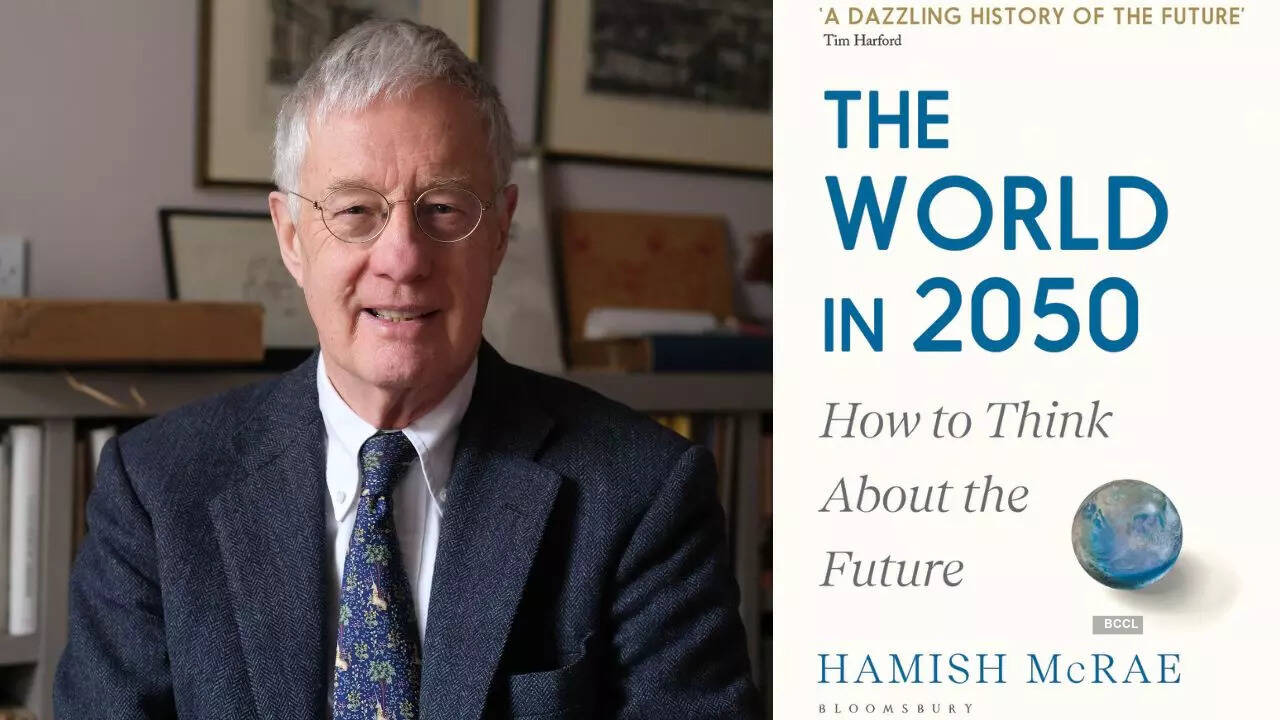

Renowned journalist Hamish McRae is considered as one of Europe's foremost voices about global trends in business, economics, and society. And now, in his latest book titled 'The World in 2050' he gives his insights about the next thirty years.

How will the world change and look like in 2050? What will happen to the environment, finance, governance and technology by then and how will it affect the global society? Answering some of these questions, McRae takes the readers on a journey to the future and what can one expect in the coming decades. "A bold and vital vision of our planet, 'The World in 2050' is an essential projection for anyone worried about what the future holds. For if we understand how our world is changing, we will be in a better position to secure our future in the decades to come," reads the book's blurb.

Read an exclusive excerpt from the book, published with the permission of Bloomsbury Publishing.

India and the Indian subcontinent – the exciting but bumpy ride ahead

India is as important to the world as China. As noted in the Introduction, at the time of the Roman Empire it was the world’s largest economy. In 1500 it was approximately the same size as China, and in 1820 it was still second only to it. So its position in 2050 as number three economy in the world, after China and the US, should really be seen as a natural and correct return of the country, and indeed the rest of the subcontinent, to its true status in the world. By 2100 I expect that its share of global GDP will have increased yet further.

To Indian nationalists this may sound triumphalist – India not just as number three to China and America, but probably larger than the European Union, too. For those of us who know and like India, and have witnessed its progress for many of its years as an independent nation, it is certainly a story of massive progress. That should be celebrated. But in that celebration it would be right to sound a note of caution, for the path to 2050 will be strewn with obstacles and dangers. India has to surmount these and be aware of the dangers. This journey will probably turn out fine, but it could conceivably turn out to be a disaster.

Four obstacles loom.

First, India has to improve its infrastructure. The need is widely accepted, with the contrast with China particularly evident. The scale of the challenge is enormous. Roads, water and sanitation, housing, commuter rail networks, hospitals, schools, telecom networks, healthcare, electricity supplies – the list goes on and on. Much progress has been made over the past thirty years, for people comparing India with China tend to underestimate how much has been achieved. That investment is continuing and by 2050 Indian infrastructure will be much better in every way. The question is whether it will be good enough to enable Indian people to be as competitive in their jobs and as happy in their home lives as they could and should be. The answer will be, for many people, not really. The wealthiest cities, including Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru (Bangalore), will be easier and more comfortable places

to live and work. Much of the countryside will lag behind. The progress will therefore be uneven and the question will be to what extent inadequate infrastructure holds back the spread of prosperity and the general levels of health and wellbeing. The answer to that depends on the gravity of and the response to the next challenge, the subcontinent’s environment.

Much of what happens to India’s environment is beyond the country’s control, for the subcontinent is particularly vulnerable to climate change. Rising sea levels threaten coastal communities, and though that should be manageable on a thirty-year time horizon, by 2050 large parts of cities such as Mumbai and Kolkata will be in danger. Perhaps even more serious, and certainly more immediate, will be rising temperatures because these will affect the entire subcontinent, not merely the coastal areas. Food production is particularly vulnerable, and India alone will be feeding more than 1.6 billion people. It is not helpful to predict catastrophic famines. It is, however, right to call for a thoughtful and measured response to minimise the dangers. By itself India can only have a marginal impact on climate change. But the most populous country in the world will have a special interest in leading the movement to try to hold down the pace at which carbon dioxide emissions climb.

It also has to tackle the things that are within its control, including land use, agricultural practices and, especially, water consumption. None of this will be easy, and a reasonable assumption must be that India faces a period of increasing economic and social disruption as a direct result of environmental pressures. Central government will be seen as failing, and people will turn to regional and local government for solutions. India will muddle through, but at a serious cost to human welfare.

The third obstacle is education. Middle-class lifestyles can only be supported by a skilled workforce. There will be no shortage of labour in India for at least the first half of this century, but that steady supply of young people entering the workforce every year needs jobs. India can only create those fast enough if it educates its workforce better, for the job opportunities are for the skilled. The young people of India’s huge middle class are competing in global markets against their peers around the globe. So they must be competitive if they are not to be disappointed, and find themselves in dead-end jobs. India’s education system has pinnacles of excellence, but too many mediocre performers at lower levels. It is a mammoth challenge.

Finally, and associated with education, if India is to have a harmonious future it will have to tackle inequality. It is gradually doing so, and probably does not receive sufficient credit for that. Indian society is helped by the ways in which its families, especially poorer ones, support each other through difficult times. The safety net is family, not the state. Overall wealth will rise and it is reasonable to expect that by 2050 more than half the country will be middle class. That is enormously welcome, of course, but it will make harsher the gap between these newly comfortable families and those that are left behind. Central government will not manage this well. It can’t. Top-down social welfare policies, even if affordable, are impossible to administer across a nation of more than 1.6 billion people. So state and local governments will step in, or at least be under political pressure to do so. As noted in Chapter 1 some states are vastly wealthier than others, with the effect that different levels of wealth and inequality will tend to drive the country apart. India will hold together as a country, but the effectiveness or otherwise of the way it tackles inequalities will be one of the factors that will determine how loose or how strong the glue that holds it together will be.

The dangers: there are three obvious ones, as well as more that we cannot yet see.

The first two pull against each other and it is not clear which is more likely to dominate. One is fragmentation, the other nationalism. Unless there is some catastrophe India will retain its territorial integrity. But it is likely to become a looser federation of states as their interests diverge. This will have to be managed and there is plenty of potential for miscalculation. Countering this will be Hindu nationalism, a single identity imposed from on top. Currently nationalism is the prevailing force, and it is quite possible that it will remain so through much of the 2020s and beyond. But at some stage the wind may shift and nationalism be pushed aside by regionalism. While no one can hope to call how this tussle will be resolved, there is a real danger that it might break out into active internal conflict. It is a profoundly uncomfortable possibility.

The third danger is an external conflict that escalates into war. It makes no sense to predict war. All we can do is to observe the tensions between India and its two great neighbours, China and Pakistan. Those tensions have risen and fallen over the past seventy or so years. The balance of probability is that they will continue to do just that: periods of near-open conflict, three nuclear-armed powers that periodically assert their political positions by initiating modest clashes but never using anything like their full conventional arsenal, let alone using nuclear weapons. For there to be a nuclear war over what would in the broader scheme of things be a quite small territorial dispute is mercifully not only utterly irrational; it is almost unthinkable.

However, the unthinkable, the unbearable, can occur. The history of the twentieth century tells us that. We can make judgements about the likelihood of catastrophe; my point here is simply to acknowledge the possible outcomes, however unlikely I think they may be. India and China will inevitably be rivals. In a sense they should be rivals. For centuries they were unquestionably the two largest economies and arguably the two greatest civilisations on earth. In the next thirty years that relationship to some extent resumes – the largest and the third largest economies. We, and they, have to rely on the judgement of their leadership to ensure that the reasonable working relationship that has characterised their dealings over the past centuries continues through this one.