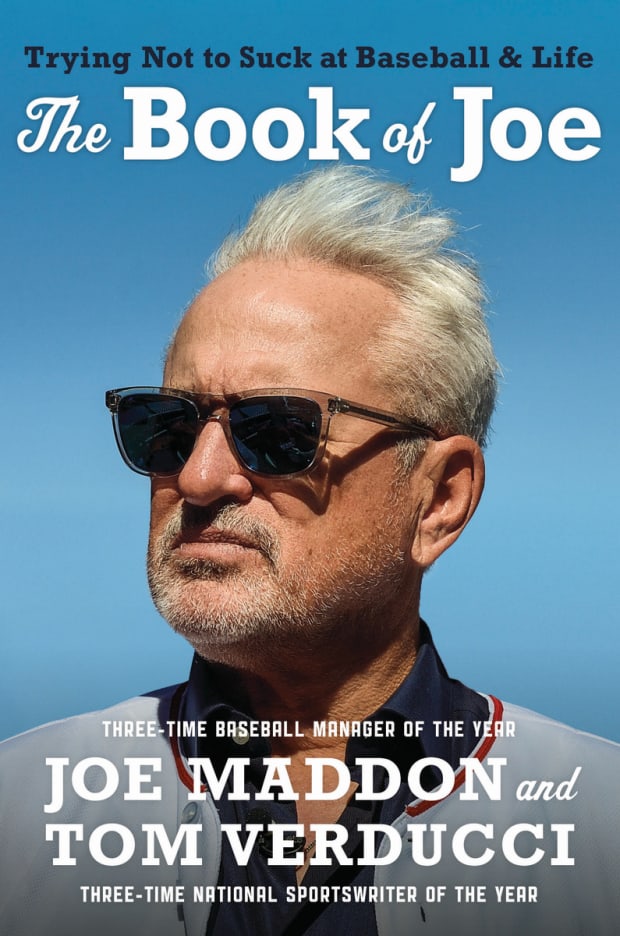

Excerpted from THE BOOK OF JOE: Trying Not to Suck at Baseball & Life by Joe Maddon and Tom Verducci. Copyright © 2022 by Joe Maddon and Tom Verducci. Reprinted by permission of Twelve, an imprint of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Billy Martin was fired nine times. The first time he was dismissed, in 1969 by the Twins, he was fired by appointment. One Sunday night shortly after the season, the brother of Minnesota president Calvin Griffith told Martin to expect a call from Griffith at precisely 10:30 the next morning. Martin deduced his boss was not arranging the call to extend his contract. He was correct.

Yogi Berra was fired by proxy in 1985. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner sent general manager Clyde King to fire Berra after a win in Chicago, just 16 games into a season in which Steinbrenner vowed Berra would manage the full year. So upset was Berra about being fired through an intermediary that he did not set foot in Yankee Stadium or speak to Steinbrenner for the next 14 years.

The Phillies fired Gene Mauch by telephone in 1965 after he had flown from Philadelphia to Los Angeles to attend to his wife, who was hospitalized with a stomach ailment. Asked when it dawned on him that he might be fired, Mauch snapped, “Eight years and two months ago.” That’s when Philadelphia had hired him.

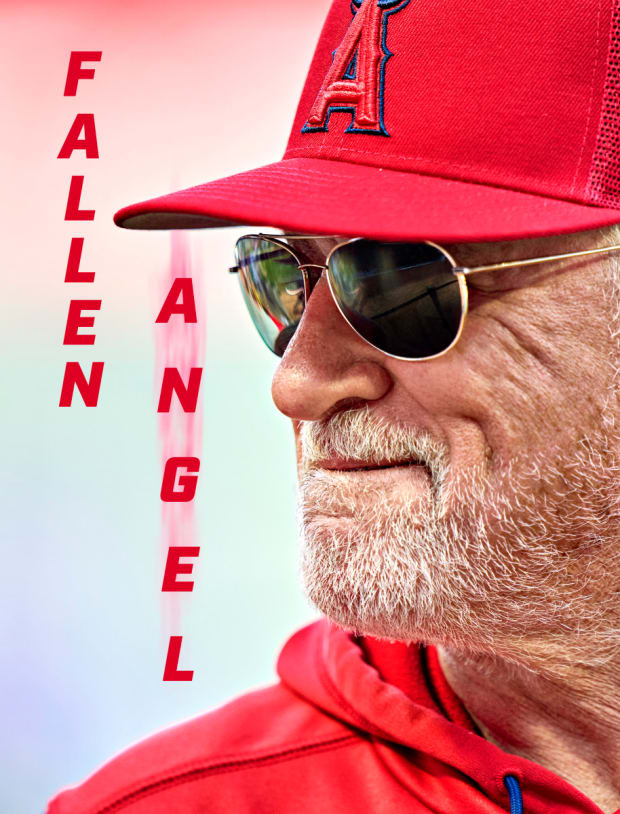

Joe Maddon was fired in his living room, sporting a freshly cut mohawk. On the morning of June 7, 2022, the Angels had lost 12 games in a row in a cavalcade of oddities and disasters, including the worst two weeks of Mike Trout’s baseball life (he hit .114 and struck out 17 times in those 12 games); a slump by Shohei Ohtani (.180, 15 strikeouts); injuries to key hitters Anthony Rendon and Taylor Ward; and epic failures by the bullpen. Los Angeles held 10 leads in those dozen games and lost them all.

Maddon had figured it was time to pull a page from an old playbook. On Sept. 15, 2008, the Red Sox had pummeled his Rays, 13–5, to create a virtual tie atop the American League East between the two teams. It was the first time in 52 days Tampa Bay did not hold the outright lead. The Rays were fading, and so was the amazing story of their rise from the worst record in baseball one year to the playoffs the next.

Maddon showed up at Tropicana Field the next day with a mohawk, a bold move if only because he and his fiancé, Jaye, were to be married the following month. Jaye had reminded him that wedding portraits last forever. Vanity be damned, Maddon figured the haircut was a good way to loosen his team in the heat of the pennant race. Earlier that month, Rays center fielder B.J. Upton had sported a mohawk. The sight of their manager also rocking the ’do raised the silliness factor. Soon other players—and it seemed half the Rays’ fans—had mohawks.

The night of the Maddon Mohawk, the Rays won 2–1. They won the next night, 10–3. And they won six of their next eight games to pull away from the Red Sox and win the division by two games.

In 2022, though, Maddon never made it to the ballpark with his mohawk. Angels GM Perry Minasian arrived at Maddon’s front door and rang the bell. Maddon answered and invited him in. Minasian did not immediately notice the mohawk. If he did, he said nothing about it. He appeared uncomfortable.

Maddon thought he had a good idea of why Minasian was there. Over the previous few days Minasian had told Maddon he was considering firing some coaches. “You can’t do that,” Maddon had told him. “They’re very good at what they do. No, that’s not the answer.”

John Cordes/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Maddon took Minasian’s appearance on his doorstep as a bad sign for his coaches. They sat down in the living room. Minasian made a quick comment about Maddon getting “a haircut.” The words lacked the lilt of humor. Quickly it was apparent why. Minasian said he was “making a change” and removing him as manager. “I’ve got to do something, Joe,” Minasian told him.

Says Maddon, “I did not overreact at all. I just said, ‘O.K.’ Quite frankly, I was happy he chose me and not the coaches. No one on that staff deserved to be fired.

“What was needed at that juncture was support . . . and not another version of the blame game. We all needed support from the bosses. That includes ownership. It would have been very easy for Arte Moreno to get on an airplane, walk through the clubhouse, talk to us, see what was going on, and I believe he would have come to a different conclusion.”

Maddon and Moreno, the Angels’ owner, had known one another for two decades. During spring training Joe and Jaye had hosted a party at their Arizona home for the entire staff and their spouses. Moreno and his wife, Carole, attended. Moreno did not speak to Maddon after the firing.

Maddon’s firing had not been Moreno’s idea, anyway. It was Minasian’s. The GM spoke with Moreno just that morning and told the owner what he had in mind. “If this is what you decide is needed to right the ship, go ahead,” Moreno told him, according to a team source familiar with the conversation. “It’s totally your call.”

The firing was not about Maddon losing the clubhouse; Minasian later said he did not consult with any players or coaches about the change. It was not about effort; Minasian said at his news conference later that day “the effort has been great.” He did not give Maddon any specific reasons for why he was firing him. He kept telling him, “I’ve got to do something.” Nor did Minasian provide specificity at his news conference.

Why, then, was Maddon fired? Before the losing streak, only the Yankees and Astros had won more games than the Angels in the American League. The team was improving under Maddon in his third year, just as it had in his second year, just as his teams did in his previous managing jobs with the Rays and Cubs. How could a World Series–winning manager with 19 years and 2,599 games of experience lose his job over a 12-game sample?

The answer is that the firing had been in the works long before those dozen games, even if both men could not or did not want to see it that way. The losing streak simply provided an exit ramp for a relationship that was going nowhere—not because of any personal animosity but because of philosophical differences.

Kirby Lee/USA TODAY Sports

What happened between Minasian and Maddon tells a familiar story of what has happened to the role of the manager—and baseball itself. The power shift from the dugout to the front office over more than a quarter of a century has changed how the game is played, and its value system. Knowledge over wisdom. Technology over teaching. Data over art. Efficiency over entertainment.

As front offices seized control, games grew longer, with less action, and there were more pitching changes, more fungibility of personnel and fewer fans. (Attendance has declined slowly but steadily since the all-time per-game high in 2007.) Meanwhile, baseball managers ceased being celebrities. It happened in part because the replay challenge system reduced colorful arguments with umpires, but mostly because managers operated with less power and job security than general managers. To survive, they adopted the bland corporate-speak of their bosses.

The shift happened over the arc of Maddon’s career in the major leagues. He was trying to hold on to the soul of baseball as he knew it, relying on trust, relationships and his coaches. Minasian was part of a generation of power brokers who dove even deeper into data and process. Depending on how you were raised in the game, a 68-year-old man in a mohawk was either a colorful master motivator or an unfunny gimmick that had no bearing on the win probability of the game that night.

If there was a physical space where this dynamic played out it was the coaches’ room at Angel Stadium. Minasian and his top assistant, Alex Tamin, maintained lockers in the same room as the coaches, using the room as they changed between front-office attire and workout or game-day attire.

In the game in which Maddon was raised, GMs stayed out of the clubhouse unless they had specific business to attend there. The clubhouse and its immediate environs belonged to uniformed personnel. But Minasian and Tamin found it perfectly normal to share space with coaches on an everyday basis because it had become perfectly normal for executives to dictate game strategy as much as coaches. What Maddon regarded as interference Minasian regarded as standard operating procedure.

Maddon was also put off by some of the copycat processes implemented by Minasian. A certain intramural competition exists among baseball front offices, a kind of Silicon Valley cutting-edge war as to who can hire the smartest experts and install the latest technology, whether it’s $15,000 whole-body-vibration “power plates” for training or $24,000 air and surface purifiers that convert ambient oxygen and humidity into dry hydrogen peroxide to reduce the presence of microbes. Last season the Giants plowed new ground by employing 13 coaches—one for every two players—including three hitting coaches and three pitching coaches. That number does not include their “breathing coach.”

The Giants, Dodgers and Braves especially served as references for Minasian and his front office staff. In 2022 the GM instituted daily meetings with players, primarily the hitters, rather than just the traditional first-game-of-a-series meeting. “I just think it’s way too over the top,” Maddon says. “[Minasian] kept reminding me, ‘The Braves did it. The Braves did it.’ Fine. A lot of things were related to ‘We did it this way with the Braves,’ or ‘This is how the Giants did it.’ We were all over trying to do things like somebody else.”

After last season, Minasian replaced Maddon’s bench coach, Mike Gallego, with Ray Montgomery, a 52-year-old former player making the rare jump from the front office to the field. Montgomery, who had been the director of player personnel, was working in uniform for the first time after spending most of his career in scouting. Montgomery helped run those daily meetings.

Moreover, what Maddon calls a pregame “choreography” took root, spearheaded by Minasian and Tamin. Those two, not Maddon and his coaches, would decide which relief pitchers were not available for the game that night. It was based on a proprietary algorithm developed by Tamin that kept track of a pitcher’s work in rolling 30-day increments. In recent years it had become common for front offices to usurp control of the bullpen from managers. So-and-so “is down tonight” entered baseball parlance, and it came from upstairs. “In that losing stretch that led to my demise, a lot of relievers were made unavailable,” Maddon says. “I couldn’t use them.

“Tam had the 30-day matrix built on how to use relief pitchers, how often and how much rest they needed. Honestly, that’s insulting.”

Maddon read body language, mechanics, clues in how his players answered his questions . . . all the insights gleaned from 42 seasons in professional baseball. The modern front office, however, has too much access to data to rely on the instincts of a veteran manager. Minasian and Tamin were not revolutionaries. They were deploying methodologies that had become mainstream. Says Maddon, “If you’ve grown up in an era of understanding the game and how important it is beyond the numbers to connect with people and establish patience and relationships with your players in order to have success, it’s hard to get on the same page with front offices today.

“Other managers that I’ve spoken with, guys with experience, feel the same way, and they are encouraging me to speak up. This is not an attempt by me to ‘get even’ or anything like that. I’m not trying to protect myself. It’s exposure. If you’re a baseball fan, if you love the game and care about the game, you should know what is behind how the game is being played today.”

Buy THE BOOK OF JOE: Trying Not to Suck at Baseball & Life

The divide between old and new, manager and front office, data and art, Maddon and Minasian, reached a boiling point on May 9. The Angels had just scored five runs in the seventh inning against the Rays to turn a 6–3 lead into an 11–3 blowout. Ohtani hit a grand slam. The dugout was lively. Suddenly, head athletic trainer Mike Frostad walked up to Maddon at his usual perch on the top step of the dugout and said, “Perry just called down. He said get Trout out of the game.”

Earlier in the day Trout had complained about a bit of soreness in his groin. But later he told Maddon that the soreness dissipated, and he was fine.

To Maddon, Minasian broke a sacred code. The GM had called the dugout during a game to dictate strategy to the manager—a proven, veteran manager at that. To Minasian, he simply was deploying the power given to this generation of executives. Nothing was sacred. Nothing was out of bounds.

The next day Maddon blew up at Minasian in Maddon’s office. “Listen, don’t you ever f------ call down to the dugout again!” Maddon said.

Twenty-six days later, he was gone. When Minasian fired him, Maddon offered him advice. He suggested that Minasian not bring Tamin on road trips. He did not tell Minasian to leave the coaches’ room to the coaches. “I was going to text him the next day to bring it up, but I chose not to,” Maddon says. “It was over.”

Coaches and coaching are at the heart of Maddon’s baseball belief system. To him they are to baseball what teachers are to education. Underpaid and underappreciated but indispensable. Keepers of the flame. “Who is teaching the next generation of coaches, and what are they teaching?” Maddon asks. “Is the game being taught or is it more reliant on studying feedback from technology? The players want to hear more and more about exit velocity and spin rates from coaches, as opposed to mechanical information that only a well-trained pitching coach or hitting coach could pass along.

“Who is mentoring these groups? How is the game being passed on with the eradication of minor league teams? There is a lot of tearing of the fabric right now.”

At the top of today’s major league organizational chart is a triangle. The owner, lead baseball operations person (traditionally the GM, though title inflation has wrought fancier designations) and manager form the corners. But the triangle is inverted. The manager is at the bottom. The owner and general manager hold power over the manager, even as it relates to game strategy and coaching. The triangle works best only when all three positions buy in completely to the structure and philosophy.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

General managers increasingly prefer to hire managerial blank slates: candidates with little or no experience and thus no established philosophies or norms to clash with how they want the job done. In 32 managerial changes from the 2017–18 offseason through Maddon’s firing by the Angels, general managers picked a first-time manager on 19 occasions—almost 60% of the time.

The Angels’ inverted triangle lacked seamless philosophy and stability. Deep down, Minasian and Maddon knew this. Twelve straight losses forced Minasian to confront that reality. He replaced Maddon with Angels third-base coach Phil Nevin, another first-time MLB manager.

“The only reason you fire the manager,” Maddon says, “is there is a total disconnect between the manager and players, or there is a philosophical disconnect between the manager and either the GM or the owner. I plead guilty to having philosophical differences with Perry. You don’t take it personally. It’s business.”

Maddon wants to manage again. But baseball has changed since he was a rookie manager with the 2006 Devil Rays. If Maddon has a place in the game again, it will be for someone else who also honors the soul of the game, who believes data enhances and complements art and instinct, not depreciates them.

“Right now as a manager, you need to understand you are going to be controlled,” Maddon says. “You’re really going to be required or asked to do exactly what the front office wants you to do. The trick then would be to somehow be able to build relationships—but even then, your ability to freely think, work and suggest with these players can be constricted. It’s just the way of the world right now.”