Ecotourism is practised across national parks in the country, as well as Nature reserves across the Nilgiris and Western Ghats. While most tourists are curious to spot tigers and lions, over 14,000 leopards roam the country now, with dedicated spaces devoted to their conservation, offering a chance for wildlife enthusiasts to watch them in their natural habitat. As International Leopard Day is observed on May 3, we take a look at how these majestic cats comfortably cohabit urban and jungle milieu around humans.

At Kabini, in the Nagarhole Tiger Reserve in Karnataka, Mithun Hunugund, a wildlife photographer, conducts eco-tours through the wild. “My father worked with the Forest Department, and so I’ve grown up in these forests, now spending close to 20 days every month in the wild,” he explains. Having tracked leopards in the reserve, as a photographer first, he worked on a documentary, The Real Black Panther, for National Geographic Wild, documenting Saya, a melanistic leopard that wears a rich black coat and roams through Kabini. Since 2017, Mithun has taken visitors at The Bison Resort in Kabini, on eco-safaris. All guides have to first receive training with the local forest officials as naturalists. “It’s important to note that every visitor comes in with a set of expectations. Once we enter the reserve we explain the dos and don’ts for the duration of the tour, and then dwell on the flora, fauna and the importance of heighting your senses to be fully present during the safari.”

At the country’s first Leopard Reserve, Jhalana Leopard Safari Park in Malaviya Nagar Industrial Area, Jaipur, Rajasthan, tourists are treated to leopard sightings of over 35 big cats, with close to seven leopards living within the tourist perimeter. Visitors are made aware of the conservation efforts to keep the leopards safe. Kuldeep Singh, a tour operator at the reserve explains, “Our Gypsy vehicles are retrofitted to camouflage in the jungle along with a strong frame that protects both the tourists and the fauna. We insist on clothing that blends in with the hues of the jungle and strictly prohibit flash photography.” Drivers on the safari are trained by the local Forest Department to track alarm calls of the animals, sport pug marks, and keep a safe distance. On May 22, 2022, to mark the International day for Biological Biodiversity, the second leopard reserve in Amagarh, Rajasthan was open to the public, with 16 leopards and 250 different cat species, spread over 524 hectares.

As per official records of the reserve, over the past three seasons, Jaipur’s leopard population has experienced a significant increase with 35 leopard cubs born between January 2019 and August 2021.

While eco-safaris bring tourists to leopards, following norms and a deep respect for their spaces, leopards have been coming to people in urban spaces, for decades in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park and Aarey Milk Colony in Maharashtra. Wildlife photographer Nayan Khanolkar, has documented leopards in urban spaces since 2013, when he laid camera traps in Aarey on the outskirts of Mumbai, and caught his first glimpse of Luna, “I still remember it was in 2014 at the end of the monsoon, that this young leopard first walked by our camera trap. Leopards require a vantage point to monitor their territory which is typically feline behaviour, and so they will come to altitudes now occupied by human settlements, for this purpose. The Warli tribes who have lived in these areas have co-existed alongside the leopards for decades now.”

While Luna, the young leopard walked by the camera traps in Aarey, “she never shied away and we could tell she was very comfortable around humans, and this way we could track her through people’s backyards and through Sector 15 to the other end of the Aarey area,” adds Khanolkar, who last photographed Luna in 2018, but knows of her eight cubs through the years, as well as nine other leopards who came to urban spaces, though , “not as comfortably,” says the photographer, who has since documented Rusty Spotted Cats, for research. He speaks of awareness programmes conducted by the local forest officials to sensitise the public to this co-existence, because , “animals use standard patterns for their movement and if we build anything in their way, they will learn to manoeuvre around it.”

Eco tourism in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park has benefitted from a more curated reporting on the matter as well. Dipti Humraskar, a wildlife biologist and Nature educator from Wildlife Conservation Society, India ( WCS) has been a part of the Mumbaikars for SGNP (Sanjay Gandhi National Park) since 2011, the citizen-science initiative of the Maharashtra Forest Department that was formed to address the human-leopard interactions around the park and she manages interactions with residents, training and capacity building of media, Police department and Forest department through this project. “Sunil Limaye, director at the park at the time, wanted to include all stakeholders in the process, so residents, media, and the Forest department worked in tandem. We had to change the narrative from sensational to sensitive reporting on the subject as well,” she explains.

Khanolkar opines it is imperative to generate employment and involve local communities in the area, in any eco-tourism initiative. “Training them as naturalists, and guides so they can follow certain rules when there are sightings, and make movement easy for the animals, while allowing safe sighting as well.”

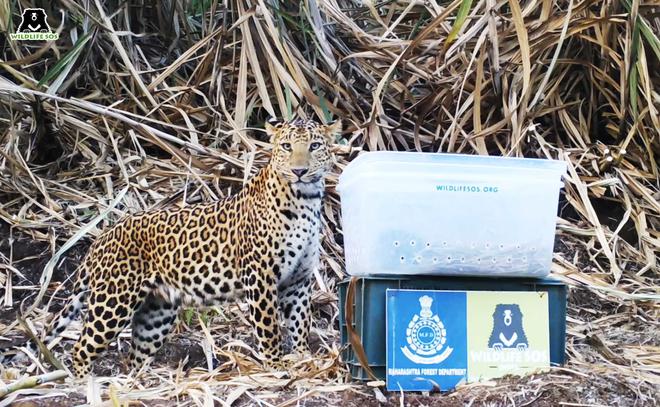

In the sugarcane belt in Maharashtra, leopards have interacted with humans often, with cubs stranded in the thick, tall fields, have their reunions facilitated by Wildlife SOS, an organisation that undertakes wildlife conservation, rehabilitation and awareness programs. “Between January 2020 and January 2022, we reunited 24 cubs with their mothers. To date, Wildlife SOS and the Maharashtra Forest Department have successfully rescued and reunited over 80 leopard cubs,” explains Kartick Satyanarayan, co-founder at Wildlife SOS, adding, “a growing population, expanding farmland and depleting forests have pushed the margins of human habitations closer to the existing forest areas.” During the pre-harvest and harvest season, farmers often come across stranded cubs in the fields which can lead to conflict situations. ”If female leopards are unable to locate their cubs, it is natural for them to turn defensive or aggressive and they pose an immediate threat to humans in close proximity”

For the reunions, Wildlife SOS in cohesion with the Forest Department, work at dusk or at night on the same day, to minimise the disturbance from human activities. A Wildlife SOS veterinarian conducts an examination of the cubs to check for injuries, ticks and infections. “Once they are examined, each cub is implanted with a microchip consisting of a unique identification number, fitted near the tail region. As per the guidelines issued by the Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change (MoEFCC), animals that are in captivity or are being released back into the wild have to be microchipped, as it helps monitor their range and movement patterns,” he adds, “We’ve found that minimising the time of separation between the cubs and mothers appears to be an important contributing factor for a successful reunion.”

For those leopards that cannot be reunited in the wild, Wildlife SOS in collaboration with the Maharashtra Forest Department established the Manikdoh Leopard Rescue Centre in Junnar in 2007, and the centre is home to over 35 leopards and provides temporary or life-time care, for leopards injured by villagers or trapped in conflict situations. The centre also houses several orphaned leopards who cannot be released back into the wild. Kartick concludes, “Wildlife SOS, however, also assisted the Forest Department with radio-collaring of leopards to track their movement and range. Recently, the Maharashtra Forest Department collaborated with Wildlife SOS and Wildlife Conservation Society India (WCS-I) to radio collar three leopards in Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Mumbai. This is part of a project to study leopards and to help mitigate human-leopard conflict in the heavily populated urban landscape of Mumbai.”