The port sector has relatively few health and safety standards, with no minimum baseline for critical risk activities

New Zealand’s port sector has one of the largest divides between good and bad operators and most inconsistent practices of any industry, according to a cross-industry report.

Yesterday, The Port Health and Safety Leadership Group, made up of industry, unions and Crown entities, released a multi-year action plan in response to the series of high-profile fatalities in the past few years.

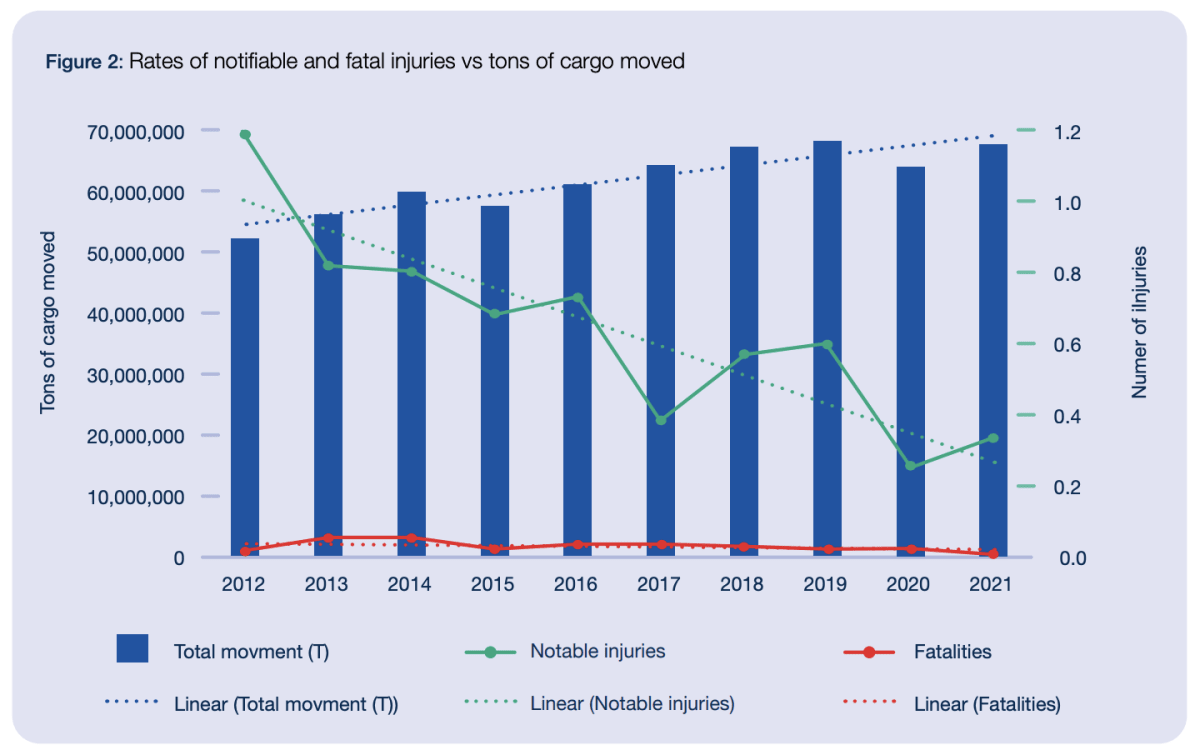

New Zealand has had 18 deaths and 397 reported injuries in its ports over the past decade.

READ MORE: * Ports of Auckland fighting to secure its future * Don’t expect cheap freight anytime soon * Shipping congestion will ease once recession hits

International comparisons are difficult given differences in cargo and mechanisation.

In the United States ports workforce, ports workers deaths at up to 15.9 deaths per 100,000 workers, up to five times the rate of the country’s total workforce overall.

For New Zealand, stevedore fatalities occur at a rate of approximately 20.2 per 100,000 port workers, the second highest rate of all industries.

By quantity of product moved, there is less than one fatality per 20 million tons of cargo moved through New Zealand ports. This is two or three times more common than comparable nations Hong Kong or the United Kingdom.

New Zealand’s fatalities are in line with Australia’s, but Australia carries significantly more cargo.

Inconsistencies

The report said Ask Your Team, the employee experience provider contracted to survey workers, found the divide between lowest and highest scoring companies in some survey questions were among the largest of any sector they had seen.

Inconsistencies were across training, information sharing, worker engagement, traffic management, fatigue management, maintenance and incident reporting.

The report said though each of New Zealand’s ports had unique features to take into account when designing operational practices and procedures, in some cases there was no clear rationale for the large differences in risk mitigation controls.

It said those differences could lead to poor safety outcomes.

Compared with other high-risk industries such as forestry and construction, the port sector has relatively few health and safety standards, with no minimum baseline for critical risk activities.

Maritime NZ is now looking into developing such standards or a code of practice, which many other countries already have.

“There has been marked success in other sectors in New Zealand such as forestry, construction and agriculture, and in ports overseas, in achieving positive health and safety outcomes through the introduction of standards to create a baseline which industry can work off,” the report said.

A comprehensive document for fatigue management already exists, but container stacking, data and reporting, and training have been identified as future candidates.

No stevedoring plan

Stevedoring was identified as the area needing consistent baseline standards – one of if not the most dangerous activities on a port where a significant number of injuries and fatalities take place.

Examples of inconsistencies include a lack of standard operating procedures from one stevedoring company to another, sometimes with two parties working at the same time but differently.

“For example, some stevedores will back a forklift with a full pallet on the forks to ensure better vision, while others will drive the same load forwards, despite the reduced visibility.

“While there may be good reasons for differences in SOPs [Safe Operational Plan], in some cases there is not.”

The approved code of practice Maritime NZ plans to take the lead on developing wouldn’t impose new requirements but clarify what is reasonably practicable and expected for all parties.

It would likely be based on the Australian framework. According to the Maritime Union of Australia, there have been zero fatalities in its organised stevedoring activities since their framework was introduced.

The framework will be a priority, with an intention to complete the plan in June and deliver for ministerial approval by September.

Other key issues were the implementation of a consistent fatigue management system, simplifying reporting and jurisdiction on ports, improving incident reporting and taking action to resolve workforce shortage problems.