In 2018, Chinese engineers became the first to link the scattered islands of the Maldives by road, inaugurating the 2km Sinamalé Bridge that arched across the waters separating the capital Malé from its airport.

The inter-island bridge was a symbol of Beijing’s multibillion-dollar infrastructure lending programme in the Indian Ocean. Now, another regional power is preparing to bankroll its own, even longer, structure in the same area.

With loans and grants, India is funding the $500mn “Greater Malé Connectivity Project”, a 7km bridge linking the capital to several other surrounding islands, in a project run by India’s historic Shapoorji Pallonji Group conglomerate.

This battle of the bridges in the picturesque island chain is one of the clearest examples of a tussle for geoeconomic influence between Beijing and New Delhi.

As China’s Belt and Road Initiative projects proliferated in south Asia and the Indian Ocean, so too has Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s India ramped up its own infrastructure lending in the region.

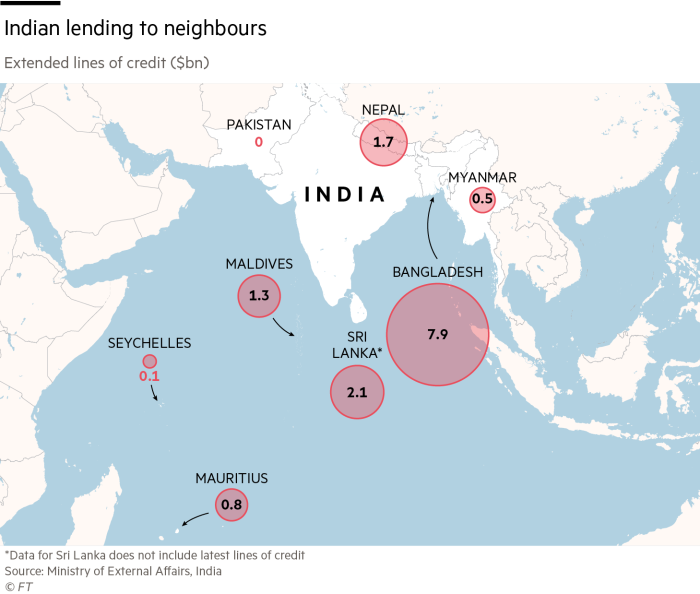

While India lags far behind China in its overseas lending, New Delhi has stepped up its efforts in recent years, providing tens of billions of dollars in credit to neighbouring countries, including financially distressed BRI-recipients like Sri Lanka. Indian companies have also expanded rapidly in the region, providing a counterweight to Chinese commercial activity.

Modi’s government “began to develop this sense that India needs to do something,” says C Raja Mohan, a senior fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute in Delhi. “It has been far more alive to the geopolitical contestation with China.”

India’s role as a creditor has grown fast. Lending through India’s development partnership administration, by which it offers other governments lines of credit, has nearly tripled in value since Modi came to office in 2014 compared to the previous eight-year period, according to the foreign ministry, totalling $32.5bn.

India’s cumulative “development assistance” since its independence in 1947 has nearly doubled from $55bn to $107bn since 2014, according to the government-backed RIS think-tank.

The scale is far below what China is attempting through the BRI launched nine years ago, which the American Enterprise Institute think-tank estimates reached $838bn last year.

Yet the foreign ministry said India has extended more than 300 lines of credit for around 600 projects, ranging from a cement factory in Djibouti to the Maldivian bridge. India has also funded everything from training courses to restoring overseas cultural sites such as mosques and temples.

India doesn’t have the capability to scale up to the extent of Belt and Road, Mohan says. “But it’s doing things, within its scope, where it’s offering some competition to China.”

Although India, with 1.4bn people, is soon to overtake China as the world’s largest country by population, its economy remains about a fifth of the size. Within its own backyard of south Asia, however, it is a colossus that overwhelms its neighbours in scale and economic activity.

Indian policymakers see countering BRI as vital to avoid being surrounded by pro-Chinese governments and infrastructure they speculate could one day serve Beijing’s military interests. India and China have fought multiple conflicts over decades, most recently a deadly clash on their Himalayan border in 2020.

An analysis published last year by the AidData lab at William & Mary college found that India’s state-owned ExIm Bank, which provides the overseas credit, was “significantly more likely” to finance projects in a country if the Chinese government had provided finance there within the previous year. It added that this dynamic was even stronger where China had made “public opinion gains relative to India”.

But this push is not coming from the public sector alone. While India’s state-owned companies have long operated in neighbouring countries, analysts say Modi’s government has realised it needs more corporate economic firepower than they can provide.

India has used a mixture of policy and diplomacy, they say, to encourage private corporate champions to pursue deals that offer commercial opportunities in fast-growing markets and help advance New Delhi’s interests.

In recent years, conglomerates such as the Adani Group, run by the world’s third-richest man Gautam Adani, who is a vocal advocate for Modi’s government, have expanded into power and infrastructure projects everywhere from Myanmar to Sri Lanka.

Modi’s government “wants to do big stuff and it doesn’t think that the Indian public sector is up to it”, says Kanti Bajpai, a political scientist at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore. “Most Indian businesses are too conservative. It needs an Adani.”

Better thy neighbour

India publicly plays down the competition with China. “We’d like to see our neighbours prosper. South-south co-operation is a big part of our foreign policy,” says Prabhat Kumar, an Indian foreign ministry official who oversees development partnerships. “The global south matters to us, and we’ve been doing this for a long time. It’s not reactive.”

Yet under Modi it has also framed its development finance in terms designed to contrast with Chinese lending practices, which it portrays as predatory.

While inaugurating housing and solar power projects in Mauritius earlier this year, Modi said Indian lending is “based on the needs and priorities of our partners and respects their sovereignty.” He has also criticised efforts to create colonial “dependence partnerships”.

New Delhi’s role as a regional lender has come into focus over the past year as the surge in global inflation and a historically strong dollar tipped several of its neighbours into financial trouble.

Nowhere was this more acute than in Sri Lanka, which in May became the first Asia-Pacific country to go bankrupt in two decades after effectively running out of foreign reserves.

As an economic meltdown left the island of 22mn with shortages of everyday basics, India provided nearly $4bn in loans and grants for supplies of fuel, medicine and other food, according to the foreign ministry.

China has also provided food aid and financial assistance worth at least $1.2bn, according to Sri Lanka’s envoy in Beijing. But it had previously resisted Sri Lanka’s requests to restructure its loans, which total around $7bn.

Critics say that Sri Lanka’s debt crisis was exacerbated by BRI loans for projects that failed to generate returns, such as the enormous but underutilised Hambantota port which was in 2017 handed over to Beijing on a 99-year lease.

A study this month from Johns Hopkins’ China Africa Research Initiative found that Indian credit to Sri Lanka had lower effective interest rates, at around 1 per cent in 2021, than Chinese loans at 3.2 per cent.

India’s own anxieties about BRI were compounded this year when, against its objections, Sri Lankan authorities allowed a Chinese military surveillance ship to dock at the island’s Hambantota port. Indian officials warned the vessel could be used to spy on New Delhi’s military installations.

So it has begun pushing back in a region where it holds significant sway. Earlier this year, New Delhi won a trio of energy projects in northern Sri Lanka previously held by a Chinese developer, after lobbying the Sri Lanka government against the deal over “security” concerns sparked by its proximity to India’s coast.

Companies like Adani have also won a number of important infrastructure contracts this year and in September the island’s president Ranil Wickremesinghe publicly instructed his officials to “resolve the obstacles” to Indian-backed projects.

But while India presents its own lending as a benevolent alternative to China, those living in the neighbourhood do not always see it that way.

In the Maldives, for example, opposition leaders have fuelled an “India Out” campaign, alleging that Indian-funded projects in the archipelago are a cover to give New Delhi a military foothold.

“It’s like what China does,” said one south Asian diplomat. “Everywhere that China is, they are also there doing something to get a foothold.”

Lifting up south Asia

Historically, New Delhi has had two overarching reasons to spend its limited resources overseas: to increase soft power through development assistance and fund infrastructure crucial for regional trade, like ports.

State-owned Indian energy companies have for years worked on hydropower projects in smaller neighbours like Nepal, while India spent $3bn on projects in Afghanistan, in an effort to counteract Pakistani influence in the country.

India eventually launched a line-of-credit programme. Yet, with the country struggling with its own widespread poverty and severe domestic infrastructure deficit, such initiatives were comparatively modest. For much of its history, India was a large recipient of foreign aid.

The lack of investment in south Asia’s ports, railways and other trade-enabling infrastructure helps explain why it remains one of the world’s least integrated regions. Intra-regional trade accounts for only 5 per cent of total trade, according to the World Bank, with the animosity between India and Pakistan further stymying activity.

Analysts say improving regional connectivity is a clear necessity for India to boost its own growth.

For example, while New Delhi has in total extended lines of credit worth nearly $8bn to Bangladesh, this includes helping to fund the construction of cross-country transportation networks that will improve links between India’s remote north-east and the rest of the country via Bangladesh.

Yet India’s efforts acquired added urgency after Beijing responded to the lack of investment in the region by pouring billions of dollars into India’s neighbours through BRI.

“Even if China did not exist, India would still be doing most of it,” says Constantino Xavier, a fellow at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress. “Not all of it, not that fast, and not with the political importance . . . [but] the private sector is saying that we need the basic infrastructure to trade with our neighbouring countries, and the world.”

Enter the private sector

To enlist companies in its overseas push, Modi’s government in 2015 launched a scheme offering concessional loans for “strategically important infrastructure projects abroad”.

Brad Parks, executive director at AidData, says that India’s ExIm Bank credit generally carries more concessional terms than Chinese loans. Unlike China’s ExIm Bank, India also selects contractors through a competitive bidding process, provided the proceeds purchase Indian goods and services. The government says these schemes create “jobs, demand for material and machinery in India and also a lot of goodwill”, according to a 2018 press release.

But while state-owned firms previously took the lead on such contracts, analysts say no prime minister has gone as far as Modi in promoting the private sector in their place, cultivating deep-pocketed, fast-moving Indian tycoons to execute his development agenda at home and abroad.

Sajjan Jindal, the chair of steel-to-energy conglomerate JSW Group, told the Financial Times earlier this year that Modi was “close to every business house in India which is growth oriented, which is nationalistic, which is willing to take big bets”.

These include Indian companies like Tata, Larsen & Toubro and the GMR Group, who have all built up significant business abroad. But chief among them is the Adani Group, which has built the country’s largest private logistics network across ports and airports. Adani, who has a years-long relationship with Modi, has quickly become one of the most prominent Indian players in the region.

The Adani Group in November began work on a new $700mn terminal at Sri Lanka’s Colombo port, a deal agreed after Sri Lanka authorities last year cancelled a pre-existing Indian project.

It also won contracts for two energy projects on the island, jointly bought a concession for Israel’s second-largest port, announced its intention to invest in Tanzania and will next month start supplying electricity from India to neighbouring Bangladesh.

Adani says his overseas investments are sound business decisions which also help India and the region’s interests. “We don’t do the role of a country,” Adani told the FT in a recent interview. But “we are an Indian company, and wherever our country’s interest is there, we always feel there is nothing wrong to help India, to help neighbours”.

In “our area of interest and expertise — like port development, electricity generation, green hydrogen, logistics — all these areas we try our hand”.

Xavier says that, given the higher risks of operating in certain south Asian countries, large private companies “informally seek support from the government of India for political and sovereign guarantees.”

The public-private partnership is vital, he adds. “Any infrastructure investment requires Delhi’s diplomatic weight to be successful.”

But the proximity between Modi and leading Indian capitalists has proved controversial.

Critics both at home and overseas accuse Indian authorities of helping Adani, for example, win lucrative contracts. Sri Lanka’s electricity board chair MMC Ferdinando told the country’s parliament in June that a renewable energy project was given to Adani “under pressure from Modi”, something all parties strongly denied.

Others argue the significant Indian sourcing requirements tied to loans crowd out opportunities for domestic firms. “It is like an open playing field for Indian companies,” says Hasan Mehedi, a climate and energy activist in Bangladesh.

Analysts say the problems stem in part from the lack of regulation and transparency around how private companies lobby and liaise with Indian authorities overseas.

But this remains a project in its infancy. Even as critics in India and elsewhere point to the shortcomings of China’s BRI, they say it will take years for India to prove it can scale up its ambitions to those of its larger neighbour.

“Going abroad has its own sets of challenges,” said Srinath Raghavan, a historian at Ashoka University. “Politics can take its own turn.”