“My family is spectacularly bad at endings,” admits Noah Turner, the narrator of Shaun Hamill’s A Cosmology of Monsters. “We never handle them with grace. But we’re not great with beginnings, either.”

This, it turns out, is a bit of an understatement. The Turner family, bless their haunted hearts, aren’t all that great at a lot of things—their existence in Vandergriff, Texas, a fictional small town near the Metroplex, is marked with financial instability, resentment, and a propensity to hurt one another at nearly every opportunity. Lovable they’re not, but they’re great at scaring people—as is Arlington native Hamill, whose debut novel is a beautifully crafted and terrifying thrill ride of a book.

The novel begins with Noah recounting his parents’ courtship in Arkansas, where his mother, Margaret, is a student at a conservative Christian college and takes a job at a bookstore to make ends meet. It’s there she meets Harry, a horror aficionado with a soft spot for the works of H.P. Lovecraft. (Harry, Noah explains, “had a taste for the macabre, and an extraordinary patience for dry, overwrought prose.”)

The two marry, move to North Texas, and start a family, with Harry working in Fort Worth at a mind-numbing state job that he barely tolerates. Bored with his existence and still obsessed with all things ghoulish, Harry decides to erect a haunted house in his family’s yard, despite his wife’s misgivings. The neighborhood attraction is a hit, but Harry doesn’t have long to enjoy it. Shortly after it opens, he dies of cancer, leaving his family destitute.

Margaret uses the proceeds from Harry’s estate—a collection of rare horror novels and comic books—to open a comic book store. The business barely keeps her family afloat, and in the little free time she has, she does her best to take care of young Noah and his two older sisters: shy and sensitive Eunice and rebellious Sydney, a high schooler and aspiring actress who’s a drama queen in both senses of the term.

But when the family car gives out, Margaret is forced to try to make money with a side business that she’d hoped to forget: her late husband’s haunted house, which she reopens in a warehouse and christens the Wandering Dark. The venture proves to be a success, but not long after it opens, Sydney disappears, introducing even more trauma into a family that’s already had more than its share.

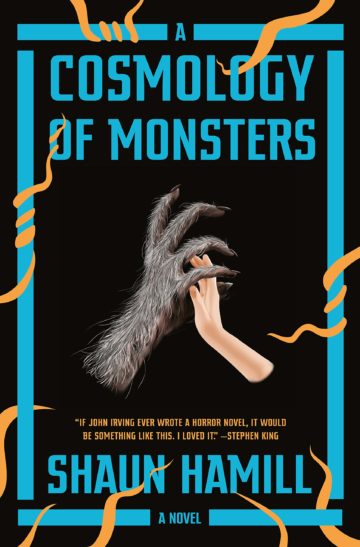

Noah, meanwhile, has made a secret friend: a monster with “tufts of brown hair, orange eyes, and protruding snout,” who visits the lonely boy at night, always begging to be let in the apartment. The friendship abides throughout the years, even when Noah becomes a teenager with a job at the Wandering Dark, wearing a monster costume to scare unsuspecting visitors. (“I was a good monster,” Noah says, with eerie foreboding. “I loved the work.”)

As time progresses, the reader learns that Noah isn’t the only one to have encountered a mysterious creature, and that his family history is even darker than he suspected. Family secrets have a way of coming out, and Noah and his family’s lives are upended at the book’s terrifying conclusion.

A Cosmology of Monsters covers four decades in the Turners’ lives, from the 1980s to the near-present day. Hamill uses the jumps in time wisely; the cuts between years are never jarring. And he avoids the nostalgia trap that tends to mire other writers who choose the recent past as their settings.

He does make some sly references, though, which he then subverts in seriously creepy ways. Noah’s relationship with his monster friend at first recalls E.T., until Hamill has the monster offer to help the teenage boy masturbate, in a scene that’s somehow even more unsettling than it sounds. (This is something of a setup for a sex scene later in the book, involving a young woman with physical features not unlike Noah’s sisters. Hamill traffics in the disturbing, like Stephen King at his most upsetting.)

But A Cosmology of Monsters is almost more John Irving than King, since Hamill writes about family, sex, and all things grotesque with a gleeful openness. In a way, the novel is a twisted coming-of-age tale, with all the benchmarks of male adolescence—shame, jealousy, anger, and id—personified in the form of a monster and transformed into literal horror.

It’s a novel that’s both beautiful and terrifying, which isn’t the easiest thing to pull off. Hamill knows how to craft great horror fiction, but he’s also a keen observer of how families cope with loss and with one another. He recognizes that not everything gets resolved neatly, that sometimes darkness just leads to more darkness. “Life makes monsters of everyone,” Harry muses at one point, “but it’s always possible to come back.” Yes, Hamill seems to respond, isn’t it pretty to think so?

Read more from the Observer:

-

More Highways, More Problems: Highway expansion is the Lone Star State’s status-quo solution to easing traffic—but it actually leads to more congestion and displaced communities.

-

Molly Ivins on Climate Change Deniers: “One theory of government is that it only reacts to a crisis; trouble comes when we cannot even agree on what a crisis is,” Ivins wrote in a 1995 column about Congress’ lukewarm response to the threat of global warming.

-

The Butterfly Effect: As monarch populations continue to decline, a grassroots movement of native milkweed stewards is emerging across Texas.