This story is published as part of a partnership between The Nation and the Texas Observer.

It’s a gloomy, overcast Sunday evening in August, and Albert Old Crow pulls a collapsible crate on wheels that held two giant CD binders from his maroon truck. Old Crow, 66, is host of the “Beyond Bows and Arrows” radio program in Dallas. He’s tall with long, graying hair tied into a low ponytail at the nape of his neck, dressed in a Head Start T-shirt and black basketball shorts, and holding a 44-ounce drink from Sonic. Old Crow, who is Cheyenne and originally from Hammon, Oklahoma, has brought hundreds of CDs with him to the KNON 89.3 FM station, as he’s done this every Sunday since October 1996.

“Beyond Bows and Arrows” has been on-air since the inception of the KNON radio station in 1983. The show was founded by volunteers, Frank McLemore and Dennis Wahkinney. At first, it was only 30 minutes long, and the hosts only had one cassette tape. Old Crow doesn’t remember what the first cassette was, but he says the second was a Chief Dan George album.

“My initial duty was to answer the phones, take requests,” Old Crow says. “Then, after a period of time to the microphone and eventually was introduced to working the board.”

Every Sunday, the show starts with the same song, “All My Relations” by Lisa Gerrard and Jeff Rona. The lyrics read: “To those who survived relocation, to the ones who died along the way, to those who carried on traditions and lived strong among their people, to those who left their communities by choice or by force.”

This rainy Sunday, Old Crow puts on his headphones, adjusts the sound board, clicks his mic on, and his warm voice enters homes, cars, and holding cells across the Dallas-Fort Worth area: “Alright, ladies and gentlemen, welcome to ‘Beyond Bows and Arrows,’ your weekly American Indian radio program brought to you every Sunday evening.”

The program is part of a long history of radio programs that were by Natives for Natives. Radio has long been an important resource for rural, Native American communities, utilized to disseminate essential information, create a sense of connection, and share culture and language. There are currently 60 Native-owned radio stations across the United States, according to Loris Taylor, CEO of Native Public Media. “The stations that we have are unique because when they’re tribally licensed, they amplify the voices of the community and that’s through song or music, through the art that they share,” Taylor says. One of them is KUEH 101.5, owned by Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo in El Paso. During the pandemic, the Pueblo used the station to broadcast their cultural events when large gatherings were prohibited.

Shows on non-Native owned radio stations provide a similar resource for the intertribal communities in major cities across the United States. Unlike Native-owned radio stations, which focus on one specific Indigenous community, urban Indigenous radio programs are intertribal and give space for many different Indigenous nations to be seen and heard. “Bows and Arrows” runs two hours of Native American music, banter, stories, and current events every Sunday evening. This show, the longest running Indigenous radio show in Texas, is for the Native American community of Dallas.

In 1941, Don Whistler, from the Sac and Fox Nation, started the “Indians for Indians Hour” at the WNAD radio station out of the University of Oklahoma. During the golden age of radio, the half-hour weekly program was one of the first radio shows that was meant for an Indigenous audience. Whistler even joked once that no white person would be allowed on the show. This during an era when Western radio shows like “Lone Ranger,” “Tales from the Texas Ranger,” and “Dr. Six-gun” were perpetuating racist stereotypes of Native Americans.

The show grew to nearly 75,000 listeners and was a pioneer in radio, which was, and remains, a predominantly white space. Whistler invited anyone or any group to perform on air. The program featured songs in Kiowa, Navajo, Apache, Comanche, Cheyenne, and many other languages.

When the National Congress of the American Indians began to organize and advocate for issues that were important to Indigenous communities like protecting tribal sovereignty, Whistler kept his listeners informed. It was a time when Indigenous children were placed in nearby boarding schools, economic pressures during World War II led many to move to cities for work, and in 1956, the Indian Relocation Act was passed.

“He was very well-versed in what was going on, both within Oklahoma, among different tribes, not just the Sac and Fox,” says Lina Ortega, an associate curator at OU’s Western History Collections. “He’s also well-aware of what was going on at the federal level because tribal leaders had to be. They needed to know what was going to impact their own nations and their own people.”

Listeners would send in telegrams and postcards to announce upcoming powwows and community events. Whistler, or Kesh-ke-kosh, the first elected principal chief for the Sac and Fox Nation, never centered himself in the show and would turn the mic over to others whenever possible, creating an intertribal space.

“It was a real model and, for that time, seems like a really vibrant space,” says Joshua Garrett-Davis, the author of Resounding Voices: Native Americans and Sound Media, 1890–1970. “In Native history, to the extent that the general public is familiar with in the 20th century, Native people are kind of invisible until the Alcatraz Occupation and the Red Power Movement. I think it’s important to acknowledge that a lot of political and cultural activism went on prior to that. This is one more example of that.”

Garrett-Davis spoke to Boyce Timmons, the successor to Whistler; he remembered that a Bureau of Indian Affairs agent in Anadarko, Oklahoma, once told him they rarely tried to do business on Tuesday afternoons because everyone was huddled around a radio listening to WNAD. In a couple of nearby boarding schools, the program was scheduled into the day allowing students to listen in; some even went to the radio station as a group to perform.

“It was a way to reconnect to their communities using that medium,” Garrett-Davis says.

McLemore and Wahkinney, founders of “Beyond Bows and Arrows,” were members of the Baha’i Faith. For the first five years of the show, Baha’i Faith members kept it on-air with their donations during the annual pledge drive. Eventually, Wahkinney started attending powwows and other events to garner more Indigenous listeners. It worked.

The show grew to an hour and then finally two hours. Old Crow was 41 when his voice first hit the airwaves of the Dallas-Fort Worth area. He remembers pulling up to an old, white, two-story residential home.“I think our radio equipment was holding it up,” Old Crow remembers, laughing. As soon as the station moved out, the house was torn down.

The radio station was on the second floor. Old Crow called the gaps in the wood floor their security system, because he could see from the second floor down to the first and watch who was coming and going. The floor was eventually covered with a rug after one volunteer said they felt like they were going to fall through.

“After about five years, Dennis started to back away from the radio show, because he saw that I was dependable and could run the board, take care of it, that I had the show’s best interests at heart, and so he just turned it over to me. So, we went from there,” Old Crow says. In the early 2000s, he took over the show and KNON moved into a new spot in far North Dallas.

The show is relaxed with a loose structure that changes from week to week. On this Sunday in August, the show begins with 10 minutes of music before Old Crow takes the mic. He talks about the rainy weather and how dark the studio is. Then, Old Crow passes the mic over to co-hosts Cory Werthen, who is non-Native, and Jessica Johnson, from the Chickasaw Nation, to introduce themselves.

“Mahli ishto’, we have a new weather word today guys, because it is storming outside,” Johnson says.

Old Crow plays “Stomp Dance,” led by John A. Gibson. “This is the only radio program in the Dallas-Fort Worth area where you can hear stomp music,” he says.

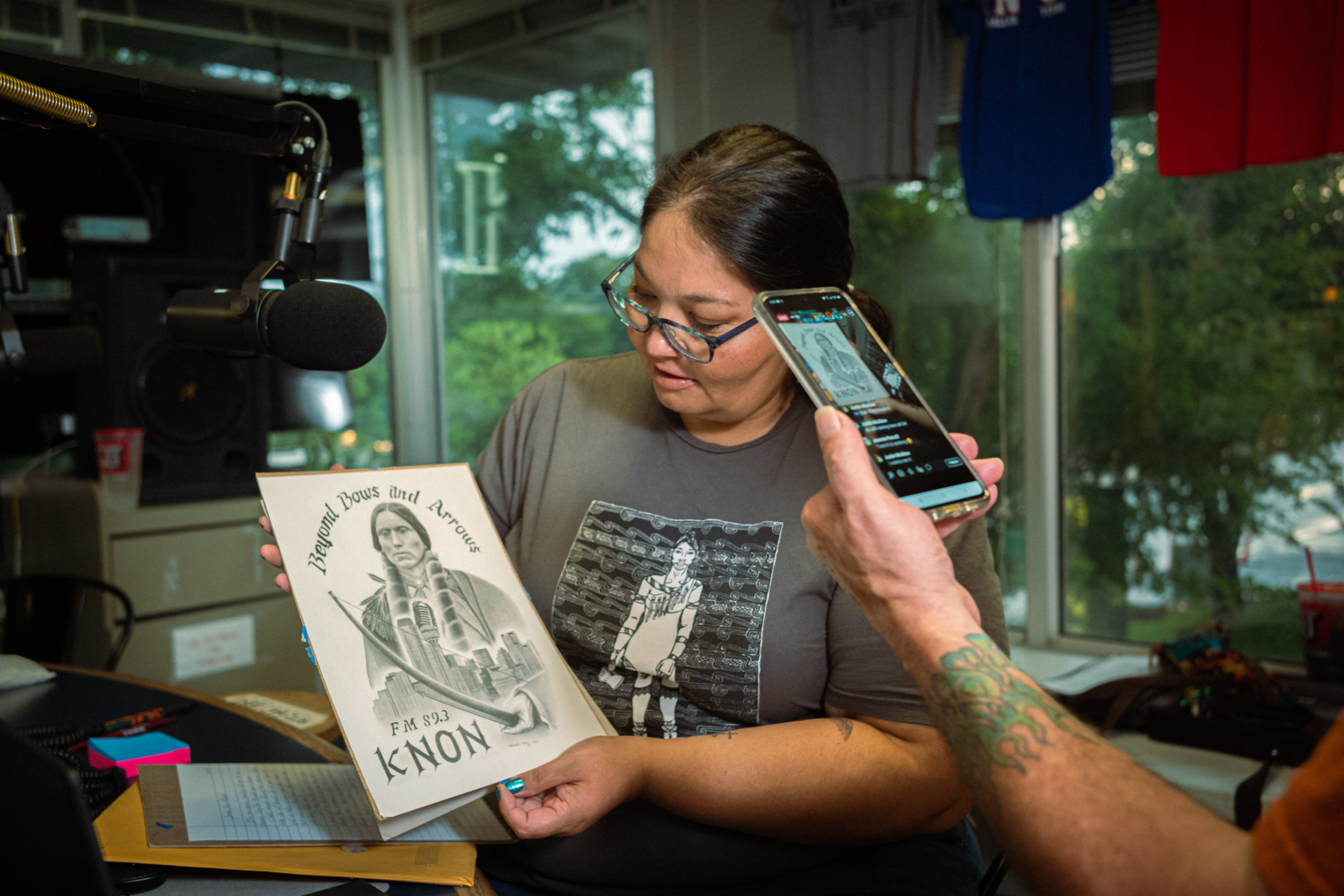

A longtime listener who is currently incarcerated at the Federal Correctional Institute in Seagoville, Texas, wrote a letter to the show. The writer sent a brief update and an illustration that will be the new logo for the program: a drawing of an Indigenous man looking off to the right; below him is the skyline of Dallas, with a microphone towering over the city. Overhead, it reads Beyond Bows and Arrows.

“It’s all good to listen to y’all on the radio, playing great tunes. It sure makes ya feel good. I appreciate what y’all are doing. Thank you,” Johnson reads out loud from the letter. The writer says that he’s been drawing and doing a lot of beadwork during the pandemic.

As Old Crow talks about the listeners who are currently incarcerated, he chokes up. Those listeners are the reason he keeps doing the show. “I gotta wipe my tears off. I was telling a story, and it touches my heart. It has to do with this radio show and the inmates at the federal facilities, male and female, Carswell, Fort Worth, Seagoville, how they listen to the show,” he says.

Old Crow explains how people who are incarcerated tell him how much the radio show means to them and how it keeps them out of trouble because they don’t want their radio privileges revoked. The show offers two hours every Sunday where they can feel connected to their own community and escape from their reality, he says. “What makes the radio station vital to this community, the Fort Worth people, [is] they can pick it up on their own individual radio and be in their own little space.”

Old Crow puts on his last couple songs for the transition to the next host, packs up his CD binders, grabs his Sonic drink, and leaves the studio.

Top Image: Jessica Johnson and Albert Oldcrow, two of the three hosts of Beyond Bows and Arrows, chat while off the air. By Ivan Armando Flores/ Texas Observer

Indigenous Affairs stories are produced with support from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.