My experience with Samara Hersch's online version of Body Of Knowledge (At Home), which was part of Germany's Impulse Theater Festival last year, has since got me interested in the question of what it is we do in theatre as audience. In Body Of Knowledge, the audience engaged in conversations with teenagers via WhatsApp, they in their own home, we in ours. The performance made me more attuned to the act of listening -- something we do in theatre without thinking or being asked to.

When theatres all over the world began shuttering two years ago due to the pandemic, the meaning of theatre was widely discussed by professionals and enthusiasts. I remember American director Anne Bogart at an online talk at the Singapore International Festival of Arts quoting or paraphrasing legendary choreographer Martha Graham's: "Theatre is a verb before it is a noun, an act before it is a place."

It was as if we were returning to the theatre in our mind by returning to the roots of it, or at least making our way there. In my review of Body Of Knowledge, I wrote that the piece made us return to the root of the word audience, which means to hear or to listen, even though we were not in the theatre together.

This year, for the first time, I attended part of Impulse Theater Festival in person as part of the North Rhine-Westphalian Office of Culture's International Visitors Programme. Seven arts and culture professionals from six countries were invited to attend the festival between June 14 and 19.

The festival itself ran from June 9-19 and took place in four cities in the North Rhine-Westphalia state -- Mulheim an der Ruhr, Dusseldorf, Cologne and Essen. There are three parts of the festival: Showcase (independent theatre productions and video installations); Impulse Academy (workshops, panels discussions, lectures); and City Project (site-specific projects that engage with local issues).

Impulse Theater Festival is the second festival that I've physically attended since travel restrictions began to ease earlier this year. Germany no longer requires people to present a vaccine certificate upon entry into the country or any place within it. We're allowed to go mask-free indoors, except on public transport. We can watch performances, discuss shows over food and drinks and dance together without social distancing.

Now that we're back together again, what do we do as audience once we are present in theatre and in the presence of others?

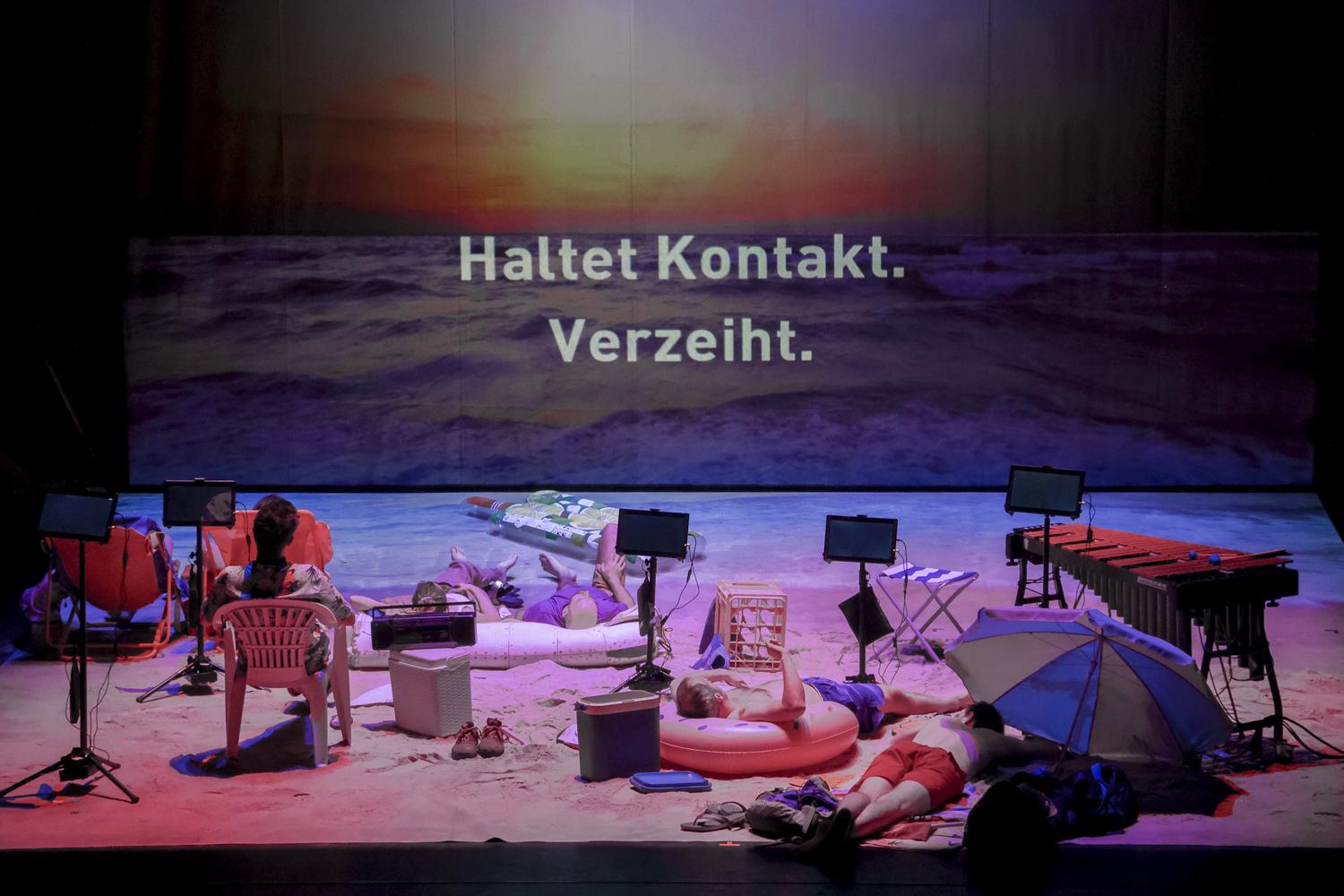

This time, the performance that had me chew on the question the most was Berlin-based company Rimini Protokoll's heartbreaking and challenging All Right. Good Night: A Play About Disappearance And Loss. Directed and written by Helgard Haug, the play tells two stories in alternative chapters, one of Haug's father's struggle with dementia, another of the Malaysian Airlines Flight MH 370 that disappeared in 2014. The performers present in the theatre were musicians from Zafraan Ensemble, playing music composed by Barbara Morgenstern and wordlessly enacting scenes. The stories themselves played out in words projected onto the screen in German and English. So for two-and-a-half hours, we all sat there and read the play, silently to ourselves.

I was incredibly moved by the text. The live music never distracted me from the act of reading. It was part of the reading. Free from sentimentality, the music never tried to shape or define the emotions of the text. It was there more as a uniting element and reminder of the liveness of the experience.

Still for days, the play puzzled me. What does the act of reading mean in the live performance context? Reading is one of my favourite activities, something I find such deep pleasure in. But reading collectively, silently, in theatre? What was the artist's purpose of mounting a show, bringing a bunch of people together in one space, just to have us read the stories?

I suppose in the act of reading, we're always listening, just as when we are sitting in the theatre as audience. When we read, we create and listen to a voice or many voices of our imagination.

In this production, we were reader and audience. Except that when we read a text, our imagination is freer than when we watch a story being enacted in front of us by performers. Suddenly the people populating these stories acquire hundreds, perhaps thousands, of voices and images as they are being read about by the people present in the same space all at the same time. It was a private act, done communally, in a public space.

The act of reading here not only underlined our presence in the theatre, it also underlined the physical absence of the real people in the stories -- Haug's father and all the 239 passengers and crew members on board Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370 and their loved ones.

But theatre doesn't have to be participatory or highly conceptual for the audience to feel that their connection to the artist onstage is sharpened or heightened. Vienna-based choreographer, performer and theoretician Michael Turinsky's Precarious Moves is a solo in which he merely moves and performs various tasks onstage while speaking directly to the audience. The artist's work focuses on disability, and he himself has cerebral palsy.

Due to his condition, Turinsky's speech can be difficult to understand. He performs in English, but the show comes with both English and German surtitles. Precarious Moves was one of the best communication and interactions in theatre I've ever experienced. Nobody was doing anything unconventional. He performed onstage. We sat in our seats and watched and listened. We were never asked to do anything, except once when the artist asked for a volunteer from the audience to fold a paper boat.

Turinsky spoke of the evolution of the piece and pondered questions of movement -- our movements and his movements and how we can move together with little adaptation on both sides -- and questions of choreography -- of movements that are organised and ones that are organically formed. He performed simple activities as he spoke -- opening a bottle, drinking from a straw, moving around in his wheelchair, getting out of his wheelchair, driving a toy car, walking and standing on his knees, pouring water into a basin, assembling a toy race track, putting himself back in the wheelchair.

When Turinsky performed these activities, including speaking, they felt significant because he cannot move or speak the way most of us can. In a way, he cannot do them without a certain amount of "organisation" or choreography. The audience was not there to merely watch the mundane in theatre. We were there to ponder the mundane of a person differently abled from many of us.

Even though his daily life and movement have to be more choreographed, nothing in the show seemed performative. Everything felt genuine. It was perhaps because when Turinsky spoke, he really spoke to us. With his natural warmth, humour and charisma, he made our presence feel acknowledged at all times. The audience was not there just to listen to what the artist had to say. We were invited, in the gentlest possible way, to ponder the questions that he posed, through words and actions, along with him.

And since both his actions and words were spare, his approach so gentle, there was ample room for complex questions about disability and coexistence. With his gentleness, Turinsky turned the theatre into a wide-open space for collective contemplation.

For more information, visit impulsefestival.de.