A for appam, B for bonda, and C for chaat…If we had to teach our children the ABCs of food, I’d rather opt for something like this and not A for asparagus, B for burger and C for cookie.

As parents and teachers introduce books about food to children, more often than not, they borrow from Western concepts. Be it ingredients, dishes, or even food etiquette, rarely have we found books that highlight traditional Indian delicacies and practices. It is only over the last couple of years that Indian publishers have delved into India’s rich culinary diversity to bring out interactive and engaging titles for children.

Chitwan Mittal, founder-director of Gurgaon-based AdiDev Press — the publication house behind books such as J for Jalebi — says in many ways, it is only now that Indian children’s publishing is coming into its own. “For a long time, Western children’s books dominated Indian bookstores, but there has been a clear shift in what the market wants, which is representation and stories rooted in Indian culture and practices,” says Chitwan.

Perhaps this is why most children are drawn to the kitchen: playing with vessels, and imitating cooking. “For parents as well, food is a way of showcasing their culture and celebrating where they come from. There’s certainly a space here to tell interesting stories that can celebrate parents’ nostalgia for their childhood while introducing young readers to their roots,” she says.

This year, Chitwan will launch a board book in rhyme that features iconic Indian foods and cities. “It approaches numbers and counting using Indian food as a theme. The book manages to incorporate a lot of different regional foods that we feel don’t get represented enough.”

The food debate

So why has it taken Indian publishing a long time to adapt from Indian kitchens?

Sayoni Basu, consultant, Duckbill Books (a part of Penguin Random House), explains how one needs to look at the status that English has in our country to understand the phenomenon. “While there are many families which are effectively bilingual or trilingual, for many first-generation or second-generation speakers, English remains a language of aspiration. And therefore there is a certain skepticism about ‘Indian English’, a belief that somehow ‘foreign English’ is purer and better,” she says, adding how this is easily reflected in the fact that international books often outsell Indian ones, regardless of quality “even when there are equally good if not better Indian titles for the same age group and genre”. Sayoni adds, “And B for burger and C for cookie are equally Indian, would you not say? At least in urban India.”

While this may be unfortunately true, the onus lies on parents, caregivers, and schools to bring the spotlight back on our everyday foods and lesser-known Indian delicacies. And Indian authors have found interesting ways to make books more accessible.

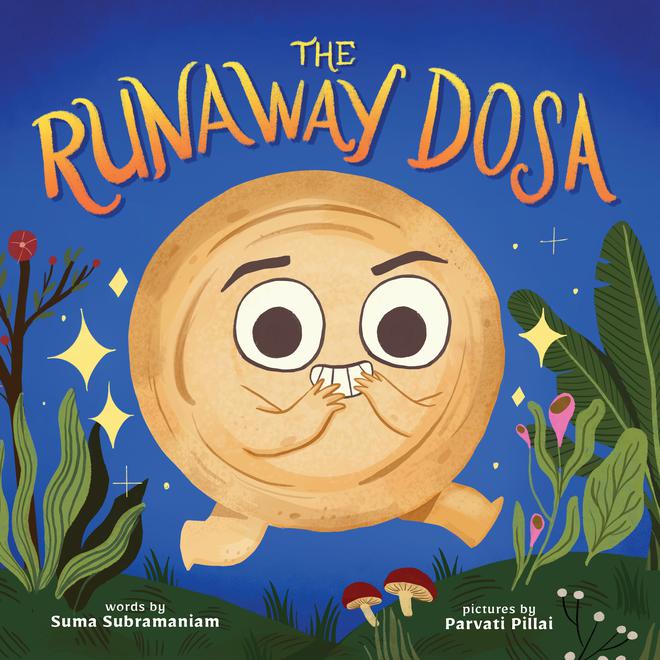

Suma Subramaniam, author of popular book The Runaway Dosa (Little Bee Books), says as a child, she never saw books featuring Indian food “even if that’s what I ate at home every day”. “As an adult, the landscape hadn’t changed much. So I realise that my subconscious quest for identity began decades ago,” says the author whose book themed on the dosa drew inspiration from The Gingerbread Man and the all-time favorite Tamil rhyme, ‘Dosai! Amma, Dosai’.

Another popular book themed on this rhyme is Dosa Amma Dosa by Anupama S Iyer (Tulika). “The book not only connected with children but also with parents and family who would have heard the rhyme and enjoyed it in their childhood. Second, the brightly coloured characters depicted as Channapatna toys worked well with the rhyme, and lent it a playful spin.” The latter, Anupama explains, was a deliberate decision to help promote local handicraft rather than imported, plastic toys. Most importantly, the editorial choices in the book, particularly that it does not say who made the dosa like in the Tamil rhyme (where it says amma made the dosas), but that the dosas were made, was a refreshing change, adds Anupama, who is currently a freelance design consultant based in London.

Suma’s short story in The Hero Next Door (Penguin Random House) also mentions masala dosas as well as snacks like murukku and ribbon pakoda. “My forthcoming middle-grade books, V. Malar: Greatest Host Of All Time and V. Malar: Greatest Ranger Of All Time (Candlewick), illustrated by Archana Sreenivasan, also have Indian food in them like murukku, badam paal, bajji, jaggery, kootu, paruthi paal (cottonseed milk), pongal, vada, idli, and moongil arisi kanji (bamboo rice porridge),” says Suma whose upcoming picture book, My Name Is Long As A River, highlights Ashoka halwa.

Popular themes and sub-genres

Food as a subject marks an instant connection with children, and has proven to be an effective tool to teach emotions too. For instance, in Paati’s Rasam (Karadi Tales), young Malli grapples with the loss of her grandmother and recreates her favourite rasam. In Andaleeb Wajid’s Mirror Mirror, which is about body dysmorphia, the girl’s relationship with her body is negotiated through food and cooking.

In Bijal Vachharajani’s Savi and the Memory Keeper (Hachette), food becomes a way for a grieving family to relive memories. “Food in literature often works to bring together different characters and celebrate diversity. Humour and food, festivals and food, mysteries and food are some of the popular themes in children’s literature as well. The other books we find that are very popular are the books on food and sustainability. Apart from that, food becomes a way of bashing gender stereotypes in the kitchen and at the dining table,” explains Bijal, commissioning editor, Pratham Books.

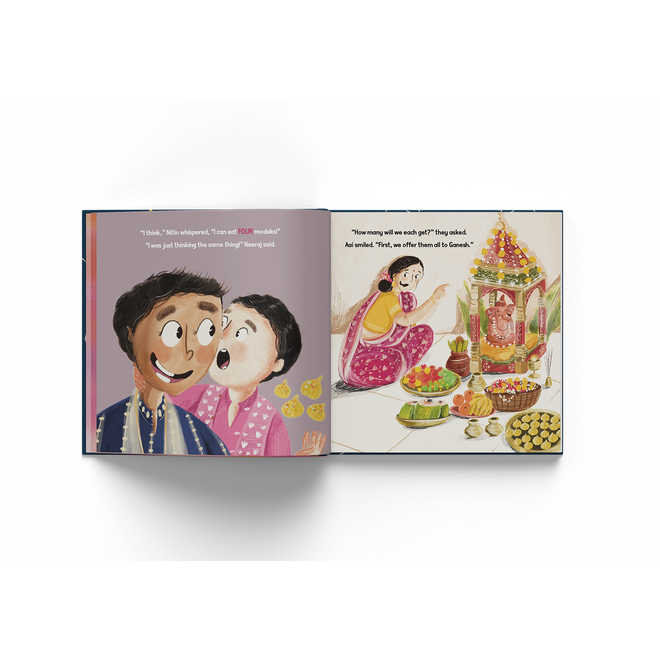

“While there may be non-fiction books about different types of food or recipes and cooking, food can also be introduced as a theme or as a hook in an interesting way in fictional books,” says Chitwan, who highlights how in the picture book 21 Modaks for Ganesh Chaturthi (Nandini Nayar) foods associated with the festival have been used as an entry point to get children interested in the story behind the festival. ”By putting our characters’ love of modaks at the centre, we create an immediate connection with the reader. With that hook in place, we then get into the story of our two young protagonists, Neeraj and Nitin, and how they spend their day helping their parents prepare to celebrate the festival.”

Sheena Garg, who founded publishing house Haathi Tales in 2021, says ABCs or A to Z remains the most popular way to introduce new or unfamiliar Indian foods and words to children. “Simple stories where children cook something with a parent or a grandparent, and learn the process of cooking something new while connecting with their culture and traditions would be the next most popular theme,” says the author of Gapagap, a picture book all about rotis.

Even internationally, authors from the Indian diaspora “who understand the value of exposing their kids to Indian foods have published several such books”, she adds. These include A Very Asian Guide to Indian Food by Julie Ajinkya, and Masala Chai Fast and Slow by Rajana LaRocca, to name a few.

Regional languages

Research also shows that learning to read in the mother tongue can make education engaging for children and reduce dropout rates in schools. And what better way than to use food as a hook? “The power of language to make connections, forge relationships with the story, and conjure up the meaning of the words is exceptional. It makes reading more joyful, and also more accessible, and opens new worlds to them, all in a language that they intimately know and understand,” says Bijal, adding that all their books are translated in five languages at least.

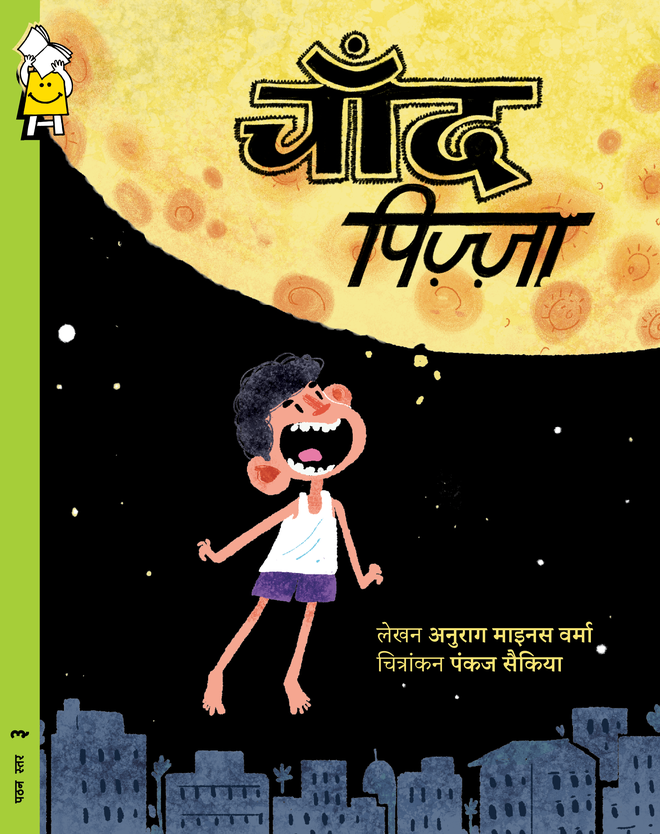

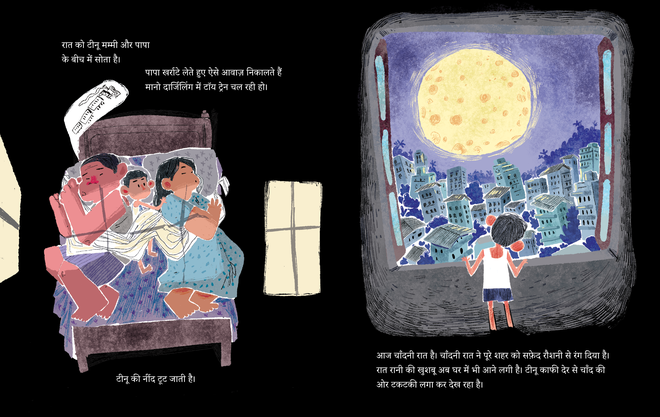

Ek Hoti Idly (based on a Marathi rhyme), and Chaand Pizza are upcoming titles at Pratham Books, and the publication house’s free online platform Storyweaver is home to 350 languages: Indian, international, endangered, indigenous. Anurag Minus Verma, New Delhi-based multimedia artist, and author of Chaand Pizza, says books in one’s mother tongue enhance the relatability of the story for children “The use of local language has an immediate impact, as children don’t have to go through the process of mentally translating the text. Additionally, subtle jokes and colloquial expressions often work more effectively in local languages,” he says.

The gap

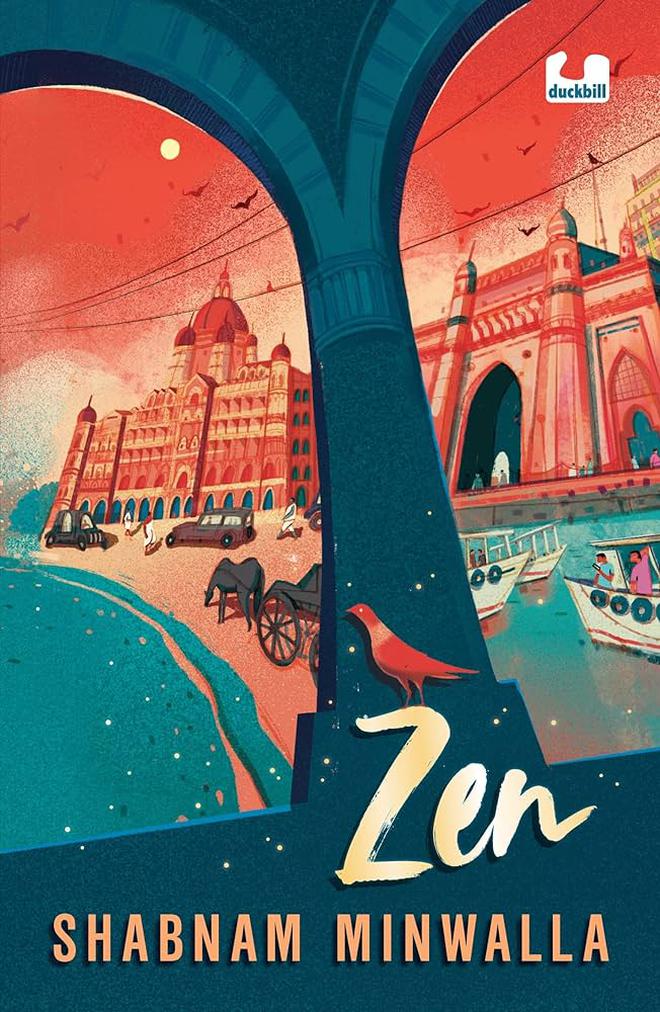

While Sayoni sees a rising popularity for books for children and young adults, and more diversity in themes, food-centric books are yet to catch up. “Food is such an integral part of the human experience that it often plays an important role in books which are not about food, so to speak. In Shabnam Minwalla’s Zen, for example, the romance of the contemporary couple starts with an altercation about food and carries on through Swiggy deliveries,” she says, adding how Hannah Lalhanpuii’s Postcard from the Lushai Brigade, looks at the nameless protagonist’s longing for home and stability manifesting in dreams of chicken roasting over the fire at arkaiden zan with his brother.

“In my experience, I’ve seen a lot of middle-grade books that touch upon food, many more so than Young Adult (YA), which is quite a small segment of Indian children’s publishing in any case. Where I do see a gap is in books that feature Indian food for emerging readers, i.e., children between 0 and eight years of age,” explains Chitwan.

And even writing for children is not as simple as it may seem. Anurag, who has written fiction and poetry books before, Chaand Pizza is his first title exclusively for children. “I thought children’s writing might be ‘simple’ writing. However, as I started reading more and delving into the world of children’s writing, I discovered that it hides a lot of complexity beneath its seemingly simple surface. In fact, children’s writing is closer to poetry, as it encompasses elements of wonder, amusement, beauty, magic realism, and even surrealism. Combining all these elements and yet making it accessible and interesting is quite challenging.”

He adds that each generation of children sees the world through a different lens, and this underscores the importance of incorporating contemporary symbols, ideas, and trends in modern children’s literature to create compelling stories. “The motif of food is particularly significant, serving as a sensory experience that can evoke both the present and memories,” explains Anurag, who believes mentioning specific foods adds depth to the narrative, pulling the reader into the story. “Through the use of this motif, many interesting narratives can be incorporated, as food often conceals aspects not just of joy but also of history, society, national identity, and personal memories. More exploration of food from different angles has yet to take off in children’s literature. The possibilities of stories in this realm are endless,” he concludes.