At 22, Ellesse Andrews is already on track to becoming one of NZ's greatest cyclists. Suzanne McFadden discovers how a change of mind - and mentoring from one of Australia’s best - helped her to three Commonwealth golds.

Jon Andrews noticed the change in his daughter, Ellesse, about a month ago.

The first signs were in the city of Cali, Colombia, where she won her first World Cup medal, a bronze, as a solo sprinter; subtle differences that maybe only a parent or a coach might notice.

Then earlier this week, in front of his TV set at home in Christchurch, Andrews watched a little surprised as his 22-year-old daughter boldly stared down her far more experienced rivals on the start-line inside the Lee Valley velodrome in London.

It was a psychological shift – a new-found confidence in her ability to outsprint anyone she came up against.

A change that would help her win three Commonwealth Games gold medals in just four days.

“Her whole psychological approach to sprinting has just gone to an entirely new level in the last month,” says Jon Andrews, once a champion sprinter himself.

“A couple of the things she’s done recently, you could tell she was starting to make a big shift in the individual sprint. It’s been gradual but then, boom, it’s all come together at once.”

Ellesse Andrews’ precocious ability on a bike is nothing new. We saw her, incredulous and tearful, winning silver in the keirin at last year’s Tokyo Olympics. Before then, she’d been a junior world champion in both sprint and endurance events – an almost freakish achievement to be dominant in both power and speed.

Her old New Zealand cycling team-mate, Olympic medallist Ethan Mitchell, had witnessed the determined young woman’s dedication to training over the last few years – “some of the hardest work I’ve seen from anybody” – and had no doubt she had the physical ability to do it.

But it seems Andrews, who’s studying psychology away from the track, is now getting her head into the tactical game of sprinting - and thriving in it.

Things like the intense eyeballing she employed before out-gunning the Olympic sprint champion, Canadian Kelsey Mitchell, in two straight races on Sunday morning.

“We asked Ellesse about staring down people before a race, because that’s not really her normally,” says Jon Andrews, an Olympian and two-time Commonwealth Games medallist. “She said ‘You’ve got to watch them really carefully so they don’t get a jump on you. So why not just stare at them right from the very beginning?'

“She’s not trying to psych them out, she’s just watching them intensely.”

It’s pretty scary, says Ellesse’s mother, Angela Mote-Andrews, who’s been a top mountain biker and multi-sport racer: “But Jon and I are pretty intensely competitive too.”

Now that they think about it, they’d actually seen her attitude coming.

“When Ellesse was a little kid, if you had any secrets from her or wouldn’t tell her something, she would get really feisty, really cross, until you told her,” Jon Andrews says. “That determination is definitely part of her personality.”

Growing up in Wānaka, a 13-year-old Ellesse would try to outsprint her parents at the end of a family mountain bike ride, refusing to give up until she had.

While some of the key characteristics that make her a champion – competitiveness, desire and focus – are innate, she’s still learning new mental skills, says Jon, who coached her until she reached cycling’s elite level at 19 (all but four of the track team at these Games went through the Cycling NZ junior programme when he was involved).

The arrival of the new lead sprint coach at Cycling New Zealand, Nick Flyger, has had a major impact on Andrews.

Flyger, a Kiwi who grew up in Nelson, had been Australia’s senior track sprint coach for four years before returning here in March. He moved here with his wife, Australia’s most decorated cycling Olympian Anna Meares, and their two children.

Meares, who was world champion in every track speed event, has been a mentor for Ellesse.

“Ellesse was 15 when she first met Anna while she was helping at a World Cup in Cambridge, and Anna signed her drink bottle,” Mote-Andrews says.

Ellesse Andrews with her fellow team sprint gold medallists, Rebecca Petch and Olivia King.

At the start of the individual sprint competition on the weekend – after Andrews had already won gold in the team sprint, and stepped in to help the one-woman-down team pursuit trio win silver – Flyger noticed Andrews wasn’t her usual self.

“Nick said to Ellesse: ‘It doesn’t seem like you’re quite switched on at the moment, what can we do to turn that around?’” Jon Andrews says. “Ellesse went for a walk outside the stadium, out of the environment, put her music on, had a bit of a reset, and walked in and then, boom. From then on everything snapped into place.

“That’s a huge turnaround for her, too. Look back at Tokyo, when she won her keirin medal, how emotional she was. What you see with Ellesse is exactly what you get; she’s totally honest in her emotions.

“At the Olympics, she was so emotional, so happy, but that takes a lot of energy out of you; the next day when she raced the sprint, she was emotionally and physically exhausted.” She still managed to finish fifth.

“This time she was able to keep a lid on it, so she could bring it again the next day,” says Mote-Andrews. “So, she didn’t mentally fatigue herself. And that’s about maturity, too."

Her mum also believes Ellesse’s love of performance is helping on the track. “It’s part of our family ethos,” says Mote-Andrews, a musician and composer. “She’s very good on the stage, too; she was a dancer and she's a very powerful singer.”

In fact, Ellesse did some singing gigs around Cambridge, where she lives, before heading overseas to ride.

A little over a fortnight ago, while she was in isolation for a week in Grenchen, Switzerland, suffering from Covid, she tried to buy a guitar online. “She doesn’t like not having something to do,” her dad says.

***

Within an hour of each other yesterday, Andrews and her endurance cyclist team-mate Aaron Gate became two of only five New Zealand athletes to have won three gold medals at a single Commonwealth Games.

They joined Dame Yvette Williams, who won three athletics medals at the 1954 Games in Vancouver (the discus and the long jump at the same time); weightlifter Darren Liddel at the 1998 Games in Kuala Lumpur; and Jon Andrews’ track team-mate at the 1990 Games in Auckland, Gary Anderson.

Still living in his hometown of Whanganui, Anderson has watched Andrews and Gate in admiration this past week. He won his own trio of golds in the individual and team pursuits and the scratch race, and also narrowly beat Jon Andrews for silver in the kilo time trial at the same Games.

When asked how an athlete can lift themselves mentally and physically to win multiple golds over a few days, Anderson says in his case, he trained harder than he competed.

“At a track cycling meeting you’re always extremely busy, putting out an absolute max effort two or three times a day. But in training, I might have put out a similar effort 10 times a day,” says Anderson, who won Olympic bronze two years later.

“It’s taxing mentally, warming up, warming down, but you’ve trained so hard leading up to it, it just becomes part of your day. Before riding four events at the 1986 Commonwealth Games, I was told it would be too much, but I was prepared for it. And I did it again in 1990.

“You approach it one event at a time. And when you’re in fantastic form, you feel like you can do anything.”

An unforgettable first day for the NZ track cycling team at the 2022 Commonwealth Games

That may also be part of the reason Andrews came to the rescue of the Kiwi team pursuit women, who wouldn’t have been able to start without a fourth rider after Ally Wollaston fractured her wrist in the Tour de France Femmes last week.

“Stepping in to help the team pursuit was a great example of her character. She knew how much work they’d put in and she wanted to help them,” Jon Andrews says.

She wasn’t too worried about not receiving her silver medal, her parents says, when she skipped the ceremony to prepare for her team sprint final (she was also fined and docked UCI points). Helping her friends was enough reward.

***

Andrews began studying towards a bachelor of social sciences, majoring in psychology, at the University of Waikato back in 2018. It’s very much a work in progress.

“She’s still a first-year student; she’s picking away at it,” Mote-Andrews says. “She gets so tired with her training, she really struggles to study as well.”

Following her success at the Tokyo Olympics, her parents put it to her she had “all the ingredients to become really dominant” in world sprinting. Especially her aerobic capacity from her endurance days to sprint longer.

The Andrews stress there’s never been pressure on Ellesse, or her younger sister Zoe, to follow in their footsteps. And from a young age, Ellesse has always managed to shrug off the pressure of being as good as her dad.

“The focus has always been on fun,” he says. “We knew if we pushed her she’d be most likely gone from the sport, and that would be a massive loss.

“We encouraged her to keep playing netball, to do swimming, dance, music and singing. She eventually made up her own mind that she quite liked winning bike races."

Mitchell, a sprinter who went to the Tokyo Olympics with Ellesse before he retired earlier this year, reckons her new-found self-belief helped drive her to three golds this week.

“As a young athlete from New Zealand, who was an endurance rider just three years ago, and not necessarily having all the race experience other nations get from a geographical perspective… to have the belief she has the class and the form to do it is probably one of the most admirable qualities in Ellesse,” he says.

“To back herself and put herself in a position to win multiple events is amazing. The difference between the individual sprint and keirin, in terms of what you need to do physically, is quite different - and she just won both. Not many people have done that.

“In New Zealand, we’re pretty quick to play the humble card which can get in the way of our performance. But I’d put her success down to a natural belief in her ability, and trust in her processes.”

Mitchell also gives some credit to the work Andrews did as a young endurance rider to help her recover between events. “And maybe that shines a light on the fact sprint athletes could do a little more aerobic work,” he says.

“She’s one of those individuals who’s incredibly determined to the point of being stubborn. I remember training with her and where most people would have shied away from an effort with the guys, she jumped at the chance. She always wanted to see where she could get one over us.”

***

New Zealand’s track cycling team has performed beyond expectations at these Games – 13 medals, including a record eight gold. It’s astonishing when you think of the public turmoil the sport has been in over the past 12 months.

August 9 will be the first anniversary of the death of Olivia Podmore. A New Zealand sprinter at the 2016 Olympics and 2018 Commonwealth Games, she was a training partner and team-mate of Andrews.

Podmore's suspected suicide sparked an independent inquiry into Cycling NZ’s high performance system, and the resulting report was highly critical; a 10-point action plan - including investing more in female health and giving athletes a greater voice - was released a fortnight ago. A number of people at the apex of the sport have left in the past year.

“The most important thing is everyone misses Liv. We love her as a team-mate and a friend, and she’s always held in my thoughts,” Andrews told Stuff on the eve of these Games.

Jon Andrews says the past year has been tough on Ellesse and the rest of New Zealand’s elite riders: “It’s been a horrendous time, with lots of emotions - extreme sadness, but also anger, which is totally normal.

“It’s been a year of total destruction, and Olivia has never been far from their minds. But the athletes have managed to continue to be strong, getting on with what they do best.

“It’s a testament to the riders to see them perform the way they did. No one ever imagined they would have gone quite so well.”

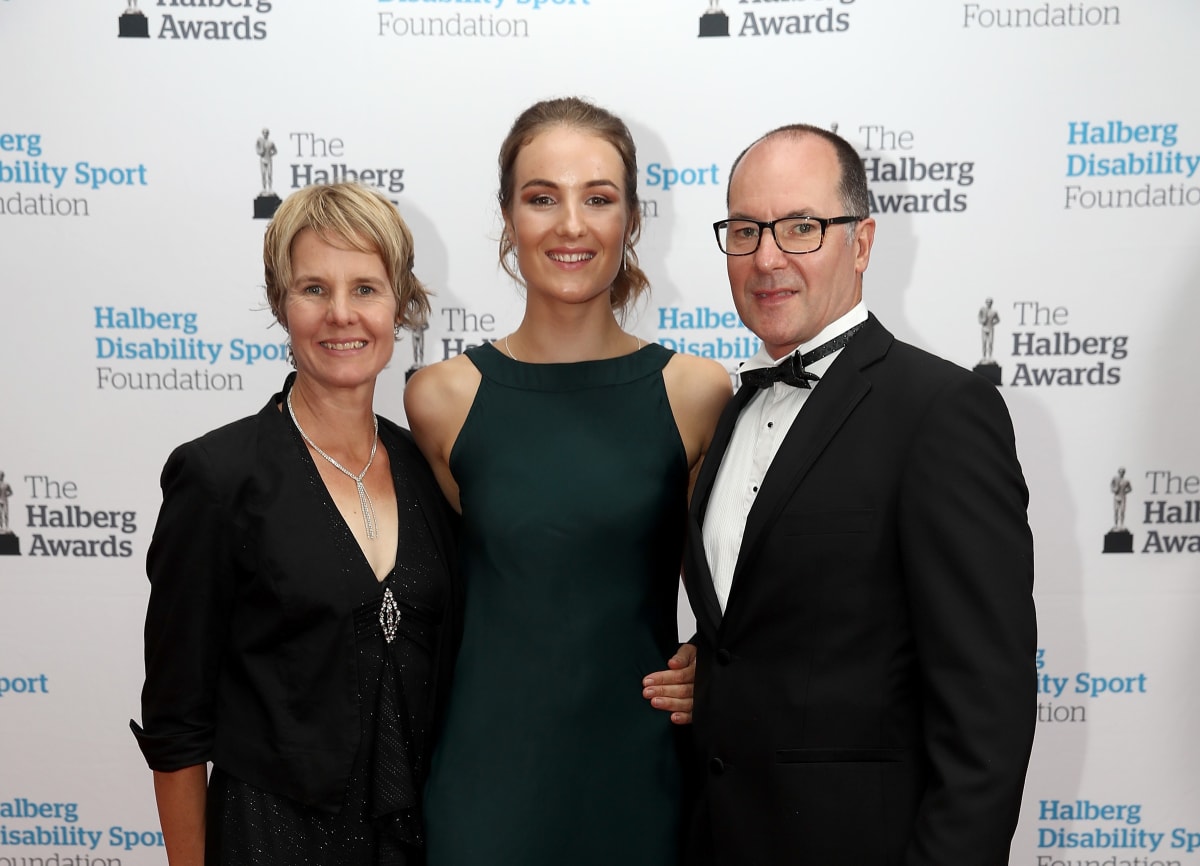

Andrews’ parents had decided not to travel to Birmingham. “It’s because Jon is working with the Australians,” Mote-Andrews laughs before heading off to work as a music teacher (on little to no sleep).

He’s coaching the Australian under 19 sprint team at the junior world champs in a fortnight in Tel Aviv. “When we went to book our flights to England, they were too expensive,” he says.

But the couple will follow their daughter to the senior world track championships in Paris in October.

Angela’s parents, John and Jenny Mote, were there representing the family; Andrews rode over to the stands and hugged them after winning her latest race.

You get the feeling that there will be many more opportunities to watch Andrews fly around a track.

“She’s so incredibly talented, whatever she puts her mind to she will achieve it,” Ethan Mitchell says. “Now I hope she believes she’s a real player on the world sprint scene.”

But she could also succeed on the road or in mountain biking, he admits. “She’s the kind of athlete who could decide next week she wants to do the Coast to Coast, and then do it.”