MP and former cabinet minister, David Davis stood up in the House of Commons recently and told Prime Minister Boris Johnson to resign.

You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. In the name of God, go.

His words had resonance – they had been heard before in the Commons.

Mr Johnson implied that he was not familiar with them. This is particularly surprising as Mr Johnson has published a book on Winston Churchill. On May 7 1940, following the invasion of Norway by Nazi Germany, former First Lord of the Admiralty, MP and ally of Churchill Sir Leopold Amery stood up to address the prime minister with similar words to those David Davis did 82 years later.

The then prime minister was Neville Chamberlain. He had held the position since 1937, about as long as Boris Johnson had held the office by January 2022. Both Amery and Chamberlain had experience of politics in Birmingham and thus had something in common, which added bite to what Amery said.

Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go.

Within days Chamberlain was gone and Winston Churchill became prime minister.

Both men knew in 1940 that Amery was paraphrasing Oliver Cromwell.

To all of Parliament

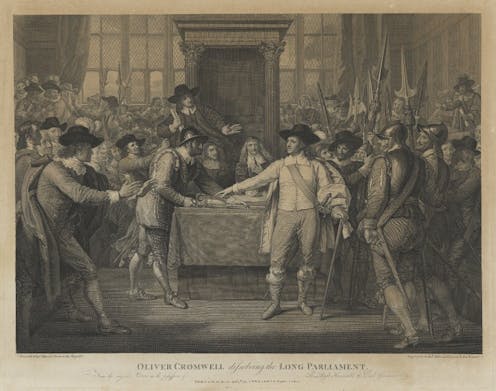

On April 20 1653, Cromwell addressed parliament:

It is not fit that you should sit here any longer. You have sat here too long for any good you have been doing lately … In the name of God go.“

While like Davis, Cromwell was turning on some former allies, the circumstances were very different. For a start, Cromwell was speaking to all the MPs in the house at the time.

The civil war started as a rejection of Charles I’s attempt to enforce Anglicanism across Scotland, which led to a number of battles that resulted in Scotland seizing the whole of Northumberland and Durham. Needing money to restart the war, Charles went to parliament, which didn’t agree with renewing the conflict. War broke out between royalists loyal to Charles and parliamentarians over how the "three kingdoms” of England, Scotland and Ireland should be governed.

Between 1642 and 1646, an increasingly bitter war was fought in England and Wales, which was won by parliament. This short war was followed by fractious negotiations which moved further and further away from a settlement. In 1648, King Charles’s supporters in England and Wales launched another attempt to support the king who was by this time a prisoner on the Isle of Wight.

War again raged across the British Isles, the Scots joining with the king and an alliance of royalist and Irish forces in Ireland renewing the conflict there. The war in Britain was brief and resulted again in parliament triumphing. The king was brought to trial charged with treason for renewing the war. He was found guilty and executed.

At the beginning of 1649, the House of Commons declared itself the only true representative of the people and abolished the House of Lords. The monarchy too was dispensed with and the Commons, along with a council of state, became the government of what it declared to be a republic consisting of England, Wales and Ireland.

In 1650, after a successful but contentious campaign in Ireland, Cromwell was appointed commander-in-chief of the armed forces and launched a campaign against Scotland, which had declared the late king’s son to be his successor as King Charles II.

After Cromwell’s military victories at the Battles of Dunbar and Worcester over the Scots and their royalist allies, he had urged parliament to introduce radical changes to the way government and the law related to the people of the new republic. He envisaged a fairer society and new beginning.

They must go

By 1653 this optimism had faded. Parliament had not introduced the great changes in law or government that Cromwell had hoped for. It had angered the army which had brought it victory, and only Cromwell, as commander-in-chief, could keep the military from taking action over the winter of 1652-3. What was uppermost in many politicians’ and soldiers’ minds was the need for a general election.

The parliament which sat in April 1653 had been elected 12 and half years earlier in October-November 1640. Inspired by the radical political movement the Levellers, which had in 1647 proposed a new constitution for England and Wales including a broader electorate, parliament had set about reshaping constituencies. While this was a radical change, with many growing towns were given MPs for the first time, the movement towards actually calling an election was painfully slow.

Cromwell and his political allies thought that before the fated speech on April 20 they had convinced their MP colleagues to speed things up. While Cromwell was holding a meeting at his London home to plan an interim council to govern during the election period, news was brought that parliament was discussing a plan that would do little to prevent royalists from being elected in sufficient numbers to overturn the republic.

Cromwell gathered a group of soldiers and went to take his seat in parliament – he had been an MP since 1640. At the point at which the election bill was to be put to a vote, Cromwell stood up and told parliament to go. The soldiers, who he had left outside the chamber, were called in and the MPs were forcibly expelled. Within days a new assembly was called to sit in the Commons and create the new republic Cromwell had in mind.

Just five months later, what was known as the Little Parliament because of its small number of members dissolved itself and handed power to Cromwell. In December 1653, the new constitution established the protectorate, a nation ruled by a lord protector rather than a monarch.

By citing Amery, who was, in turn, quoting Cromwell, Davis distanced himself from the controversial general who was, in effect, throwing out a whole parliament rather than attacking a single former political ally.

Nevertheless, the words are powerful ones. They indicate that a person or body has failed and that it is time for him or them to step aside. These words are game-changers. A parliament and a prime minister were displaced by their utterance, but it remains to be seen what their third very public use will result in.

I have in the past received research funding from the British Academy and the AHRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.