Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has adversely impacted Indonesia’s economy. This crisis, which has also hit many other countries, is a consequence of the massive cessation of economic activities due to restrictions to suppress COVID-19 case numbers.

Southeast Asia’s largest economy, Indonesia is now trying to help its economy rebound to pre-pandemic levels or even higher through its National Economic Recovery (PEN) program.

Unfortunately, this recovery program relies heavily on fossil fuels to meet the country’s energy needs. This needs to change, as economic recovery should be in line with Indonesia’s climate commitment to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060.

Indonesia is already among the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters. Without aggressive efforts to reduce the use of fossil fuels and increase cleaner and renewable energy capacity, Indonesia’s COVID recovery program could actually create more problems.

Recovery without sustainability

Indonesia’s support for the use of fossil fuels is reflected by the allocated funds, reaching about 8% of the total National Economic Recovery budget.

The economic recovery program has 15 strategic measures to support the energy sector. Most of those measures are likely to benefit the fossil fuels industry, instead of the new and renewable energy industry.

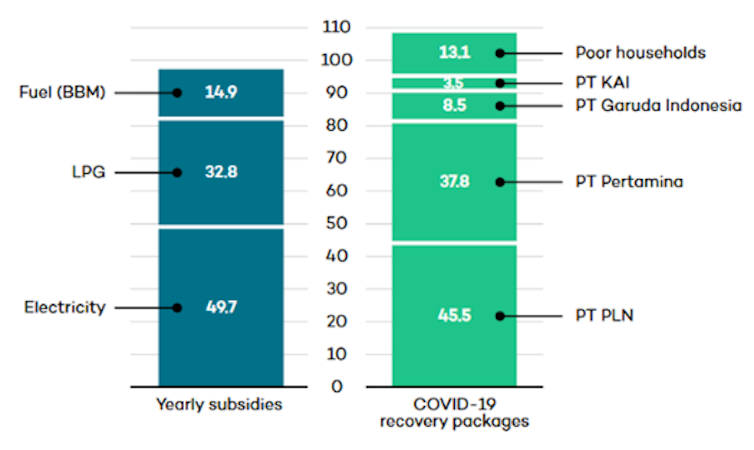

The most significant funding allocated to the energy sector, Rp 95.3 trillion or around US$6.4 billion, has been given to State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) linked to fossil fuel energy, including oil and gas firm Pertamina, power firm PLN, airline company Garuda Indonesia, and train operator KAI, to support their businesses.

In addition, Rp 13.1 trillion or US$886 million is disbursed to subsidise electricity for poor households, predominantly generated from burning coal.

In 2020, the Indonesian Government also continued the yearly subsidies of Rp 97.3 trillion or US$6.5 billion for different types of fossil energy, such as electricity, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and gasoline.

In contrast, the National Economic Recovery program only specified a subsidy for one type of renewable energy, biodiesel.

Meanwhile, support for other types of new and renewable energy is mentioned, but without details on the allocation of funds or programs. For example, the recovery program says it supports incentives for the installation of rooftop solar power panels for private customers. However, the implementation of this support is unclear.

Policies supporting fossil fuels are an instant way to ramp up the economy. However, this could come back to hit Indonesia’s economy and Earth’s sustainability in the medium to long-term.

A recent example is a surge in world oil prices that reached US$100 per barrel as an effect of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This rise has caused the Indonesian government to dither about allocating funds for gasoline and LPG subsidies. Consequently, the surge in oil prices has increased the prices of other goods and services.

Increased industrial activities are also associated with poor air quality, especially in urban areas. Recently, Switzerland-based air quality watchdog IQAir recorded Jakarta as the most air-polluted city in the world.

Indonesia’s strong dependence on fossil fuels has long hindered the growth of clean energy. Before the COVID-19 crisis, more than 90% of Indonesia’s total energy demand was supplied by fossil fuels, with coal use rising much faster than any other energy source.

If this trend continues, Indonesia is less likely to achieve its net-zero emissions target in 2060.

Balancing energy security and energy transition

The Indonesian government needs to review its energy strategy transition so that its net-zero emissions target and national economic recovery can both be attained.

The government also needs to harness environmentally-friendly technologies and a multitude of new and renewable energy resources.

The government needs to take advantage of environmentally-friendly technologies and renewable energy with the potential to promote sustainable development.

In the industrial sector, carbon capture and storage technology could be applied to store carbon dioxide underground at a relatively low cost. This cost of this technology for the industrial sector with highly concentrated carbon dioxide streams is cheap.

Through this technology, industries with high energy demands could potentially continue to run on fossil fuels in the short to medium term with a lower carbon footprint. As a result, carbon capture and storage may help in minimising the pressure on renewable energy growth for heavy sectors during the early phase of energy transition.

The government also needs to provide support for reliable and inexpensive clean energy sources. Geothermal, hydro and nuclear energy are all types of clean. In addition, the excellent geothermal and hydro energy resources in Indonesia are considerable and low-cost. Although nuclear power plants have very high upfront capital expenditure, they are relatively cheap to run.

In addition, abundant sunshine and decreasing costs of solar panels are the main drivers for harnessing solar energy in Indonesia, mainly to supply electricity for homes and office buildings.

Last but not least, Indonesia should develop energy storage technology such as batteries, pumped storage hydro power and hydrogen to ensure reliable renewable energy supply.

The government could implement the above recommendations gradually while taking strategic measures related to financing and supporting policies. In this instance, the government should increase subsidies for the renewable sector to stimulate the market growth for cleaner energy in society and industry.

The government can source the funding needed by cutting current high subsidies for fossil fuels and implementing a carbon tax, particularly for high-emitting industries.

In addition, Indonesia, which currently holds the G20 presidency, has a strategic position to attract domestic and foreign stakeholders to invest in Indonesia’s low-carbon technology and renewable sector.

Zalfa Imani Trijatna has translated this article from Indonesian languange

Denny Gunawan is affiliated with the Energy Commission, Directorate of Research and Studies, and Overseas Indonesian Students' Association Alliance (PPI).

Elisa Wahyuni is affiliated with the Energy Commission, Directorate of Research and Studies, and Overseas Indonesian Students' Association Alliance (PPI).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.