The Indonesian government has claimed that its raw nickel export ban, which started in January 2021, has shown positive impacts after seeing increases in mining investments and exports of nickel-derived products.

This statement seems to be premature, considering that the government has failed to disclose the data that can support this argument.

The Indonesian government has long desired to add high value to domestic mining products, especially nickel, through downstreaming.

Nickel is a major component in electric batteries, which have become increasingly important due to the rising production of various gadgets and electric cars that require energy storage.

As the country with the world’s largest nickel ore production and reserves, Indonesia has a vital role in the global nickel trade. Indonesia produces 1 million metric tons per annum or 37% of the worldwide nickel production of around 2.7 million metric tons.

Indonesia has placed a ban on raw nickel exports in hopes of adding value to domestic nickel products.

Economists generally discourage market interventions like export bans as they hurt economic efficiency. A nickel export ban might disturb global nickel supplies and trigger trade conflicts. This is evident in the European Union’s filing of a dispute at the World Trade Organization (WTO) on Indonesia’s export ban policy.

With the above in mind, it begs the question as to whether Indonesia’s export ban actually creates a positive impact on the downstreaming of nickel products.

Export ban: increased investments and export of derivative products

The implementation of the export ban has not always been smooth. In 2014, the government tried banning mineral exports. The government revoked this restriction in 2017 due to dropping nickel productions, sluggish smelter developments and trade balance deficits.

In 2020, as some smelters became operational, the government again banned mineral exports, particularly for low-grade nickels.

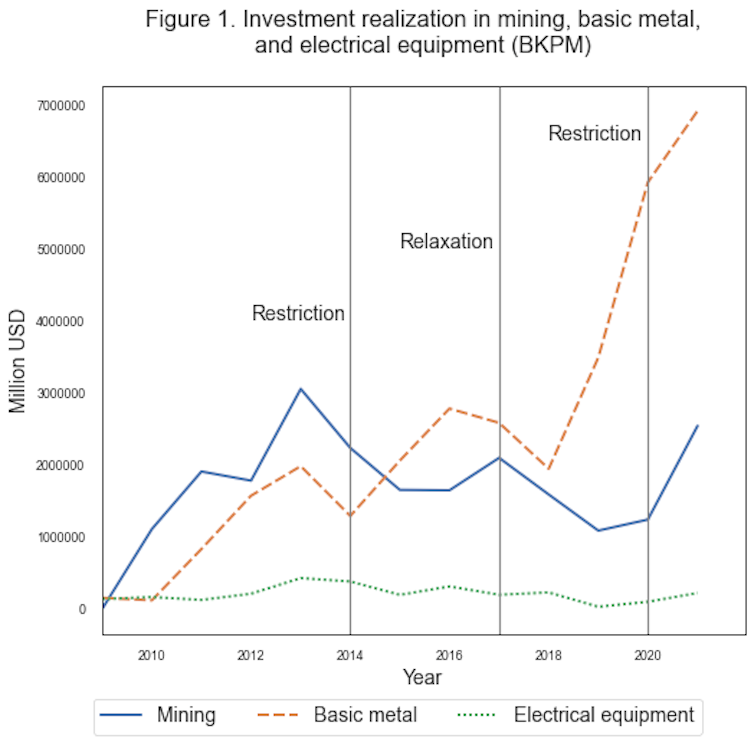

The government argued that banning nickel ore exports has successfully increased basic metal industry investments, especially in nickel smelter developments. This statement has been backed up by data from the Indonesian Ministry of Investment presented below.

The data show that investments in the mining industry dropped in 2014 when the government introduced a ban on nickel ore exports, taking away one of the main incentives for investment. However, in 2021, data show that investments in the industry increased from the previous year, indicating that an export ban does not hurt investment as supplies are absorbed by the domestic market.

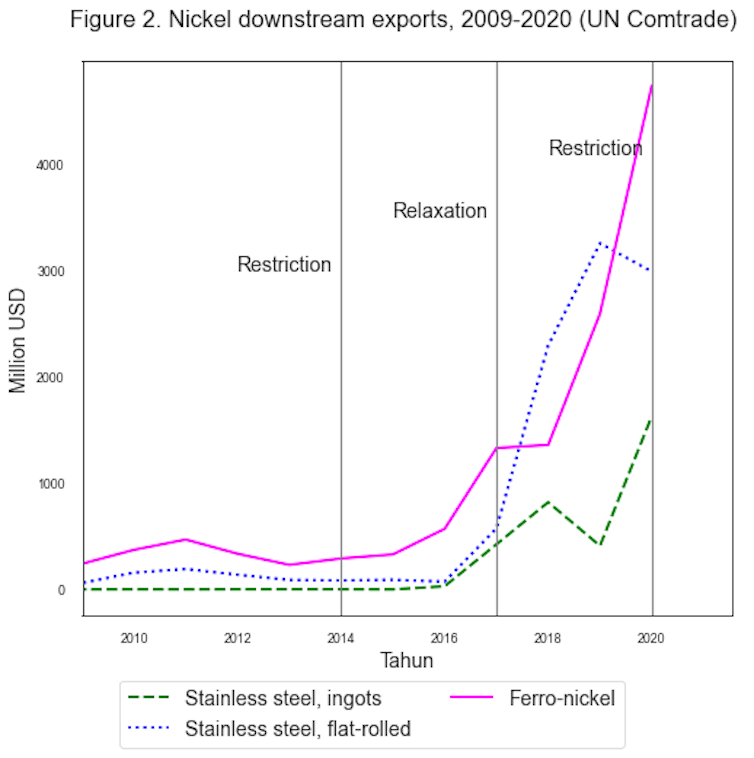

The government also claimed that 2021 saw the exports of value-added nickel products, such as stainless steel.

As investments in the basic metal industry increased, the production of value-added nickel products also rose. Figure 2 shows nickel-based productions ups and down were influenced by the ban in 2014, relaxation in 2017 and reimplementation of the ban in 2020.

The two indicators — increased investments and exports by the downstream mining industry — have encouraged the government to expand the mineral export ban on other products, including tin and copper.

However, a question remains as to whether investment and export figures make a precise indicator to evaluate the success of the export ban strategy.

Measuring the dynamics of added value

It is correct to say that the value of exports of value-added nickel products is higher than the lost value of nickel ore exports.

However, if the government intends to add value at the domestic level, measuring success using exports is not accurate.

Measuring the shift in the value chain, especially with interventionist policies like an export ban, need detailed assessments.

The first issue is the potential loss of government revenue.

Banning nickel exports means revenue losses from corporate taxes and export duties. This also means that state revenues from the downstream nickel industry must cover the losses. On the other hand, however, enticing smelter investors to Indonesia requires not only a nickel export ban but also tax incentives.

The government offers smelter companies a tax holiday—from corporate income tax deductions to exemptions, and their products are exempt from export duties.

The second issue is about transferring added value from mining companies to the smelters. The export ban has forced mining companies to sell their nickel ores to domestic smelting companies. Mining companies must accept a far lower price amid the currently high global nickel price.

The nickel export ban, in sum, has caused value losses in the mining sector. This loss has been exacerbated by problems surrounding domestic nickel selling pricing and grading systems.

The third issue is employment. The government argued that adding value to mining products would open new industries and new job opportunities in Indonesia.

Nevertheless, despite the possible increase in employment rate, especially in the smelting sector, the government must also measure the possible downsizing in the mining sector due to the nickel export ban.

Unfortunately, Indonesia does not have reliable employment data in the mining sector. Available data show that the proportion of basic metal industry workers in the Indonesian workforce has not demonstrated any perceptible increase.

The three issues mentioned above illustrate that measuring added value based on export bans and tax incentives is more complex than the government has argued.

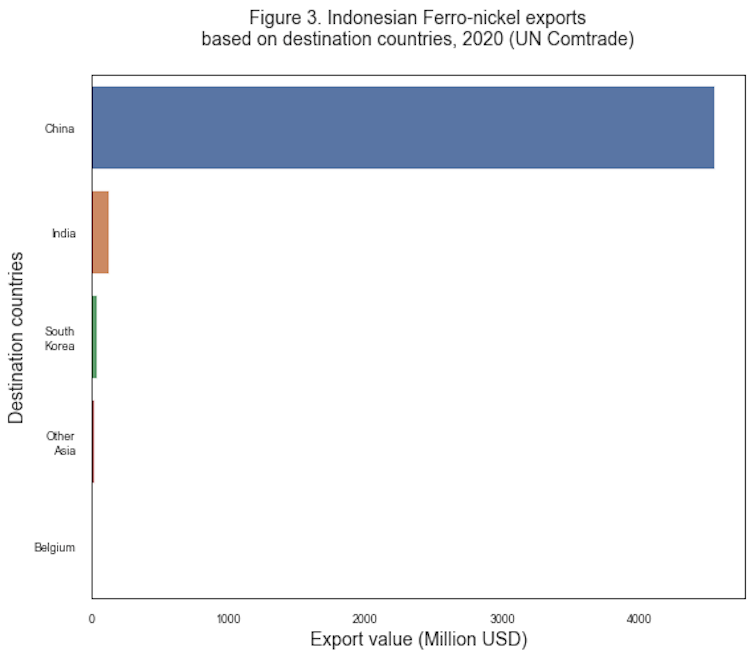

The government should also assess the alignment between the visions of this export ban and those who enjoy the benefit of the value addition. For example, Chinese-based companies chose to invest in Indonesia for the tax holidays offered and the access to cheap nickel but would export their production output back to China.

Figure 3 below illustrates the above case for ferronickel, a semi-finished commodity derived from smelting oxidised nickel ore.

The government needs a careful consideration

Tax holidays and guaranteed access to cheap nickel may distort the measurement of the economics of smelters. It is questionable whether smelters remain economically feasible if the government revokes all tax incentives and impose export duties on value-added nickel products to add to the state revenues.

This is without including the other problems, such as permit maladministration, increased energy demands, and environmental issues like water contamination, which have become an increasingly crucial aspect for global investors.

Not to mention, smelter operation requires 4.8 gigawatts of electricity annually. This runs counter to Indonesia’s spirit to cut carbon emissions in the following years.

More, Indonesia’s export ban has triggered a dispute filing by the European Union at the WTO. This suit is certainly not the best situation for Indonesia to start the term of its G20 presidency.

Suppose more countries join the European Union in this dispute. In that case, Indonesia is exposed to the risk of trade retaliation that will give the government a hard time when channelling its value-added nickel products to the global market. Indonesia’s appeal as a battery production center will no longer be enticing without the global market.

The ban has also caused Indonesia to miss out on gaining from the increased nickel price, which rose by five folds from February to early March because of the war between Russia and Ukraine, two major global nickel suppliers.

All in all, I view that the data the government used to support its claim of the success of the nickel export ban are weak. Potential tax losses, trade retaliations, and decreased mining revenues for only allowed selling to domestic companies under a lower pricing arrangement are significant issues in measuring the added value of export ban-based nickel downstreaming.

The government should measure the success based on more data, not only export data. The government must also integrate the calculations with its downstreaming roadmap to allow the creation of a long-term goal. On top of that, the government must disclose the data for the public to access.

If the current methodology is maintained, it may be best for us to remain sceptical of the benefits of export ban-based nickel downstreaming.

Krisna Gupta does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.