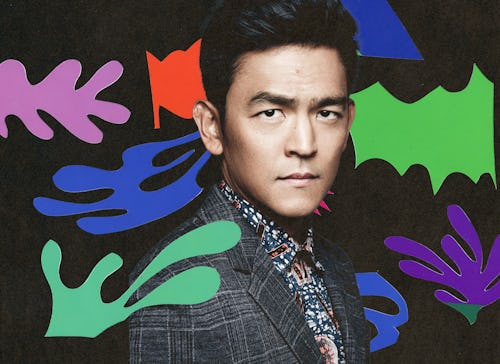

John Cho wasn’t supposed to write this book. And on paper, it might not seem particularly advisable: In the wake of the protests following George Floyd’s murder, an actor decides to write a debut middle-grade novel revisiting the 1992 Los Angeles uprising that exacerbated the already tense conflict between Korean Americans and Black Americans in the city. Cho, who’s best known for his roles in Harold & Kumar, Star Trek, and the recent Cowboy Bebop, forgives any uneasiness readers may feel — he felt it himself when he pivoted away from his original idea of a fun young adult mystery novel. Instead, he wrote Troublemaker, which follows 12-year-old Korean American Jordan as he ventures into the L.A. streets to try to deliver a gun to his father and protect their liquor store on the first night of the riots.

“I wasn't confident … this was gonna work out,” Cho told me over Zoom. But his novel is a delicate introduction for young readers to a nexus of thorny subjects: police brutality, gun violence, and the weight and potential myth of the American Dream. It attempts to unpack the ’92 riots that, 30 years later, many still struggle to understand and wrestles with the messy context that led to the clash between the Korean and Black communities and widespread destruction of L.A.’s Koreatown: namely, the acquittal of four police officers who brutally assaulted Black man Rodney King, as well as the murder of 15-year-old Black girl Latasha Harlins by a Korean store owner, whose jail time-free sentence was upheld in a judge ruling one week before the riots.

Cho felt compelled to write about this complex lineage of historical injustice and racial conflict in 2020, amid rising anti-Asian violence — which the actor discussed in a Los Angeles Times op-ed — and the national Black Lives Matter movement. Cho spoke to Mic about how his own view of the riots has changed over time, why he feels uncomfortable with the term “race relations,” and how he sees the current political moment for Asian Americans.

What prompted you to change course and write a book like this?

John Cho: I was thinking about the line of life, from my parents to my life, to my children's life, and our time in this country. When we came to America when I was six years old, I had a certain vision of what the country was gonna be, and there were things that I took for granted — that things would improve generation to generation. In some ways, that has proven to be true. And in other ways, in 2020, it looked like [it wasn’t] true. Having to discuss with my children whether their grandparents were safe on their walks and explain why people might hate Asian Americans was very difficult. That was a conversation my parents might have had with me, but [I didn’t think] I would have to have [it] with my children — that really knocked me on my heels.

You don’t actually bring the reader into the riots themselves. What was your ultimate goal with this story?

I really wanted to focus on the family and a story of love between the members of this family. That was the thing I wanted to push the most. And the circumstances were a way to put pressure on this family.

Where we started was probably the most remembered image of Koreans from the riots: the men on the rooftops with their rifles. I thought, we have to go into that person's home and understand that person. So I purposefully avoid any scenes of the riots. Jordan has been whipped into a paranoid frenzy by the news reports and the deluge of images in the media — today, I guess it would be [akin to] Twitter anxiety. He’s seeing all these things, and I wanted [him] to have one-on-one experiences and have conversations with people face-to-face.

What is your personal relationship to the riots? Were you in Los Angeles at the time?

Thankfully, I didn't know anyone whose families were affected directly. I was in the Bay Area for college. I was watching it on TV, and it was a lot of anxiety about [the Korean store owners’] safety. I was thinking, they need to get inside and they need to get off those rooftops. Now, I kind of understand that impulse better [and] what those businesses meant. That was their entire future. That was college, that was food on the table. It was their dream. It was insurance. It was an heirloom to be passed on. But at the time, I was very panicked, and I thought perhaps there was gonna be mass death.

Then and now, we’ve heard a lot of rhetoric about how protesting is fine, but looting, rioting, or any form of resistance is unacceptable. In the book, Jordan asks Mr. Gary, a Black man he encounters, a question he previously heard his mother ask: “How is this helping?” Was that reflective of your own thinking during the 1992 riots?

[In 1992], I saw the whole thing as rudderless and thought, nothing good can come of this. I understood why people were in the streets, but I also saw it as dangerous. Primarily, I thought, what good can come of people being hurt and property being destroyed? Now, I understand the impulse so much better. I didn't really understand the historical context of why those people were in the streets, primarily because it wasn't told to me.

That's another thing I was thinking about in the summer of 2020. For people who don't recall the Rodney King beating, it was extraordinary because it was something that had been happening in the darkness and a motorist happened to catch it on his Handycam. And so you were like, “Well, there it is, there's the evidence. Case closed.” And yet the men went free. And in the ensuing years, laws were passed, police had to wear body cams, and then people had cameras in their pockets. And you thought, well, that ought to solve that — to no avail. Over and over, these incidents of police brutality continued even while [the cops were] looking at a camera that was filming them. Even Derek Chauvin seemed to be looking down the barrel of the lens while his knee was on George Floyd's neck. That was another thing that was so dismaying, because I thought that this technology would change everything. And it did not.

Mr. Gary gives Jordan a delicate and nuanced response that seems to reflect this fury that Jordan could never understand. Was the intent here meant to teach readers something you didn’t know at the time?

What would a man of that age realistically say to a boy of that age, in that circumstance, on that day? I thought it would be justified for him to give some context to the kid. He's a kid, and no matter what differences there were, I thought it possible that an adult [would] help a child understand what was happening.

That conversation happens organically, but also randomly. Both characters could be seen as stand-ins for the Korean community and the Black community, trying to address a wound. Did you think about this scene as a way of addressing the sensitive historical tension?

I am not a politician, I’m no historian, and it wasn't my intent to necessarily patch up any relations. In fact, sometimes I cringe at the phrase “race relations,” which is used in the media a lot. I often think it's not a relationship issue — the relationships will follow after the issues of justice are addressed. So I didn't think of it as offering to address a broken relationship, but an examination. It was a matter-of-fact issue that I thought needed to be in the book if I was to place a story on that day.

There are a lot of issues that contribute to the fracturing of relations [between the Korean and Black communities]. Some of it was timing. The murder of Latasha Harlins preceded [the riots], so that informed some of that animosity. And some of it was situational. The police left. We were neighbors and they left both neighborhoods [Koreatown and South Central] and went to the federal building in Westwood. So there was no mediator, and we were in the crossfire. And some of it was historical in the sense that the Koreans' view of African Americans were probably informed by [American movies and TV that depicted] African Americans [as] thieves, troublemakers. And then [there’s] what happens when you have economically disadvantaged groups living amongst one another. There was a lot brewing there.

You mentioned how you’ve come to understand what was at stake for those Korean store owners on the roofs with rifles. Yet toward the end of the book, Jordan’s store owner dad says he chose not to bring a gun because he had an experience in the war that led him to see [a gun] not as something that protects, but that kills. Was his reasoning a callback to those real-life store owners, a kind of plea for them to make a different decision?

That was pretty much a quote from my father. He had a very similar experience to the one that Jordan's father recounts back in Korea. It may have actually been the riots that led to my dad excavating this memory for me and saying, “I would never own a gun anymore. I would never handle that.” It was definitely a callback to those images of the Koreans on the rooftops with the guns. And I was also thinking about the gun in America. [It’s] a proxy for so many things: prosperity, independence, power. And to an immigrant, those [things] are colored by looking at America from afar. So it's a stand-in for a lot of what America represents. And for Jordan, it's adulthood, selfhood, and subjectivity. But at the end of the day, [it’s] actually a thing designed to kill people. To some extent, it can be used responsibly, but very often it's used irresponsibly.

In the book, Jordan talks about his encounters with law enforcement, and his dad says that he didn't think that they could rely on police if they were in danger. Is that reflective of your family’s relationship with police?

There's an incident in the book that was taken from our life. In the book, it’s a robbery; but in our lives, somebody shot at our front sliding door with a BB gun, and it shattered. We called the cops, and I very vividly recall it being very futile. I think I called the cops actually, because my parents were like, that's not gonna do anything. In the book, Jordan's memory is of them not taking off their boots as they come in and stain the carpet. That was something that happened to us.

Later, I went to Korea and met my uncle who was a cop. He was very curious about what happened in L.A., partially because he was interested in Americans’ attitude toward cops. That's when I learned that Koreans kind of looked down on cops because they were known to take bribes back in the day. There was an assumption that you had to fend for yourself, which makes sense for any immigrant community — not relying on anyone, not assuming the government is gonna help you. So that was built into [the book], too. And of course, the police leaving Koreatown [during the riots] confirmed those suspicions.

Jordan’s dad tells his son that he brought his family to America for a better life, but now realizes things might be worse here. Have you experienced or witnessed a similar shattering of the idea of America, for your parents or for yourself as a parent?

I'm certainly worried about where my country — and I mean the United States — is heading. I've always assumed that we were an imperfect country that was going toward perfection, that we were trying to perfect ourselves year by year. It hasn't felt that way lately, so I'm worried, and I hope we can course-correct. When you have children, you are reliving your own childhood and also living your parents' adulthood at the same time and placing yourself in both bodies. I had an extension of that experience as it relates to immigration, because I spent the last two years in New Zealand for work and brought my family with me. That was a wonderful time, but it was also a complicated time living in another country. It made me very naturally think about what that experience was for my parents. I don't have a clear answer for you, except that I had been thinking about those things, and those three generations represented in the book — the grandfather, the father, and the children — to consider them as one existence and what that line looks like.

In 2020, you wrote an op-ed about how the model minority myth could seduce and silence our parents, and in turn their children. There’s been a lot of recent discourse about the incoherence of Asian American political engagement. In light of the ongoing rise in anti-Asian violence, do you feel this is a turning point for Asian Americans in thinking of themselves as a community?

In some ways it's an unnatural collective, as we come from very disparate cultural backgrounds. However, if it's a conscious decision to lock arms — and in some ways, it's a response: we're seen as one, so let's act as a unified political force — I think we can use that identity to our advantage for political and cultural gain. If we do it consciously, I think there's a moment here worth taking.

It seems that there is always this caveat of how “unnatural” the collective is, as you put it. Do you see that solidarity becoming something that feels organic and less fraught?

Sure. I think it can be all of those things at once. It can feel organic. It can feel political. It can feel of the moment, and it can feel permanent. And that's okay. As I said, we come from such disparate backgrounds — it’s never gonna feel ideal. I don't think we'll ever get to a place where it feels completely natural. But whatever form it takes, I'm very open to what it is and just accepting it on its own terms.

What do you hope readers get out of this book?

I hope that kids just like it as a story. I was very conscious of [writing] a book that I would've read when I was a kid. I really liked stories about kids being away from adults and what they do without supervision. So I hope they just enjoy it on a visceral level that way. Maybe then it’s an opportunity for parents to answer questions about some of the things that have been going on. And I really just wanted to see an Asian American boy on the cover of a [young adult] book. I know I would've been delighted to walk into the library and see that kid looking back at me.