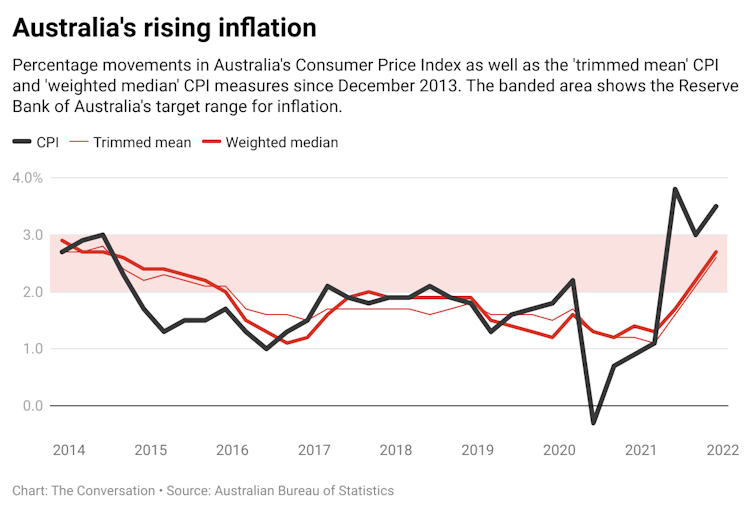

Australia’s Consumer Price Index rose 1.3% in the three months to December, bringing inflation for the full 2021 year to 3.5%.

This is above the Reserve Bank of Australia’s medium-term target range of 2-3% inflation. It will excite speculation about the central bank lifting interest rates far sooner than 2024, as the bank’s governor Philip Lowe suggested was most likely in 2020.

But don’t expect Lowe and the Reserve Bank’s board to be spooked into a rate rise so easily.

Central banks like a little inflation but not too much. History shows prices either falling or increasing too rapidly are bad for an economy. When inflation rises above the sweet spot, the normal response of a central bank would be to cool demand by lifting interest rates (through the interbank interest rate known as the cash rate, which then flows into many other interest rates such as on home loans).

These, however, are not normal times.

The CPI (which measures inflation using a weighted “basket” of consumer goods and services bought by the typical household) has been distorted by the COVID-19 pandemic and government responses.

Read more: What's in the CPI and what does it actually measure?

As the Australian Bureau of Statistics notes, the two biggest contributors to the CPI lift have been automotive fuel and new dwelling purchases.

Fuel prices fell markedly due to people driving less, and have now rebounded to an all-time high. The federal government’s HomeBuilder grant scheme introduced as part of its COVID-19 response distorted the cost of buying new homes.

The Reserve Bank therefore concentrates on a measure of “underlying inflation”, which is less affected by atypical movements in a few prices. The ABS measures this using a “trimmed mean” – excluding those items with the largest and smallest price increases before taking an average of the remainder.

Compared with the headline CPI rate of 3.5%, the trimmed mean is 2.6% – well within the Reserve Bank’s target range.

Read more: Now that Australia's inflation rate is 3.8%, is it time to worry?

So how will the Reserve Bank respond?

At its most recent meeting (on December 7), the Reserve Bank’s board reiterated it “will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range”.

Lowe said the same in a speech on December 16. “We are still a fair way from that point,” he said, adding a rate rise probably wouldn’t happen in 2022:

It is likely to take time for that condition to be met and the Board is prepared to be patient.

These latest quarterly figures are unlikely to convince the Reserve Bank board the time for patience is over.

Read more: Vital Signs: RBA governor Philip Lowe's dangerous game on interest rates

Omicron influences

Financial markets have been pricing in an interest rate rise in the first half of 2022 for months.

Given this is contrary to the signals from the Reserve Bank, it is worth assessing how the latest CPI figures fit with the central bank’s story about what is driving inflation.

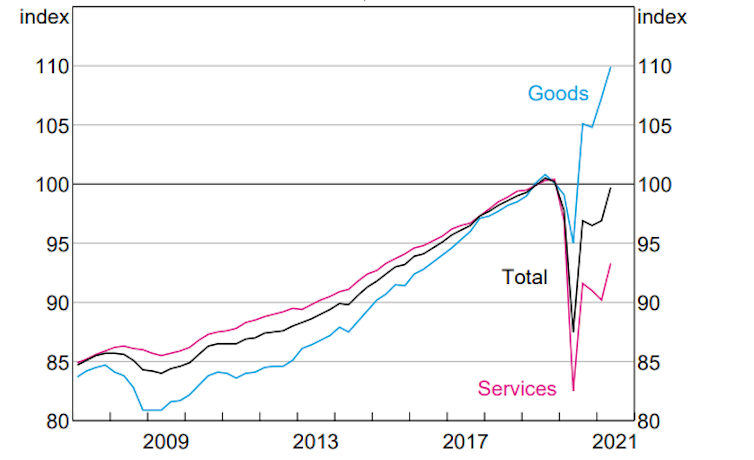

In November 2021, Lowe pointed out that the pandemic had prevented households spending on services such as holidays, cinemas and restaurants. Consumers had therefore switched to spending more on goods. This exacerbated the pressures on supply chains (already affected by workers being sick or confined to home) and bid up some prices on goods. But these effects, he said, were likely to be temporary.

The CPI numbers are consistent with that story. While the price of services grew by 2.3%, goods rose by 4.3%.

Changes in household consumption of good and services in G7 nations

Inflation should decline once supply chains are operating more normally.

Granted, the Omicron outbreak has complicated the outlook – exacerbating supply problems while lowering consumer confidence and hence demand. The impact on inflation is unclear. But this too should be temporary.

Read more: Inflation will probably melt away in 2022 – central banks will do far more harm trying to tackle it

Few signs of wages growth

The unemployment rate ended 2021 at 4.2% (albeit measured before the impact of Omicron). It may go up again in January due to Omicron’s effect, but should then get even lower during the course of 2022.

Yet so far there’s no sign of low unemployment translating into large wage increases, with average wages in the 12 months to September 2021 (the latest data) growing by just 2.2%.

This subdued wage growth contrasts with the US, where annual growth is almost 5%. Part of this is to do with a drop in labour force participation, dubbed the “great resignation”.

In the UK, wage growth is about 4%, with contributing factors including worker shortages due to Brexit.

Measures of wages growth in New Zealand are between 2% and 4%.

Read more: It's great to want wage growth, but the way we're going about it could stunt the recovery

The inflationary pressures from rising wages has led some central banks to raise their cash rates. But things are different here.

Lowe has said “it is likely wages will need to be growing at 3 point something per cent to sustain inflation around the middle of the target band”.

So the prospect of the Reserve Bank of Australia lifting interest rates any time soon continues to look doubtful.

John Hawkins formerly worked for the Reserve Bank.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.jpg?w=600)