It is a truth universally acknowledged that readers don’t like to be interrupted. “They like to read and lose themselves in a book in companionable silence,” says Rachana Malhotra of Juhu Reads, a chapter of a pan-India community of bibliophiles who have turned reading books in natural surroundings such as parks and beaches into a weekly ritual. “Here, there is no compulsion for small talk, but there is a sense of safety. Like in your childhood, when you could get lost in your book.”

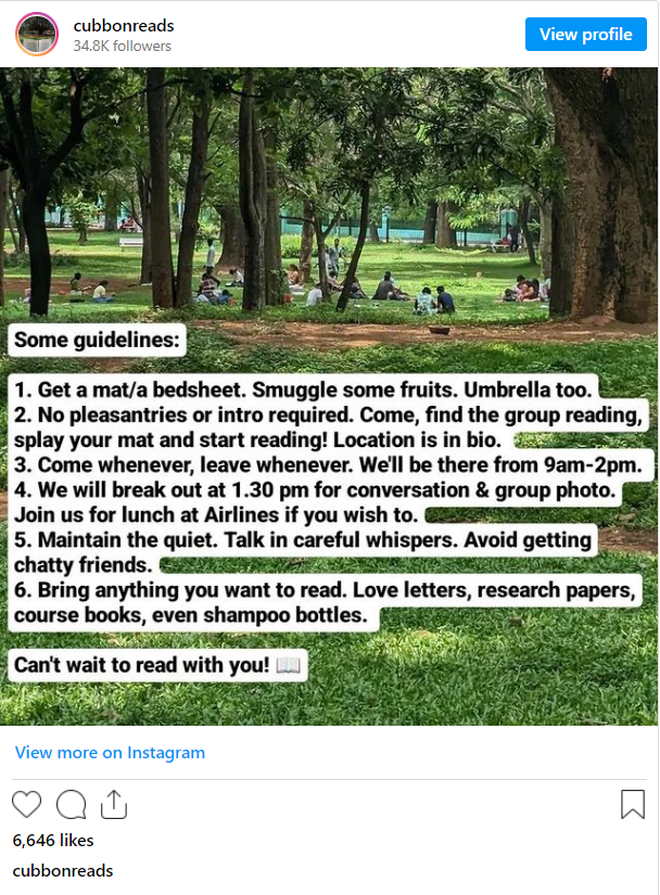

We’ve often imagined going to a public park with a mat, laying it on the ground, stretching out and reading a book. But in India, it was unimaginable for most people that they could turn off the safety switch in public spaces. It is happening now, however, thanks to weekly reading sessions coordinated through social media. The time and location are shared through Instagram accounts handled by curators — the chapters named eponymously after the parks or locations where they meet weekly — and people show up.

The genesis of everything

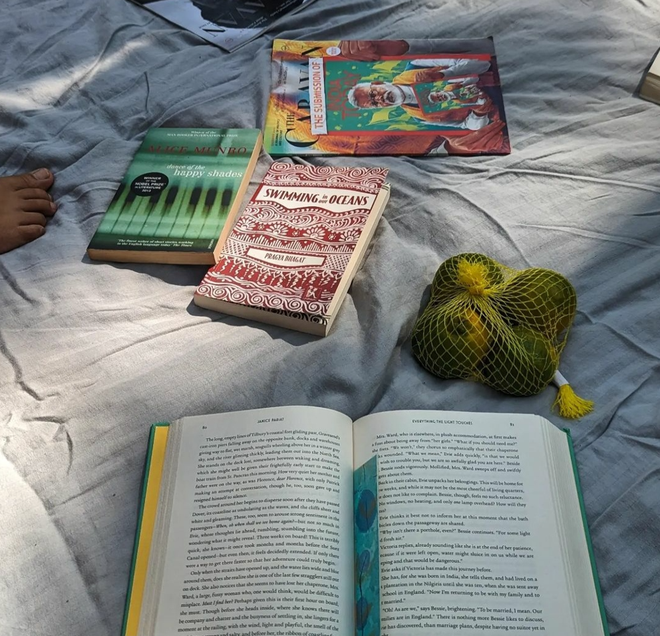

The reading revolution that is unfolding across open spaces in the country began in Bengaluru. On January 7, 2023, entrepreneur Harsh Snehanshu, 33, and his friend Shruti Sah, 30, a baker, created the Instagram handle @cubbonreads. They posted a photograph of an open book (Janice Pariat’s Everything the Light Touches) backdropped by a large tree in Cubbon Park, with a message: “The old wise tree. Or the old wise book? Find us with books and fruits, next to this tree, every Saturday! Message us if you need the pin drop.”

Six people turned up on the first Saturday, on January 14. Tackling traffic and getting to the park was a problem. “I wish I was near that place somewhere,” was one of the comments. Then on January 28, there were only three readers: Snehanshu, Sah, and a man named Sandeep who dropped by. It appeared as if book reading was just an aspirational thing and nobody was willing to take time out to read.

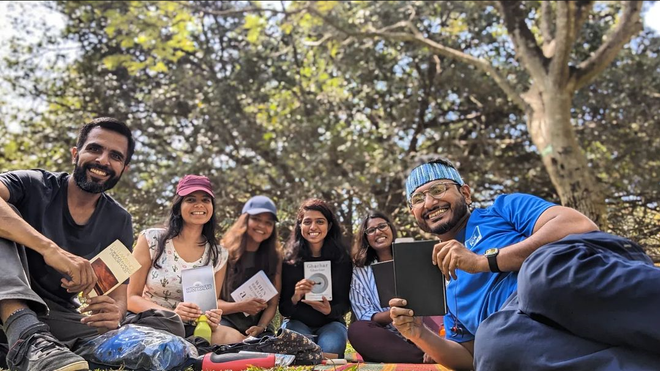

But as the weeks passed, three became 30. A recent Cubbon Reads gathering saw 300 people turn up! “Both Shruti and I love reading and used to spend hours in parks reading. I was in Paris where people always had books in their hands, while in Shanghai people were lost in their screens,” reminisces Snehanshu. “I thought I should share my thoughts.”

Over the past few months, over 60 chapters have popped up all over the country and even abroad, with a hat tip to Cubbon Reads, which marked 25 weeks with a turnout of hundreds. “I thought it would be great if we can get 10,000 people to come to the park to lose themselves in reading for the first anniversary. Guess what, that looks easily doable!” says Snehanshu.

Men, women, families with children, and people of all ages and identities pop by with a mat, a book, a bottle of water, and sometimes a plate of cookies or a bag of oranges. They pile their books, occasionally pose for a photograph, and then they read. On a sandy beach in Chennai, in a park in Pune, under an arbour in Mumbai, in the precinct of the Thrissur Pooram, under the Bara Gumbad of Lodhi Garden in Delhi, and across a rapidly increasing count of parks and gardens. It looks like an Enid Blyton picnic come to life minus the currant buns and potted meat sandwiches.

While Harsh Snehanshu and Gautam Krishna are among the few male curators, most of the reading communities have women curators. “One of the guidelines we got from Cubbon Reads was to have women curators to bring a sense of safety,” says Diya Sengupta, a writer and editor who co-curates Juhu Reads.

A boon for lonely hearts

The movement is also an instance of Indians reclaiming their public spaces — much like the night walks being organised by women in Noida or the biking excursions in Mumbai. “There are people who write letters, crochet, indulge in creative writing or finishing their research work. It is sharing human warmth without being gawked at. People who opt to stay out of the grid still like human company,” says Snehanshu. He considers what’s happening as silent activism to take back a city’s open spaces.

“Book reading or community reading is literally like a balm,” says Ayman Ali Khan, a behavioural psychotherapist, giving an insight into how the reading sessions have spread so quickly across Indian cities. “It is a healthy coping mechanism as people seek different forms of connections when they step out.” Silent reading groups are also in keeping with mindful practices that many are incorporating into their lives. And it is ideal for everyone, including the introverted, as they get a chance to join in and experience a sense of community without the pressure of interacting with anyone.

While the larger metros such as Bengaluru, Mumbai and Delhi have multiple chapters, the #silentreading movement has reached smaller cities such as Kochi, Pune, Pondicherry, and Dehradun. The Thrissur chapter is only three weeks old and on July 1, the turnout was 40 people. “A lot of children came. I was not expecting that,” says Gautham Krishna, the curator of @thrissureads, which meets on Saturday mornings at Thekkinkaadu Maithanam, at the centre of the busy city. “Earlier I would go to book reading sessions and there would be conversation, discussion and then heated political debate. This silent reading initiative lets people just read and that is a very good thing.”

Internationally, there are over 15 chapters, including Boston and San Jose in the U.S., London, Paris and Johannesburg.

Spin-offs from Cubbon

From six years to 70

Ritika Chawla, 30, a friend of Snehanshu’s, started Lodhi Reads in Delhi in May. Snehanshu turned up soon after at the 90-acre park with a mat. “Lodhi Garden is an open space that is centrally located and well connected. Earlier, people would come to exercise, do yoga and walk. But reading in the shade of a tree is better,” says Chawla, who curates the Delhi chapter along with Nabiha Tasnim, 27. Sixty people turned up on June 25. “You can socialise at the end or you can just walk away. Readers want to interact, but on their own terms. Now there is a growing sense of community.” The open space, she adds, is calming and occasionally local dogs come over and get comfortable on their mats. Occasionally, the chaiwalla, who spots a business opportunity, turns up with a kettle.

Of course, the communities are met with a lot of curiosity, too. “Ye log sab yahan padhai karre [all these people are studying here],” commented a young boy when he encountered the chapter in Mumbai’s Kaifi Azmi Park. “There are a lot of queries from strangers who want to know what is happening. Why are people sitting away from each other but doing a similar activity? We explain to them,” says Diya Sengupta, one of the three curators of Juhu Reads. “We were recently joined by a man on a wheelchair accompanied by his wife. He promised to come again, and sure enough he turned up at the latest edition.”

There is no real demographic when it comes to the people turning up. Sah recalls a 70-year-old man reading at Cubbon Park, while at Hyderabad’s Kasu Brahmananda Reddy Park, Rishika, 6, and Saanvi, 5, enjoy turning up with their books. “If they begin young, they will retain their love for books,” says Rayappa Maykuntala, a techie, who tags along with his two nieces with a book of his own. “Children emulate what they see. You cannot hold a phone and ask them to read books.” The young girls soon want water, then a bite, and then answers to their questions. Their reading session winds up in a short time, but the connection made will last much longer.

Chapter curators share how some readers get together at the end of a session, chat, and even head out for a meal. Bessy Reads in Chennai occasionally ends their community reading at Besant Nagar beach with a hot breakfast at Murugan Idli Shop down the road.

Harshita Soni — who teaches yoga and believes “we need a community of people to sustain our practice” — often joins Hyderabad Reads. “It’s just me, my books and nature. I am able to sit and read for an hour and a half without being too distracted. It’s a great mindfulness practice. Only after it closes [around 6.45 p.m.] do some people stay and talk about the book they read. So I learn about other authors.”

Start of a reading revolution

While Silent Book Clubs have been around for more than a decade with somewhat similar rules and goals, the movement triggered by Cubbon Reads is riding the wave of Instagram. And as such, the communities do not look down on smartphones or newer ways of ‘reading’ at their gatherings. E-readers are a fixture most weekends, and a few people have turned up only to plug in their earphones, settle down under a tree, and listen to audio books.

“You promote reading that’s open to all, to encourage anyone,” says Shreya, who came to Hyderabad Reads and learnt about a new chapter planned at the Biodiversity Garden, which is closer to where she lives. “This is one of the times I step out of my home.”

This isn’t a book club

The reading revolution is also going hand-in-hand with a publishing one. “The number of readers increased after the COVID lockdowns, and book sales have gone up by 30%-40%, with young adult fiction leading the pack,” says Mayi Gowda of Blossoms in Bengaluru, who recently opened another outlet to cater to the demand. The bookseller is aware of the outdoor reading communities and adds that “we have GenZ filling the shop” since last year and the trend is continuing in 2023. The reading revolution is also going hand-in-hand with a publishing one. “The number of readers increased after the COVID lockdowns, and book sales have gone up by 30%-40%, with young adult fiction leading the pack,” says Mayi Gowda of Blossoms in Bengaluru, who recently opened another outlet to cater to the demand. The bookseller is aware of the outdoor reading communities and adds that “we have GenZ filling the shop” since last year and the trend is continuing in 2023.

In Hyderabad, when indie book store Luna opened in October, “we didn’t expect a great response. But now we have been overwhelmed. A majority of buyers are young readers who spend hours browsing before buying books,” says owner Swapna Sudhakar, on a Sunday afternoon as buyers/readers explored the duplex house converted into a shop in upscale Jubilee Hills.

Publishing is one of the few industries in India that is growing at a 6% compounded annual growth rate, according to industry data. The country is expected to have over 439 million readers by 2027 (which is larger than the population of the US), and community reading initiatives will only add to this. Perhaps this is the dawn of a new age of reading.

With inputs from Neha Mehrotra