This feature originally appeared in Cycling Weekly magazine on 25th July. Subscribe now and never miss an issue.

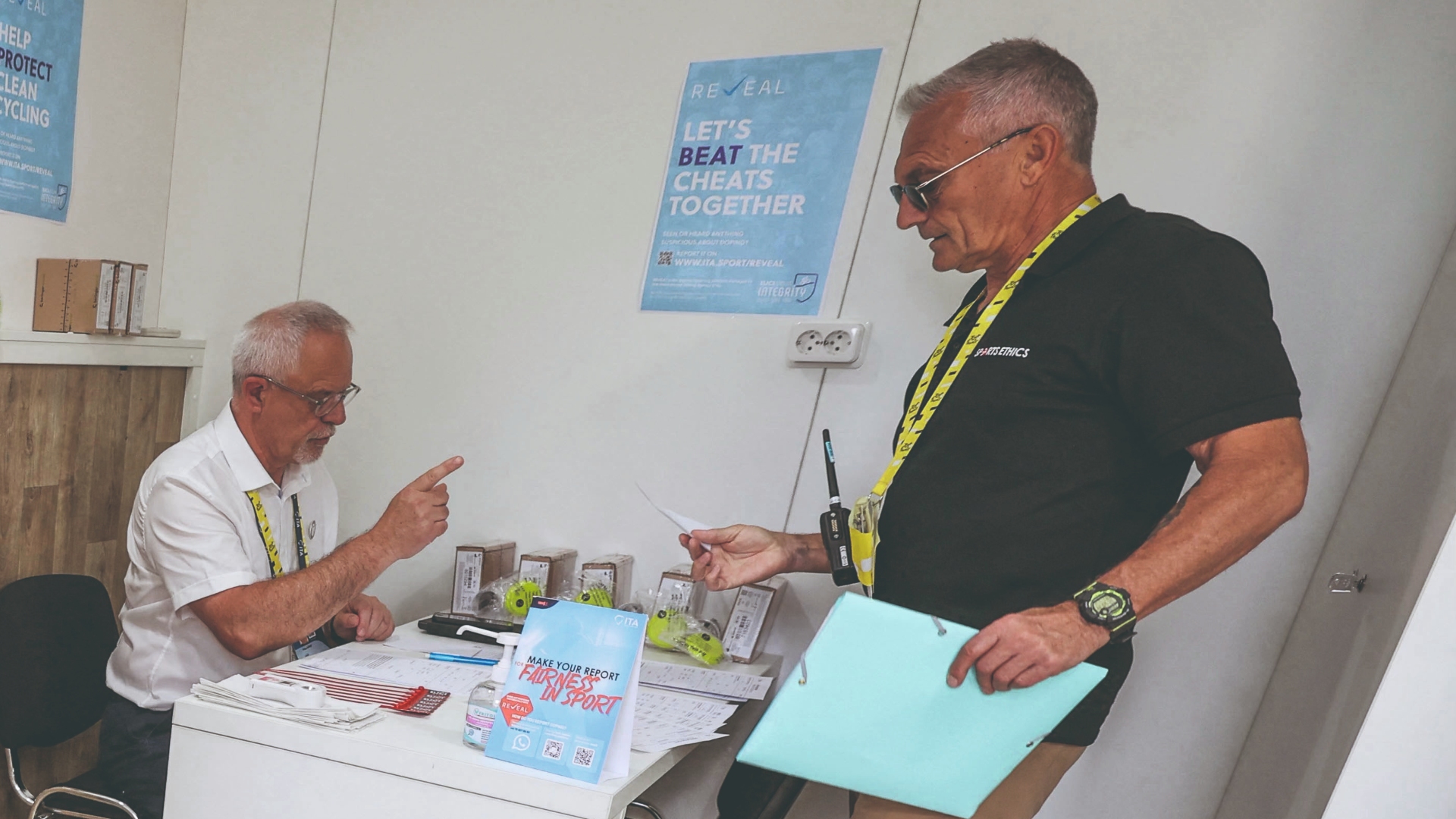

Of the many thousands of vehicles at the Tour de France, the anti-doping truck is the most secretive, blocked off by high black fencing with a security guard permanently stationed outside. On the race’s first time trial, however, I’m waved through various checkpoints and allowed into the operations centre that is tasked with maintaining the integrity of cycling’s biggest event. Led up the steps of the long white truck, I’m shown into the first of two unremarkable, plain portable offices, featuring a desk, lots of anti-doping posters, and a bathroom with mirrors on all four sides.

On average, eight riders per stage are required to give a urine sample at the Tour (at the cost of just under €1,000 per test), including the stage winner and the yellow jersey, and they must follow a strict protocol: after a chaperone notifies them of their obligation to provide a sample and they’ve signed a disclaimer form, they then roll their bibshorts down to their knees and their jersey up to their chest, and urinate into a small plastic pot called the testing vessel, with a doping control officer (DCO) watching at all times to ensure that no third-party liquid is used instead. The urine is then poured into A and B vessels, and stored in a coolbox between 2°C and 8°C before being sent for analysis.

The 2024 Tour has passed off without any doping violations, and the sport appears to be light years away from the EPO and blood doping days of the 1990s and 2000s. But violations do still occur; EF Education-EasyPost terminated the contract of Andrea Piccolo just before the Tour after he was accused of importing human growth hormone into Italy. It was a timely reminder that the fight to ensure a clean Tour de France is a never-ending one.

The process

Of course anti-doping tests and protocols don’t start and finish at the races. Athletes can be tested by their national anti-doping organisation, such as UK Anti-Doping in Britain, and also by their international federation. Since 2021, the UCI has delegated all its testing to the International Testing Agency (ITA), a body that is independent from international governing bodies. The ITA is responsible for all anti-doping tests at the Tour de France and other WorldTour races.

In deciding which athletes ought to be tested on any given day, DCOs assess the following risks: the athlete’s performance; the level of testing in their country; intelligence and information; and any discrepancies in their athlete biological passport (ABP) – a record of blood test results over a period of time. “All tests are targeted – there are no random tests,” Olivier Banuls, the ITA’s head of testing and cycling unit tells me in late May from the organisation’s Swiss offices on the shores of Lake Geneva.

Once an athlete has been identified, they must provide a sample – refusing to do so would class as a missed test; three incomplete tests would result in a ban. The sample is then sent to a World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)-accredited lab for analysis; there are 30 such labs worldwide, but only one in France, in Paris. All samples have to be tested within 20 days and the result is uploaded to WADA’s anti-doping administration and management system (ADAMS), a programme that stores an athlete’s testing history and results. At the Tour, however, the ITA rushes through the analysis within 72 hours; it’s even faster at the Olympics, with a 48-hour turnaround.

All samples are mandatorily tested for the same undisclosed performance-enhancing drugs, but additional substances can and are also tested. “We want to make sure that we are testing the athletes for the potential substances that they might take,” says Banuls. According to a WADA report reviewing testing in 2022, EPO was only tested for in the samples of 45% of cyclists, while human growth hormone and synthetically derived steroids such as testosterone were only tested 8.5% and 2.5% of the time, respectively. The ITA says that “testing for EPO is not mandatory and rather expensive, so it would be neither smart nor cost-effective to perform this analysis on all samples.”

Along with the urine samples collected in the anti-doping truck, around 400 blood samples are taken during the Tour, mostly in hotels and occasionally on team buses. All these must be analysed within 48 hours.

Evading testing

It’s not just in the race that a Tour de France cyclist will be tested, of course: out-of-competition tests are just as crucial. The ITA tells me that, on average, each of the circa 1,000 professional cyclists are tested four times a year away from racing; higher-profile riders are tested more often, particularly in the run-up to major events. Teams also have an obligation, as per UCI regulations, to inform authorities several months out where their riders are scheduled to be training and competing.

Athletes have to provide information about where they’ll be sleeping, travelling and training for every 24-hour period, and also state a daily one-hour daytime slot when a DCO can test them. Even then, a sample can be taken outside of this window, Banuls stresses. What happens if a rider doesn’t answer the door when it’s outside of the hour they propose? “It’s not a missed test but classed as a filing failure and an unsuccessful attempt,” Banuls says. “The DCO will report to the testing authority who will decide whether or not to prosecute this potential whereabouts failure.” So it’s hard to avoid testing? “It’s very difficult,” he says. “The ratio of unsuccessful attempts outside of competition in cycling is extremely low – we’re talking about 5%.”

A practice that is worrisome to authorities is micro-dosing: doping with very small and hard-to-detect amounts of banned substances. “We’re aware of this potential risk,” Banuls says. “We may not be able to identify that the athlete is micro-dosing with direct direction, but we could do via the variations of biological passport markers.” Authorities also keep a selection of samples rated as high importance for 10 years, allowing later re-analysis. “Today, we might not be able to detect [a micro-dosed] substance, but we might be able to in eight years,” Banuls explains.

CHALLENGES TO THE ABP: the athlete biological passport, introduced in 2008, is still considered an important tool. Indeed, in June Australian rider Rob Stannard was given a four-year ban, backdated to 2018, for abnormalities in his ABP. However, the ABP does not enjoy universal support: Spanish rider Ibai Salas was banned for six years in 2018 for ABP irregularities, but he had the ban overturned last year and has claimed a six-figure compensation sum when Spain’s highest court ruled that the ABP was not a valid method in determining a doping offence. The case puts a question mark on the ABP’s resilience.

CONTAMINATION CONCERNS: in March, British rider Lizzy Banks had her suspension lifted by Ukad after arguing that her positive for chlorthalidone and formoterol was caused by contamination. Visma-Lease a Bike’s Michel Hessmann was given a four-month suspension in June for low levels of chlorthalidone, but like in Banks’s case, the German anti-doping agency found that the result probably resulted from contaminated medicine.

ROXADUSTAT: used legitimately for those with anaemia, it can boost the production of the body’s red blood cells. It’s been likened as similar in effect to EPO. Tennis player Simona Halep received a four-year suspension for roxadustat in 2022, but had it cut to nine months after proving a contaminated supplement. used legitimately for those with anaemia, it can boost the production of the body’s red blood cells. It’s been likened as similar in effect to EPO. Tennis player Simona Halep received a four-year suspension for roxadustat in 2022, but had it cut to nine months after proving a contaminated supplement.

TAPENTADOL: an opiate-based painkiller described as “10 times” stronger than the now- banned tramadol, the UCI has asked WADA to add the substance to its monitoring programme with a view to eventually banning it.

GENE/CELL DOPING: the manipulation of genes, using gene or cell transfer, to alter their expression and function to enhance athlete performance. “It’s considered by WADA as a potential risk and threat so therefore we take it very seriously,” Banuls says. There has never been a confi rmed case.

A clean tour?

It might surprise you to know that the UCI is unable to intervene at any point in this process. “The ITA is absolutely independent and fully autonomous, with no space for interference,” Banuls states. “We collect samples on the UCI’s behalf, send them to labs, and the results are reported into ADAMS by obligation. Once it’s in ADAMS there is no way of hiding anything.”

So are the performances we have enjoyed watching at the Tour de France trustworthy? Will the results stand the test of time? Banuls refuses to answer directly, pointing only to an increase of 35% in the ITA’s budget in the past two years. “What people can trust are the eff orts taken by the ITA, UCI and all stakeholders to protect the sport,” he says. “We tested 15,200 samples in 2023, which is a huge number, and 10% more than 2022, and our intelligence and investigations team has doubled.”