Scientists have invented an injectable "goo" that can regrow cartilage in the body. For now, they've only tested it in sheep, but it could someday be used to repair joint damage in humans, the researchers say.

In particular, they hope the goo can treat damage caused by degenerative diseases, such as osteoarthritis, and sports-related injuries, including anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears.

Cartilage is a strong, flexible tissue that lines the surface of joints, such as the knees. It cushions the joints and prevents the bones within them from grinding against one another during movement. But as we age, the cartilage in our joints gradually deteriorates. It can also become damaged by injury or as a result of chronic overuse. As the cartilage wears away, people may experience joint pain and struggle to walk.

"When cartilage becomes damaged or breaks down over time, it can have a great impact on people's overall health and mobility," co-study author Samuel Stupp, director of Northwestern University's Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology, said in a statement. "The problem is that, in adult humans, cartilage does not have an inherent ability to heal."

Related: Blood test powered by AI could catch osteoarthritis 8 years earlier than X-ray, early data show

That's largely because cartilage doesn't have an active blood supply. As a result, surgery is often needed to repair damaged tissue.

One of the main treatments for cartilage damage is microfracture surgery. During this procedure, surgeons remove damaged cartilage and then create holes in the underlying bone. This enables blood containing specialized growth chemicals to flow into the area, which then triggers cartilage growth. However, often the cartilage that forms after this surgery — fibrocartilage — is weaker and less resistant to wear and tear than the cartilage normally found in joints, called hyaline cartilage.

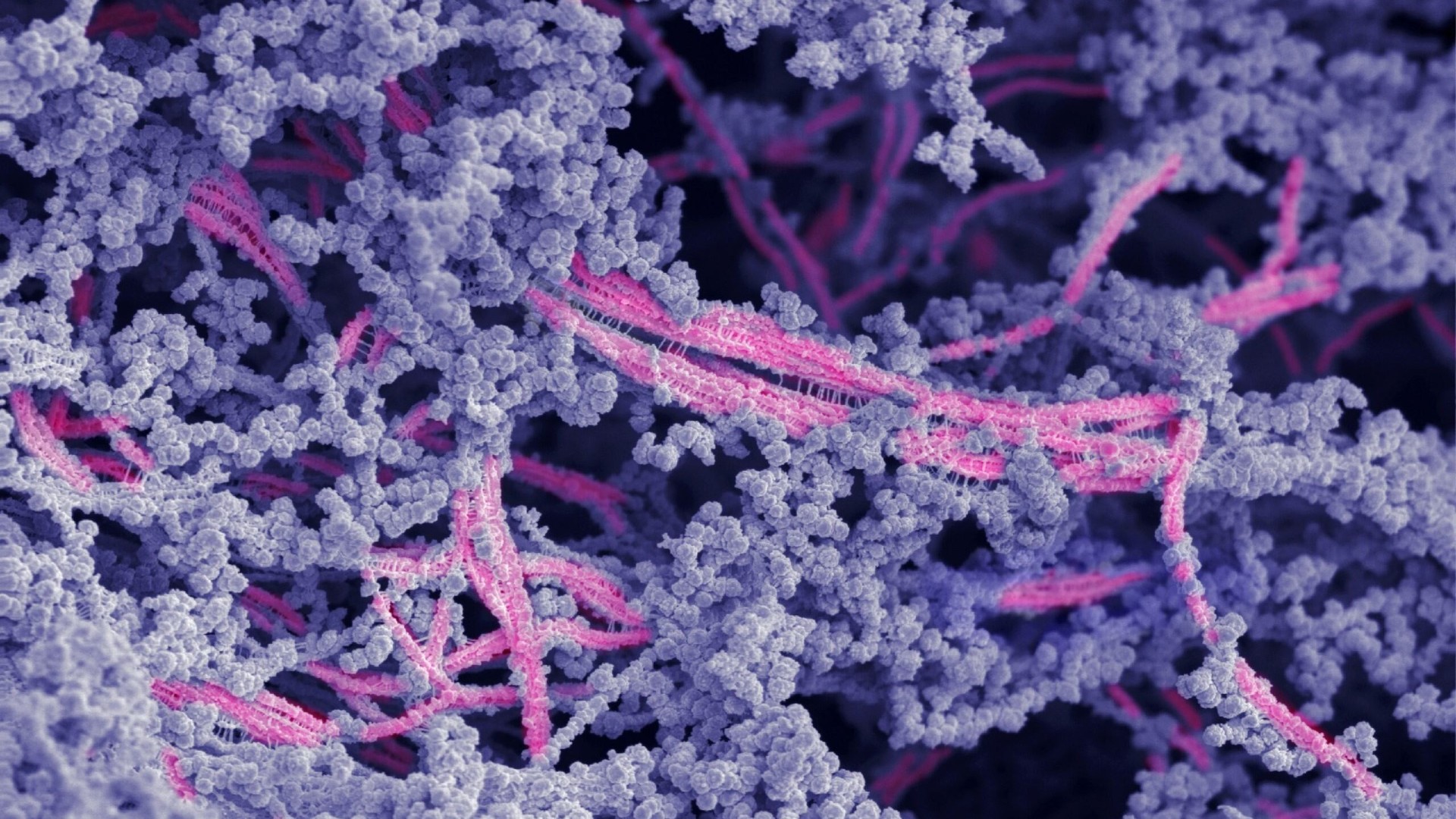

Now, Stupp and his colleagues have created a type of injectable biomaterial that can regenerate the hyaline cartilage in joints. They described their invention in a study published Monday (Aug. 5) in the journal PNAS.

"Our new therapy can induce repair in a tissue that does not naturally regenerate," Stupp said.

Once injected into a joint, a protein within the goo recruits a chemical in the body called transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-b1), which promotes cartilage repair. The goo also contains a type of complex carbohydrate, or polysaccharide, called hyaluronic acid, which can coax stem cells into forming cartilage.

The researchers tested the goo in sheep that had a type of cartilage defect in their stifle joint — a complex joint that resembles the human knee and is found in the upper back legs of four-legged animals.

Within six months of the one-time injection being delivered, the goo triggered noticeable cartilage growth and enhanced repair in the animals' damaged joints. The new biomaterial performed better than injections of just TGF-b1, which were given to a comparison group of sheep. Importantly, the structure of the new cartilage in the sheep treated with the goo resembled that of hyaline cartilage, the team found.

With further research and development, the team hopes that the goo will produce similar results in humans.

"By regenerating hyaline cartilage, our approach should be more resistant to wear and tear [than microfracture surgery]," Stupp said.

This could fix the "problem of poor mobility and joint pain for the long term while also avoiding the need for joint reconstruction with large pieces of hardware," such as prosthetic joints, he said. The hope is that, eventually, something like the new biomaterial could be used to prevent the need for full knee-replacement surgeries.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!